Over the latter half of his career, Douglas Engelbart struggled to help organizations adopt augmented approaches to the technology that he had helped midwife in the 1960s. His Augmentation Research Center at the Stanford Research Institute focused on creating technology that would make us better, more creative, and more connected as human beings, but to the outside world he was merely “the inventor of the mouse.”

While innovations such as the mouse, the graphical user interface, and synchronous online work certainly humanized how we interacted with these new machines in profound ways, they did not change the social structures of work and innovation outlined in “Augmenting Human Intellect.” For a more detailed understanding of where he saw this effort go off the rails, see this video from 1998 (marking the 30th anniversary of the Mother of All Demos).

As I was attending the Smart Region Summit last week hosted by Arizona State University’s University Technology Office, I realized that this vision was taking shape more than half a century after Engelbart’s original work. The topics of discussion there ranged from broadband access to transportation to education in the Greater Phoenix region. The issues being addressed were not unique to Arizona. However, how they were being tackled was.

What the team at UTO has facilitated is conversations among communities that rarely interact during their normal course of business. New technologies of collaboration and discussion brought to maturity and widespread acceptance in part by the pandemic facilitated this melding of conversations that normally occur within silos. The fusion of ideas and projects that I saw last week was precisely what Engelbart had in mind as he wrote this in the 1990s.

An improvement community that puts special attention on how it can be dramatically more effective at solving important problems, boosting its collective IQ by employing better and better tools and practices in innovative ways, is a networked improvement community (NIC).

If you consider how quickly and dramatically the world is changing, and the increasing complexity and urgency of the problems we face in our communities, organizations, institutions, and planet, you can see that our most urgent task is to turn ICs into NICs.

The Smart Region group already laid the groundwork for this effort prior to the pandemic. From this foundation, the group successfully built upward, leveraging communities associated through geography. They could facilitate conversations about local, concrete challenges. It was the diversity of these conversations that technology fostered. Distributed collaboration technologies suddenly connected businesses, governments, and community groups that had never collaborated on this level before.

Over the past four years, another group within the UTO has also been attempting to create diverse, distributed communities. From the beginning, we conceived ShapingEDU as a different kind of educational community. However, ShapingEDU differs from the Smart Regions group in one key aspect: It lacks the geographic moorings of the latter group.

ShapingEDU’s strategic asset has always been its global, distributed design. The pandemic may have changed the substance of our efforts, but it did not alter our methods much. While we lost our annual in-person touchstones, most of our work and collaboration continued much as it had via technology platforms such as Zoom, Slack, and Google apps.

However, what is ShapingEDU’s greatest strength is also its greatest weakness. Localized concerns confronting community members often overwhelm the distributed efforts of the connected community. With any kind of distributed community, there is always the danger of it becoming disconnected from the immediate concerns and needs of its members. For communities concerned primarily with information distribution, this is manageable. However, for a community of doers, this presents a significant stumbling block.

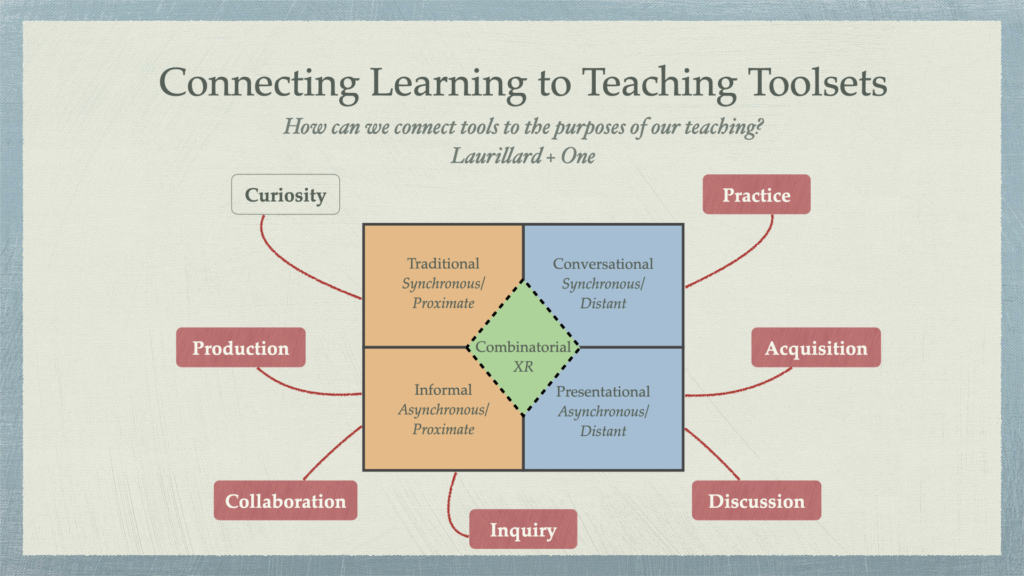

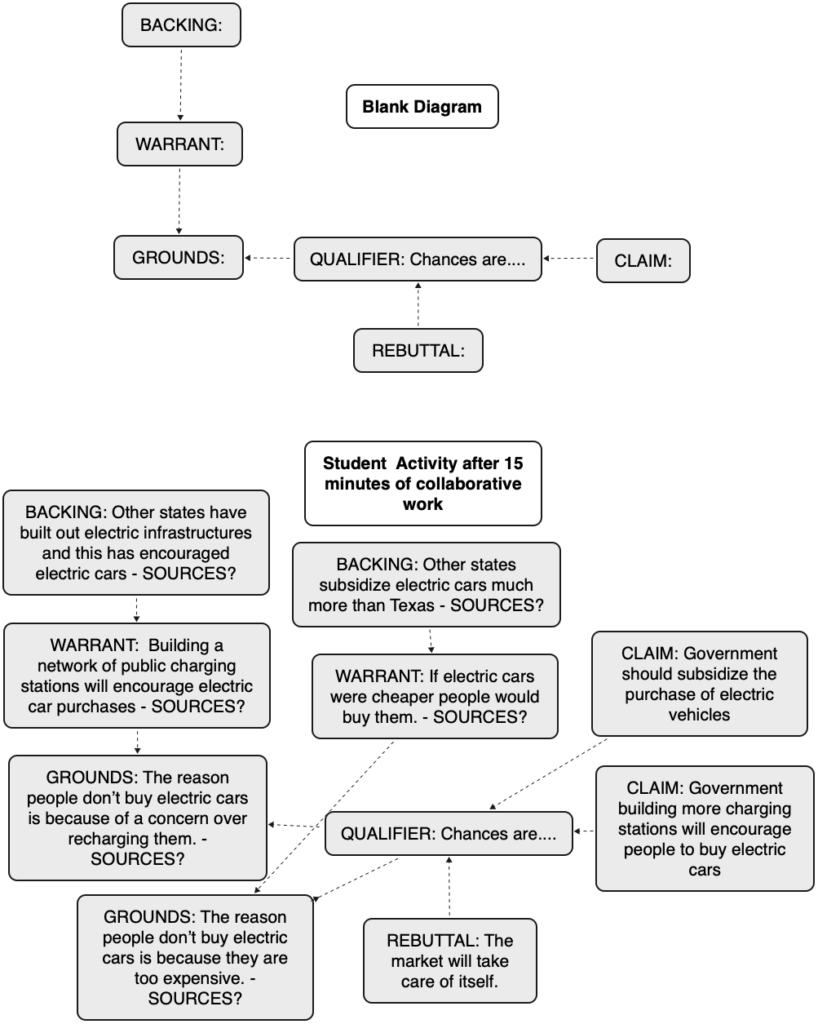

There is another analogy. As teachers, we encounter similar challenges if we attempt to turn remote classrooms into anything more than information distribution mechanisms. Keeping the students actively connected to the conversations in the class has proven to be a primary challenge, as we have experimented with remote teaching. As a teacher, I’m always trying to boost the “collective IQ” of my students.

As an organization, ShapingEDU has always tried to boost the “collective IQ” of its participants and the larger education community. One approach to this challenge of distributed connection would be to adapt the model of the Smart Region project to create nodes of connected network improvement communities. These nodes would be localized and connect diverse teams. This same approach could scale the Smart Region approach to other regions.

A connected series of nodes was the vision of the short-lived FOEcast group that many members of the ShapingEDU community were a part of in early 2018. We envisioned a “distributed university” connecting and assembling insights from groups working around the globe. The global organization would facilitate conversations, collect work, and act as a distribution platform for these geographically dispersed groups.

Practically, what this means is that the doing of the working groups must be profoundly local and that the efforts of the distributed group would to facilitate global dreaming into localized doing. This is something ShapingEDU’s Universal Broadband Project Team has excelled at. Groundbreaker Lisa Gustinelli has connected national resources to profoundly local needs in Belle Glade, FL, by bringing FCC resources to a local community desperately in need of better connectivity to thrive.

ShapingEDU has always mapped out a vision where the distributed imagination of the collective group generates impactful local action. This is only possible because of the tools that technology has developed for distributed and persistent engagement. However, as Engelbart understood, our human organizations need to be optimized to take maximum advantage of the opportunities that technology creates. ShapingEDU creates fora that stimulate creative play, offers practical guidance, and provides opportunities for congregation and the sharing of insights.

The vision that Doug Engelbart consistently articulated was that we should use technology to augment our capacity to be human. In this, he echoed Vannevar Bush’s vision of using technological affordances to connect communities of thinkers. It is only through these networks of ideas that we can hope to tackle the enormous problems that were the detritus of Industrial Age thinking.

Many of the challenges that the Smart Region team are trying to address have to do with community responses to Industrial Age challenges of sprawl, pollution, and equity. Education faces similar challenges that are a legacy of systems of Industrial Age thinking. We are struggling to adapt institutions and practices designed for elite education to foster diversity and equity.

Overcoming these barriers will require a diverse community of thinkers to support a vast network of doers tackling the shifting landscape of education unique to their circumstances. As William Gibson said, “The future is here. It’s just not evenly distributed.” Supporting unevenly distributed “presents” will require creating networked improvement communities committed to building their best “futures” through deep learning and reflection. A fusion of models might just get us there.