Originally Published on the ShapingEDU Blog on January 12. 2023

We must get lost before we can find ourselves. Maps should not concentrate on preventing us from getting lost. Instead, they should point us to new ways of finding our way. Expressions like “we navigate learning“ don’t come from nowhere.

When we learn, we explore the edges of what we understand, but we also explore our imaginations and what they’re capable of. I wrote about this extensively in Discovering Digital Humanity. However, my work on the Tool Augmentation Tool reinforced my perception of just how important a role mapmaking plays in the process of creativity, innovation, and learning.

I recently wrote about how tools map our brains. Those who use those maps are engaging their brains in exploration. The idea is to get the user lost in their imaginations and then have to find their way back again. I use maps extensively in my classroom instruction in much the same way, as I try to map out the semester to my students while giving them ample room for creative exploration.

Creative exploration, however, doesn’t always happen. Both students and the academic decision makers that I regularly work with start with the assumption that I’m going to provide them with a map that will navigate them to their destination.

My challenge as a teacher lies in guiding without prescribing. This creates tension as I struggle to show them how to grow their own insights instead of just adopting mine.

Cartographic scholar Alan M. MacEachern’s work offers some valuable insight into how to create maps (and, by extension, all other kinds of abstract visualization) as tools for the visual exploration of information. In 1990, MacEachern and John H. Ganter wrote that:

[T]here is an assumption not only that the message is known, but that there is an optimal map for each message, and that our objective as cartographers is to identify it. For cartographic visualization the message is unknown and, therefore, there is no optimal map. (p. 65 – emphasis in original)

All-too-often we perceive the “destination” as a known entity. One problem with our growing dependency on Google maps is that we have lost the ability to find our own way through a map creatively. Most of the time, it presents a series of turns that magically transport us to the end of your journeys.

However, Google is not perfect. It makes certain assumptions when it plots the “optimal” route for me. The problem is that Google doesn’t really know me. It doesn’t understand my preferences for the journey. Do I want the fastest route, or do I want to compromise that to make the journey more relaxing? Do I want to explore a road I’ve never traveled before? It can’t really answer these kinds of questions.

Our educational processes often mirror the shortcomings of Google Maps because they likewise ignore the sensemaking aspect of our journeys. Industrial education has produced increasing levels of specialization, coupled with processes that emphasize “learning” modules and tests. Like Google, it gives us a series of turns defined as “courses” and “degree plans” that navigate the student magically to a degree.

We extend prescriptive navigation into the microcosms of individual courses. The term “course” itself implies a singular pathway through the process. Our college journeys have become nothing more than sequences of turns, lacking in sensemaking or meaning. Both students and the systems that control their movement through their learning journeys resist efforts to create randomness in that process.

A map with a singular pathway toward a destination is not a map, it’s a course. Maps imply a level of exploration. They should help you understand the broader context of your journey. Otherwise, we will never see outside the tunnel of our path and will miss the larger picture of the world that maps abstract. MacEachern and Ganter imply this when they state,

Maps and other visual representations are valuable to science, not because of their realism, but because they are abstractions. The abstraction process, if successful, helps to distinguish pattern from noise. p. 66

It is hard to create maps that encourage exploration without creating prescriptive instructions. In my classes, I try to create maps that explicitly force the students to explore. Getting them to follow them into the unknown and unpredictable, however, is not so straightforward. Grades form an unwavering destination for all of them. All that matters is finding the shortest path there, not what you may discover along the way.

I have a similar problem when I try to create maps to help others integrate technology into their practice. Considering a problem is more difficult than simply “getting the answer.” When I was working for an architecture firm, they were intent on having me produce an “ideal” learning space. When I pointed out that learning spaces were environments that helped people self-actualize their learning, and, for that reason, there was no one-size-fits-all solution, they didn’t like that answer.

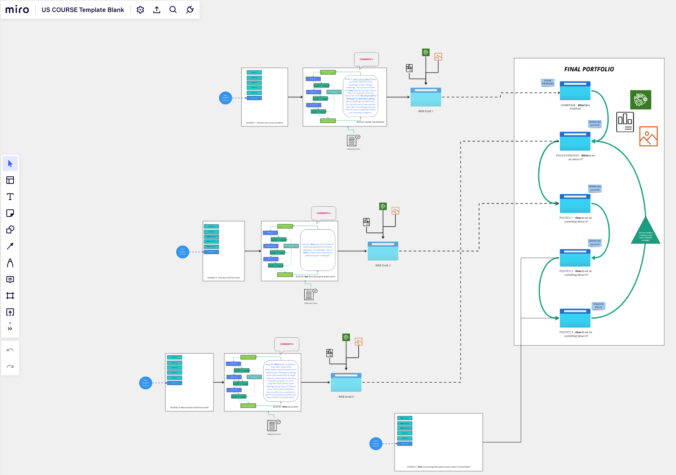

Learning spaces contain within them implicit maps. We can extend this to any technology or technology environment. The Tool Augmentation Tool is an attempt to construct a map to help us understand the landscapes we create as we design environments for learning and innovation. It shows a series of pathways through a maze, but at every juncture, the user must add external inputs that change the character of the pathways that are being traveled.

We must also create maps that preserve a role for the teacher. You can teach by careful map design, but you can also design maps where either the teacher or a group of peers teach while using the map as a tool. The collaborative aspect of mapmaking is central to my practice as a facilitator of learning. Using tools like Miro to create maps of ideas opens vast new possibilities for innovation.

The Tool Augmentation Tool sets up a system of systems that moves users from tool to task in a variety of ways. It forces them to view the map from the perspective of a synchronous activity, both in-person and distantly. This shift in perspective creates different mental maps of the impact a particular technology will have on practice. The exercise then asks the user to consider the same two modalities (in-person and distant) as a set of asynchronous experiences.

Finally, it requires that the user reconnect these distinct explorations to form either a tool recommendation or a deep understanding of how a tool will impact a task., “The system should permit, indeed perhaps demand, that the user experience data in a variety of nodes.” (MacEachern and Ganter, 1990, p. 78)

A good map should force the user to zoom in and out and change our perspective. It jostles our complacency with “accepted” data. There are no “best practices” in this world. There is no “dogma” other than a goal of human augmentation.

Technology has made mapmaking infinitely more accessible. Tools like Miro have made interactive explorations of connective spaces possible in ways that were impossible even a few years ago. Building collaborative maps helps us find our humanity and make sense of a complex world of interconnections.

Sensemaking is the core of learning at all levels. It represents an intensely personal journey. We have a duty to help each other navigate that path but should not dictate it for others. Synchronous collaborative mapmaking makes it possible to journey together without giving up our individuality along the way. We are all designing the map of the future. Without collaboration and exploration, this would be an impossible task.