Over the last 40 years of my education as a technologist I find myself returning to some of the same texts over and over. As I have taught workshops over the years, I’m sometimes amazed how unfamiliar people are with some of these texts even as they try to implement technology solutions either as IT practitioners or users of technology. Technology fails because we don’t think deeply about what we’re doing before trying to graft a “solution” onto a problem we don’t really understand. These books are designed to make you think differently about how you apply technology.

There are lot of overlaps between various books and no book fits cleanly within a specific topic area (and there are some topic areas that blend two areas). However, I will be dividing this list into 7 “Chapters”: Designing Technology, Designing Systems, Understanding Systems, Applied Technology – Network Design, Applied Technology – Narrative Design, Applied Technology – Human Design, and Designing New Realities. I started mapping these as a concept map but then, 2/3 of the way through the process, I recognized that a Venn diagram was a better representation of the blended web of ideas that these 25 titles represent.

Part I: Designing Technology

These books deal with the concepts that shape or shaped the design of technology.

– 1 –

|

|||

Designing Technology |

Rheingold, along with Steward Brand and Kevin Kelly, are the storytellers of the computer era. Brand is particularly attuned to the intersection between how we share ideas and the possibilities of the new technology. This volume is a very accessible overview and history of the first 175 years of the computing revolution (it starts with Babbage and Lovelace).

He introduces us to a cast of characters that come from the “softer” side of the technology revolution. In many cases they were instrumental in inventing key technologies but, more importantly, thought deeply about what to do with it. These were the people who set the technical goalposts for the engineers to build toward. The people he profiles in this book are the reason we have accessible technology at all instead of still living in a world of punchcards and mainframes. We will meet many of these characters again and again in this series of books. Their ideas are evergreen. They are not concerned with technology. They are concerned with enabling the human in us to create, learn, and grow. Why This Book Matters In My Work: This is the part of technology history that so often gets ignored. It is not about the machines. It is about the imagination of those who conceived of the machines and the unexpected uses those machines were put to through the imaginations of others. All technological creations need to begin and end with how they augment us and others. The purpose of the IdeaSpaces framework is to provide a roadmap to this kind of thinking. |

||

Key Quotes“The human mind is not going to be replaced by a machine, at least not in the foreseeable future, but there is little doubt that the worldwide availability of fantasy amplifiers, intellectual toolkits, and interactive electronic communities will change the way people think, learn, and communicate.” “Ted Nelson is voicing what a few people have known for a while from the technical side – that the intersection of communication and computer technologies will create a new communication medium with great possibilities. But he notes that the art of showing us those possibilities might belong to a different breed of thinker, people with different kinds of motivations and skills than the people that invented the technology.” |

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):Fisher, Adam, Valley of Genius (Twelve Books, 2018) – an oral history of Silicon Valley Waldrop, Mitchell, The Dream Machine (Viking, 2001) – the computer age through the eyes of one of its architects, J.C.R. Licklider |

|||

– 2 –

|

|||

Designing Technology |

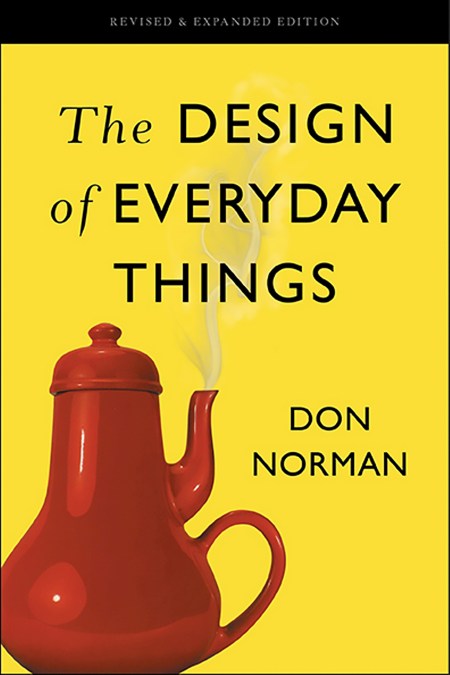

The principles that Norman explains his seminal book seem so obvious that it constantly amazes me how much we ignore them as we build and design things. The book is so much more than human-machine interaction. It’s also about human-human interactions and how our design of machines impacts that. At its root, it’s this humanity that characterizes Norman’s perception of the challenges of design.

As we constantly wring our hands over our impending machine overlords, this book serves as a powerful reminder that we design the technologies that we interact with every day. As technology becomes ever more removed from end user understanding, these processes of design become even more important. A carpenter would never accept a hammer that made hammering more difficult. Yet, we constantly accept technologies that are designed so poorly that they make even everyday tasks more challenging than they need to be. Norman gets to the root of this very human problem. Why This Book Matters In My Work: Norman reminds us that it’s the small things that matter. As I have designed learning spaces and technology systems over the years, I have often learned the hard way that messing up the tiniest detail of SPACE attracts disproportionate attention. These small oversights often become the focus of resistance to the positive change I was trying to build and can undermine an otherwise carefully-designed project. For want of a nail… |

||

Key Quotes“Engineers are trained to think logically. As a result, they come to believe that all people must think this way, and they design their machines accordingly… The problem with the designs of most engineers is that they are too logical. We have to accept human behavior the way it is, not the way we would wish it to be.” “Technology changes rapidly, people and culture change slow.” |

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):Lorber, Azriel, Misguided Weapons: Technological Failure and Surprise on the Battlefield (Brassey’s, 2002) – Conflict is a crucible of all design. Failure is measured in death and defeat. Failure to design technology and systems as well as to understand their proper application litters the battlefields of history. |

|||

– 3 –

|

|||

Designing Technology |

This seems like an odd book to include on a list for technologists. However, it is precisely in technology design where the kind of imaginative leaps that science fiction gives us can be applied most directly. There are clear connections between the Star Trek PADD and Apple’s iPad or between Star Trek’s communicator and the Motorola StarTek flip phone.

Science fiction offers an infinite canvas for technology design because the stuff on a film set doesn’t have to actually work. As this book demonstrates, often these ideas turn out to totally impractical or very unergonomic (such as the famous gesture interface from Minority Report). However, every so often, an engineer or designer will become inspired by something they see on screen and work out how to make it real, as in the aforementioned examples. At the very least, this book will result in some creative mind-stretching. At the most, it teaches all of us to look outside our “disciplines” for inspiration for that is where the truly creative ideas will come. Why This Book Matters in My Work: Speculative fiction helps me stretch my thinking of what is possible with a given technology. It teaches me not to accept what I’m given but rather to dream about what is possible. IdeaSpaces is about constructing realities. Sometimes it’s helpful to have models. |

||

Key Quotes“We’ve seen repeatedly that if an interface works for an audience, there’s something there that will work for users. Finding what that thing is and using it for inspiration in our own work is part of how we can use these speculative interfaces.” “It’s science fiction as an estranging design tool, a conceptual approach, best suited for blue-sky brainstorming, for calling the everyday into question, and for making the exotic seem practical.” |

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):Munroe, Randall – Thing Explainer: Complicated Stuff in Simple Words (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015) – Another kind of design book. Explain everything using the 1000 most common words in the English language. Makes you think hard about complexity as you design things. |

|||

– 4 –

|

|||

Designing Technology |

How Buildings Learn is a book about architecture written by a technologist and that simple fact alone makes it a book worth reading. The fact that that technologist is Stewart Brand, the creator of the Whole Earth Catalog and chronicler of the computer age, ensures that this is will be a unique exploration of a venerable topic. It amazes me how few architects are aware of this book. It also amazes me that people don’t realize that this is a technology book.

Brand, who had been intimately tied into the computer revolution for over a quarter century when he wrote this book, recognizes in buildings, something we take for granted, an essential technology that is not immutable. As I design technology spaces and learning spaces, this book has never been far out of reach. Most notably, its message that the end of the “building” process is just the beginning of a whole new process of adaptation has led me to design spaces that are fluid and adaptable for their users and inhabitants. Why This Book Matters in My Work: This book has badly corrupted my thinking about space design. When we build stuff, we like to admire it once it is complete. It is a basic human trait. For things like my photography, I like to think that once I’ve polished it, it is finished. However, even there the SPACE I’ve created is subject to interpretation and reinterpretation by viewers. Anything that people can physically manipulate will be changed even more. This book taught me to build sandboxes for others, not monuments to myself. (Unfortunately, we live in a world where people only look at monuments.) |

||

Key Quotes“Between the world and our idea of the world is a fascinating kink. Architecture, we imagine, is permanent. And so our buildings thwart us. Because they discount time, they misuse time.” “The word ‘building’ contains the double reality. It means both “the action of the verb BUILD” and “that which is built” — both verb and noun, both the action and the result. Whereas ‘architecture’ may strive to be permanent, a ‘building’ is always building and rebuilding. The idea is crystalline, the fact fluid. Could the idea be revised to match the fact?” “The transition from image architecture to process architecture is a leap from the certainties of controllable things in space to the self-organizing complexities of an endlessly raveling and unraveling skein of relationships over time. Buildings have lives of their own.” |

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):

|

|||

Part II: Designing Systems

These books are about coupling design with technology to reshape our human systems.

– 5 –

|

|||

Design |

Pendleton-Jullian and Brown have authored a seminal volume on how we think about the world and how in a technological world everything is subject to design. Moreover, they also argue that we have an imperative to engage in emergent design as we approach the complex problems that our technological world confronts us with.

This first volume provides an expansive view of the design process. The second volume provides us with a set of case studies and practical models for application. Both books provide an incredibly rich stew of insights and ideas that inform just about everything I build, from actual buildings to course designs to organizational models. Take your time with this one. I found that each chapter requires at least a week of reflection to adequately digest what’s contained in it. I return to these books time and again. The books themselves are fascinating explorations of nonlinear design in a linear medium. They are only available as a print version because, I assume, the authors recognized that providing versions in multiple media would compromise the storytelling they are attempting to achieve. These books are not “books” per se. They are experiences. They will change how you think about applying technology in a world shaped and driven by technology. Why This Book Matters In My Work: What the Brand book did for my thinking on SPACE, this book did for my thinking on TIME and STRUCTURE (as well as SPACE). There are so many ways that this work has influenced my thinking about designing everything from physical (and virtual) artifacts to organizations. Emergent Design, like Brand’s view of buildings, recognizes that everything is a work in progress but that we can still apply sensible design processes to the moving train that is our lives and work. |

||

Key Quotes“We all recognize that we are in a unique moment in our evolution because of the exponential increase in information and interconnectivity of everything around us, and the very real human responses to these. It is a Cambrian moment of profound change as we move from understanding static societal building blocks to flows of exchanges, from rigid organizational structures to dynamic networked relationships, from thinking systems to thinking ecosystems.”

|

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):Raworth, Kate, Doughnut Economics: 7 Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist (Chelsea Green, 2017). – The Doughnut is a constructivist approach to thinking about capitalism that aligns well with the principles of Design Unbound. |

|||

– 6 –

|

|||

Design |

If I had one book to suggest to any non-technical leader who needs to understand the possibilities and limits of technology, it would be Intertwingled. I’ve given a copy to more than one boss of mine over the years. Morville masterfully “intertwingles” practical advice with deep thinking about how technology works. This book was an inspiration to my own book, although I could not hope to match its elegant simplicity. Morville is an information architect who has deeply integrated the thinking of both Ted Nelson and Douglas Engelbart into his own thinking of how we build technology systems. While he is mainly talking about software implementations, the same logic can be applied to any technology application. As we will see from other books on this list, technology is software for the human condition. If we understand how software/technology and human culture intertwingle, we can begin to understand how to implement technology to augment humans. This is the lesson of Intertwingled. Why This Book Matters in My Work: The job of a technologist is not to change technology, it is help humans to think and build. Morville’s book is a great primer for those who need to think about technology but who aren’t technologists. This is the book I’ve given away most frequently to non-technical decision makers. Without going into detail on the history that Rheingold does, Morville boils down the basic ideas that the thinkers in Tools for Thought worked through into digestible, applicable bits. |

||

Key Quotes“Code is a function of culture…. It’s not that the tail can’t ever wag the dog, but when it does, it usually happens quite slowly. That’s why I balance my specialist focus on the information system with a generalist’s eye toward the wider ecosystem. Information architecture is an intervention. It disturbs an established system. To make change that lasts, we must look for the levers and find the right fit. If we fight culture, it will fight back and usually win. But if we look deeper, and if we’re open to changing ourselves, we may see how culture can help.”

|

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):

|

|||

– 7 –

|

|||

History |

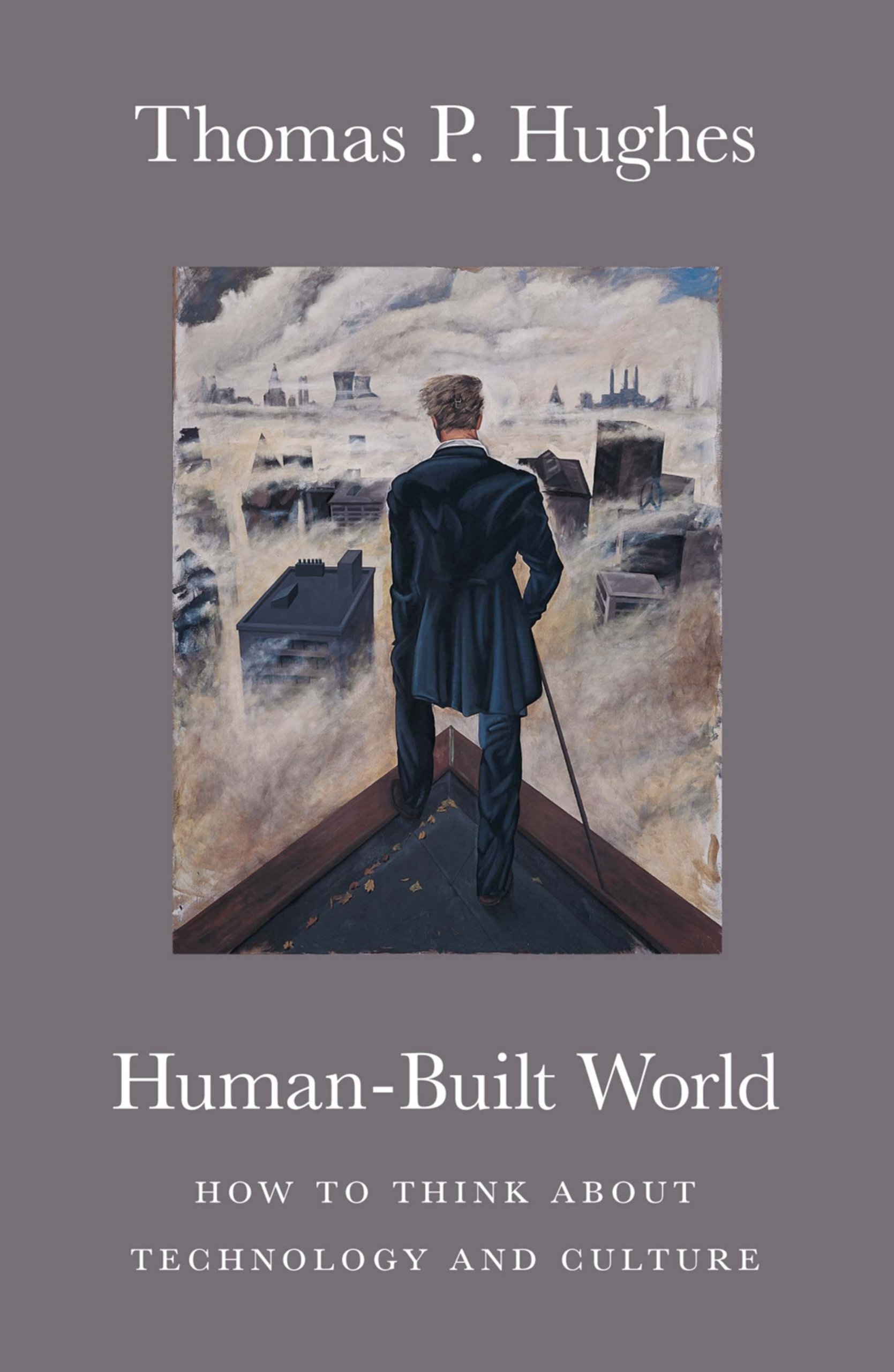

It takes perspective to understand that we live in a socially-constructed world. This world is intimately bound up in our relationship with our technological systems and the social structures we construct around them. Hughes provides a short but deep review of how this relationship between humans and technology has been interpreted and re-interpreted over the centuries.

If anything, the computer should be the ultimate expression of how we can adapt and change technology to suit our needs and yet we don’t take advantage of what is possible with it. As a social scientist with a long appreciation of the power of constructivism in both my theory and practice, this relationship is central to my appreciation of the possible. Hughes shows how we can be convinced to accept the unacceptable but that this is our choice. We can also reshape anything and everything to build a different future that is built around the human. Why This Book Matters to My Work: As a student of constructed history, I’ve long recognized that we build worlds to make sense of the world around us. It stands to reason that, as technology has taken on a greater portion of our existences, that we should try to make logical patterns to try to understand and contextualize how it has reshaped our lives and society. We take many of these STRUCTURES for granted and don’t recognize how we design technologies that either support or undermine them. IdeaSpaces spans the spectrum from the technology (SPACES) to STRUCTURES we build around them (including TIME) because of this kind of thinking. |

||

Key Quotes“A technologically literate public might reject technological determinism and accept the current social science argument that technology is malleable and subject to social control. In recent years historians and sociologists have provided many examples of socially-constructed technology, the opposite of technological determinism. By socially-constructed, they mean that the public, through organizations and individuals, can make choices about the characteristics of the technology they use and and the effects it will have upon them.”

|

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):Bijker, Wiebe E., Thomas P. Hughes, and Trevor Pinch eds., The Social Construction of Technological Systems: New Directions in the Sociology and History of Technology (MIT Press, 2012) – an edited volume of articles about the social construction of our technological and human spaces McCrossen, Alexis, Marking Modern Times: A History of Clocks, Watches, and other Timekeepers of American Life (University of Chicago Press, 2013). – how we constructed our modern notions of time during the industrial era Shlain, Leonard, Art and Physics (Morrow, 1991) – an exploration of how art and physics have co-evolved over the centuries as we try to depict our world as we can imagine it while imagining our world as we depict it Wilford, John Noble, The Mapmakers: The Story of the Great Pioneers in Cartography from Antiquity to the Space Age (Vintage, 1982) – Wilford presents a masterful account of how our paradigms of the world shifted as we learned to chart it. We need to learn from explorers who felt their way across the globe with primitive measurement instruments and made charts that told those back home what the new worlds looked like. |

|||

– 8 –

|

|||

Information Studies |

With his short paper and subsequent book, Claude Shannon created the digital world. He did this by the expedient of showing how all communication could be broken down into a simple binary code.

Shannon was solving a very distinct problem of being able to accurately transmit information through a wide variety of means and to cut down on the errors he was getting in transmission. The brilliant insight that he fell upon drew on his work on both sides of the cryptography problem during World War II: we “waste” a lot of information in general communication. With enough redundant data, you can overcome the inevitable transmission errors. However, the systemic shock he set in motion was that it really didn’t matter how this data was assembled and reassembled as long as you provide information with certain markers and redundancy. After Shannon, information no longer needed to be linear. After Shannon, we could assemble and reassemble digital worlds into an infinite variety of possibilities. Over 70 years after its publication, we continue to struggle with Shannon’s basic insight as we seek to liberate our thinking from the shackles of analog/industrial thinking. Warren Weaver does a great job of humanizing the challenging theorems that Shannon presented in his original 1948 essay. However, if you want even more context, read the excellent biography of Shannon, A Mind at Play. Why This Book Matters to My Work: The idea that everything can be reduced to digital bits and be infinitely recombined is something that most people have trouble grokking. If you are in the business of building sandboxes for creative activity, which is the core of what every technologist should be doing, you have to be one of those people. |

||

Key Quotes“The word communication will be used here in a very broad sense to include all of the procedures by which one mind may affect another. This, of course, involves not only written and oral speech, but also music, the pictorial arts, the theatre, the ballet, and in fact all human behavior.”

“Thus we can approximate a coding system to encode messages from this source into binary digits with an average of binary digit per symbol. In this case we can actually achieve the limiting value by the following code (obtained by the method of the second proof of Theorem 9): A 0 B 10 C 110 D 111”

|

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):Soni, Jimmy and Rob Goodman, A Mind at Play: How Claude Shannon Invented the Information Age (Simon & Schuster, 2017) – puts Shannon’s work into context with both his larger career as well as the world around him. |

|||

Part III: Understanding Systems

Technology doesn’t operate in a vacuum. These books are all about how systems adapt, resist, and can be shaped by the humans that inhabit them.

– 9 –

|

|||

Systems Thinking |

I was first introduced to Thomas Kuhn as an undergraduate through his earlier book, The Copernican Revolution in a History of Science class. The concept that ideas could develop into systems of thought that shaped what we would accept and wouldn’t accept despite increasing evidence that we were wrong fascinated me. That book was about the century-long struggle from Copernicus to Newton to redefine cosmology. As technologists we often like to think of technology driving change. That is a false notion. Humans drive and resist change even in the face of overwhelming evidence.

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions is a systematic analysis of the topic that Kuhn first explored in his earlier book. He establishes the concept of paradigms, systems of thought that dominate the perceptions of the mass of people within a society, group, or organization. Over the remainder of his life, he continued to explore and expand on this concept. Paradigms are the toughest systemic resistance to change to crack (see the next title on the list). We like to think of science as being driven by expansions in our ability to observe nature but even here biases and systemic structures can get in the way of understanding what we are seeing. Translated onto the social science stage, this problem becomes much worse because the phenomena there are highly subject to interpretation (does strength deter war or encourage it?). But even at an organizational level, these struggles can become a real problem for technologists. Some technologies should bring into question the very structure of how organizations operate but they don’t because they run up against institutional paradigms. “This is how we’ve always done classes.” “Employees need to be here from 9 to 5.” It is only when we understand these realities that we can begin to confront how they limit what we can achieve. Why This Book Matters to My Work: I am constantly bashing my head up against systems. When I first read this book during grad school, I thought of systems in the abstract but they are very real and concrete things. I used the word “STRUCTURE” in the IdeaSpaces framework to refer to the systemic level of technology design but systems are everywhere. Kuhn showed me that systems are malleable and not immutable and this informs the dynamic nature – at all levels – of the IdeaSpaces framework. |

||

Key Quotes“Practicing in different worlds, the two groups of scientists see different things when they look from the same point in the same direction.”

“Because the unit of scientific achievement is the solved problem and the because the group knows well which problems have already been solved, few scientists will easily be persuaded to adopt a viewpoint that again opens to question many problems that had previously been solved. Nature itself must first undermine professional security by making prior achievements seem problematic. Furthermore, even when that has occurred and new candidate for paradigm has been evoked, scientists will be reluctant to embrace it unless unless convinced that two all-important conditions are being met. First, the new candidate must seem to resolve some outstanding and generally-recognized problem that can be met in no other way. Second, the new paradigm must promise to preserve a relatively large part of the concrete problem-solving ability that accrued to science through its predecessors.”

|

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):Kuhn, Thomas S., The Road Since Structure (University of Chicago Press, 2000) – Kuhn updates and reflects back on the thinking he started with The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

|

|||

– 10 –

|

|||

Systems Thinking |

If we understand that the complex modern world is made up of a myriad of interconnected systems, we have to understand what happens when we challenge those systems. Technology challenges paradigms like the natural world described in Kuhn’s book. The key difference is that technology is a human-driven project. It may be driven by the logic of change but that doesn’t mean that systems/paradigms will change easily when challenged by new ways of doing things.

Meadows realized that our human systems we profoundly out of synch with the realities of our planet through her groundbreaking work in the 1960s and 70s which produced the “Limits to Growth” study that showed how our industrial policies were polluting the planet and how far that could go before we destroyed civilization. After this, Meadows was disillusioned by the impact of the report and spent much of the remainder of her life trying to understand the systems that prevented change in the face of clear, scientific evidence. In this book, she explores her 12 Leverage Points, which she used to understand the inflection points in any system and what takes to change those. Every technology challenges systems and understanding what kinds of resistance you are like to face from the established “way of doing things” is an essential tool for every technologist. Why This Book Matters to My Work: While Kuhn showed me that systems are malleable, he did not give me a good roadmap for attempting systemic change. I understood why technology projects failed when they ran up against systemic challenges. I did not understand a strategy for navigating systemic change. This is what Meadows gave me. IdeaSpaces is about facilitating change at all levels. Without being able to move STRUCTURES, it will likely fail or at least be very limited in its impact. Leverage points give me a roadmap for finding a way through the thicket of established beliefs and practices. |

||

Key Quotes“Social systems are the external manifestations of cultural thinking patterns and of profound human needs, emotions, strengths, and weaknesses. Changing them is not as simple as saying ‘now all change” or of trusting that he who knows the good shall do the good.”

“It’s easier, more effective, and usually much cheaper to design policies that change depending on the state of the system. Especially where are great uncertainties, the policies not only contain feedback loops, but meta-feedback loops – loops that alter, correct, and expand loops. These are policies that design learning into the management process.”

|

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):Senge, Peter M., The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of the The Learning Organization (Doubleday, 1990) – how systems respond to challenges is a central point this book from a colleague of Donella Meadows

|

|||

– 11 –

|

|||

Systems Thinking |

As technologists, we are designers of systems, and I’m speaking much more broadly here than networks of computers. Technology systems form part of much larger systems of human behavior and are subsumed, adapted, and change those systems. However, unexpected shocks can undermine them. Not all systems respond the same way to “black swan” events. We can design them to become “antifragile” and this is the subject of Taleb’s book.

Digital technology, in particular, has the capacity to create systems that grow from adversity but they have to be carefully designed to do so. For this reason, Taleb’s book is essential reading for any technologist. Imagine a world where suddenly everyone is forced to isolate due to a pandemic. How do you teach, learn, do business, etc. under those circumstances? As I discuss in Learn at Your Own Risk, my class thrived during the unexpected onset of remote teaching in the Spring of 2020 because of antifragile design. Why This Book Matters to My Work: Rigid systems crack when confronted with Black Swans just like rigid structures break when buffeted by wind or earthquakes. When designing systems to support technology or technology systems to support humans, they must be “antifragile.” Every system I design these days incorporates the thinking of Taleb as a cautionary tale that we can never really predict the future. We must design systems that allow humans to thrive in times of adversity.

|

||

Key Quotes“Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk, and uncertainty. Yet, in spite of the ubiquity of the phenomenon, there is no word for the exact opposite of fragile. Let us call it antifragile. Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better.” |

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):Taleb, Nassim Nicholas., The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (Random House, 2007, 2010) – How do systems react when they are challenged by unexpected shocks – not in the ways you’d expect

|

|||

– 12 –

|

|||

Systems Thinking |

I have a deep love for military history, particularly military history that shows humans and human systems adapting to technological change. Few institutions had to adapt to more rapid technological changes than navies in the period from the late 1800s to World War II. The US Navy was no exception.

Hone describes how the US Navy avoided some of the traps that other navies, particularly The Imperial Japanese Navy, fell into. We like to think of technological war in terms of guns, speed, and courage. Hone shows pretty convincingly that war is essentially about managing information about all of those things. The US Navy won the information space in World War II. This allowed it to learn, adapt, and build technologies that reflected the realities of combat in the Pacific. Hone describes systems that evolved into systems that fundamentally integrated change and feedback like Meadows describes into its fundamental matrix before and during the war. People like to argue that the loss of the battleships at Pearl Harbor in December 1941 forced the US Navy to adapt on the fly to a war centered around AirPower and smaller ships. Hone points out that the US Navy as an organization had already planned to fight this way because it had innovated in the 1920s and 30s to the point where battleships only formed a small part of the overall plan. The US Navy in 1942-43 developed into an antifragile system. Why This Book Matters to My Work: What’s a military history book doing on this list (and it’s not the only one)? This is a fascinating study of how systems adapt (or don’t) when confronted with rapid technological change. The technological changes that the US Navy had to adapt to in a little over 40 years (within the span of one career) are mind-boggling. Many of the organizations I work with are facing similar challenges. Look at the shifts in the information environment over the last 40 years and how organizations (business, education, and government) have adapted (or not) and you will start to understand how this example is so important to much of the work I do as a technologist. |

||

Key Quotes“A CAS [Complex Adaptive System] approach also embraces the inherent diversity of human systems, making it ideal for understanding the varied ways the Navy transformed into an innovative learning organization in the early years of the twentieth century. As Jean G. Boulton, Peter M. Allen, and Cliff Bowman have described, ‘Systems thinking deals with stable patterns and history deals with the particularity of events, conditions, and individuals—but complexity thinking marries the two and provides us with a sophisticated and unique theory of change. . . . It is detail and variation coupled with interconnection that provide the fuel for innovation, evolution, change, and learning.’” “Safe-to-fail mechanisms, in contrast, do not rely on assumptions about the future. Instead, they leverage redundancy, flexibility, and dynamic responses. Like a raft moving through rapids in a river—the rubber hull bending as it flows around the rocks—safe-to-fail systems absorb failure, continue functioning, and even thrive. They are far more effective at responding to stress in unpredictable environments.” |

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):Kuehn, John T., Agents of Innovation: The General Board and the Design of the Fleet that Defeated the Japanese Navy (Naval Institute Press, 2008) – a look at the decision making systems that created the US Navy of World War II |

|||

Part IV: Applied Technology – Network Design

At its root, the digital revolution is about communication. As Shannon demonstrated, you can shape anything if it can be broken down into digital bits. How we create networks of ideas and innovation are no different. Human systems require human networks. Technology design should build networks of ideas and turn them into something useful. In order to do this, all technologists should understand how these networks work and how technology can facilitate them.

– 13 –

|

|||

Human Networks |

This book has always been an inspiration to me as I design technological learning and innovation spaces, whether online or in a physical environment. It also provides critical insights in how networks of humans should be set up to facilitate change. The book contains two insights. First, the “slow hunch” concept is that innovation and ideas take time to gestate (no “eureka moment”). The second is his typology of networks.

Johnson identifies three kinds of networks: aerial – where ideas float freely but never go anywhere because they don’t find purchase; solid – where everything is frozen and new ideas never get get started; and liquid- where ideas can explore but are channelled in productive directions. In all cases, SPACES must create opportunities for liquid human networks to form so that humans have the TIME to nurture what Johnson refers to as “slow hunches” with other humans. As technologists we must always be looking for ways to use technology to create liquid networks, either through SPACE design or innovative uses of technology to channel and archive good ideas to let them evolve through slow hunches. Can we use technology to slow things down? Why This Book Matters to My Work: This book was seminal in my development of the Ideaspaces concept. Everything in Time-Space-Structure is oriented toward the creation of liquid networks. Understanding how humans come together to learn from another is critical for human-centered technology design. Johnson gives us a very accessible account of how that happens and how technology has facilitated or hampered human progress in the process.

|

||

Key Quotes“In a gas, chaos rules; new configurations are possible, but they are constantly being disrupted and torn apart by the volatile nature of the environment. In a solid, the opposite happens, the patterns have stability, but they are incapable of change. But a liquid network creates a more promising environment for the system to explore the adjacent possible.” “This is not the wisdom of the crowd, but the wisdom of someone in the crowd. It’s not that the network itself is smart; its that the individuals get smarter because they’re connected to the network.” |

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):Johansson, Frans, The Medici Effect: What Elephants and Epidemics Can Teach Us About Innovation (Harvard Business Press, 2004) – Innovation happens in the margins and it’s essential to construct your network of diverse groups of people to create environments for truly groundbreaking insight. |

|||

– 14 –

|

|||

Human Networks |

Naughton provides us with the long view when it comes to development of our information networks. He points out that it took decades for Gutenberg’s revolution to shift the cultural landscape and that we are just at the beginning of that process for the internet.

This book points out the ways that the information environment we are experiencing now is cracking norms but that we need to understand how it works in a broader perspective. Networks are human, not technology. Naughton’s metaphor of our information spaces as evolutionary ecosystems is an important insight as we design the networks that will drive society going forward. Why This Book Matters to My Work: Naughton really helped me see our information environments as complex ecosystems. I used this insight into creating learning and collaboration environments to facilitate complex information ecosystems that fuse multiple and wide-ranging networks of information together into an innovative whole. |

||

Key Quotes“In science, an ecosystem is ‘ a community of plants, animals and micro-organisms, along with their environment, that function together as a unit.’ In those terms, a media ecosystem can be seen as a community of organizations, publishers, authors, end users and audiences, along with their environment, that function together as a unit.” “A central argument of this book is that the Internet is best understood as a global system for springing surprises or – to put it more politely – a system for enabling disruptive innovation.“ |

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):Jarvis, Jeff, Gutenberg the Geek (Amazon, Kindle Single, 2012) – An analysis of Gutenberg as an information entrepreneur and his influence on Silicon Valley Shirkey, Clay, Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age (Penguin Press, 2010) – How media reshapes our ability to collaborate as a society. |

|||

– 15 –

|

|||

Human Networks |

The more things change, the more they stay the same. Standage’s excellent exploration of how media and society have interacted since Roman times is essential reading for anyone designing systems for exchanging information. He consistently points out that what we are used to, which he calls the “mass media parenthesis” is actually very much an exception to the norm of how we communicate as societies.

He also concludes that efforts to control information are increasingly difficult in a digital world. In the pre-mass media world, there were significant technical challenges for true mass distribution of information, not the least of which was illiteracy. These technical challenges lowered themselves somewhat during the industrial era but but in doing so concentrated distribution mechanisms in the hands of the few. The digital age is returning us to the earlier paradigm, he argues, with much higher levels of literacy and tools for visual communication to enhance the network effect. My local school district locks down access to range of information sources through their school networks instead of investing in digital literacy programs. The predictable response is that my kids now know more about Virtual Private Networks and how to use them to circumvent firewalls than I do. Standage constantly reminds me that it may look like the world has changed, but humans have not. We find ways to construct familiar networks, whether they are in the town tavern or on Facebook. If we design technology for human advancement and not for the sake of “change,” we can create evergreen, approachable information systems. If we don’t, they will likely fail. Why This Book Matters to My Work: I am always mindful of these realities as I design technological STRUCTURES for information distribution. When I create physical SPACES, I always design them with human networks in mind. When I look at systems of social media, I am always mindful that, while they might change how TIME works, they reflect persistent STRUCTURES of human networks. Therefore, I am always biased toward more transparency and less control. Standage rightly points out that most of the evils of our communication systems come from those who seek to control the technology for their own benefit. As technologists, it is our responsibility to disrupt those systems of control for the benefit of humans. |

||

Key Quotes“In many respects twenty-first century Internet media has more in common with seventeenth-century pamphlets or eighteenth-century coffeehouses than with nineteenth-century newspapers or twentieth-century radio and television. New media is very different from old media, in short, but has much in common with ‘really old’ media. The intervening old-media era was a temporary state of affairs, rather than the natural order of things.” “Those in authority always squawk, it seems, when access to publishing is broadened. Greater freedom of expression, as John Milton noted in Areopagitica, means that bad ideas will proliferate, but it also means that bad ideas are more likely to be challenged. Better to provide an outlet for bigotry and prejudice, so they can be argued against and addressed, than to pretend such views, and the people who hold them, do not exist. In a world where almost anyone can publish his or her views, the alternative, which is to restrict freedom of expression, is surely worse.” |

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):

|

|||

– 16 –

|

|||

Human Networks |

McNeely and Wolverton provide us with a wonderful history of how our networks of knowledge have been constructed and reconstructed over the last 2000 years. Like Standage, they point out similarities between the information environment of today and those of hundreds of years ago.

One of the most fascinating chapters is the one on The Republic of Letters, a network of letter writing between scholars in the 17th and 18th centuries that powered the Enlightenment. The reason this is so relevant to the information SYSTEMS I try to facilitate today with technology is that it is a powerful example of a nodal, decentralized network connected by technology. Today’s larger companies and educational institutions are rarely all located in the same geographic space. Even smaller information environments are deeply interconnected with partners across cities, states, countries, and the globe. As technologists designing systems for supporting diverse, complex environments, I must understand how they function on a basic human level before aligning the right technology strategies with them. As McNeely and Wolverton (as well as all of the other books in this section) point out, information environments that are not diverse quickly stagnate and do not support learning and innovation. Understanding what has worked and what hasn’t as we have sought to “reinvent knowledge” over the centuries is crucial if we want to design effective information-exchange systems. This understanding make emergent knowledge design possible. Why This Book Matters to My Work: I am constantly looking for opportunities to construct what Douglas Engelbart describes as Networked Improvement Communities. This book provides me with numerous historical examples of how this has worked in practice. These are complex systems that seek to scale, distribute, and augment local innovation efforts. We have lots of technologies that can help us construct these kinds of STRUCTURES. Understanding how to put these together is the job of the technologist. |

||

Key Quotes“[T]he earliest universities, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries – at Bologna and Paris – were not deliberately founded; they simply coalesced spontaneously around networks of students and teachers, as nodes at the thickest points in these networks.” “Its history raises the question raises the question of why Europe’s diversity brought progress in scholarship when by rights disunity ought to have crippled it. The answer is as simple as it is radical: with existing institutions of learning in crisis or collapse, the Republic of Letters founded its legitimacy on the production of new knowledge. Real bricks-and-mortar institutions – print shops, museums, and learned academies – provided it with substance, as we will see. The Republic of Letters acted as an umbrella institution for them all. Owing to its legacy, international cooperation remains a hallmark of Western scholarship to this day.” |

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):

|

|||

Part V: Applied Technology – Narrative Design

Everything we do revolves around telling stories. We tell stories to ourselves to make sense of the world. We tell stories to others to share their sense of the world. Digital Technology has changed our ability to tell and consume stories perhaps more than any other facet of our lives. An entire section of Discovering Digital Humanity is all about how the Digital Age reshapes our narratives. While the stories themselves haven’t changed, the ways we can tell and design them have. These books explore that idea.

– 17 –

|

|||

Narrative Design |

Our relationship with text is a technologically-mediated one. This relationship fundamentally changed with the invention of word processing in the 1970s. That is the central premise of Matt Kirschenbaum’s Track Changes. What we write is dictated in part by how we write.

The first book in the Designing Media section is about how the invention of new technology (the word processor) has been layered over the implementation of a very old technology (text) and how this changes the project of writing. This is a book about storytelling and how it is mutated by the technology we use to produce our stories. One of the mental shifts that has occurred within my lifetime has been the shift from linear story production – either via pen or typewriter – and nonlinear story production. I have always written in a nonlinear fashion and it impacts how I personally approach writing. The creative SPACES that we work in shape how we learn and innovate. They change the complexity of the stories and ideas we are able to distill and understand. Kirschenbaum’s book comprehensively examines how the Digital Age has shifted the art and practice of the SPACE we write in. Why This Book Matters to My Work: I have always written as an editor. My priority is always getting ideas recorded digitally. Then, I spent most of my effort writing massaging and polishing those ideas. Kirschenbaum’s book is an exploration of how other authors have reacted to this same technological shift and how it has changed their production of narrative. I apply the realities it describes constantly as I workshop ideas with clients and teach my students. I’ve used them in the creation of this page. (Just did it again…) |

||

Key Quotes“This is the universal reality of writing: the wrenching of thoughts and ideas through the sieve of language, one line, one sentence, on page at a time. But close up against the chasm between composition and inspiration we find – always – material things and technologies.” “Word processing hovers uneasily between the comfortably familiar and the encroachingly alien. Rather than a reimplementation or remediation of typewriting, I prefer to think of it as an ongoing negotiation of what the act of writing means.” |

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):

|

|||

– 18 –

|

|||

Narrative Design |

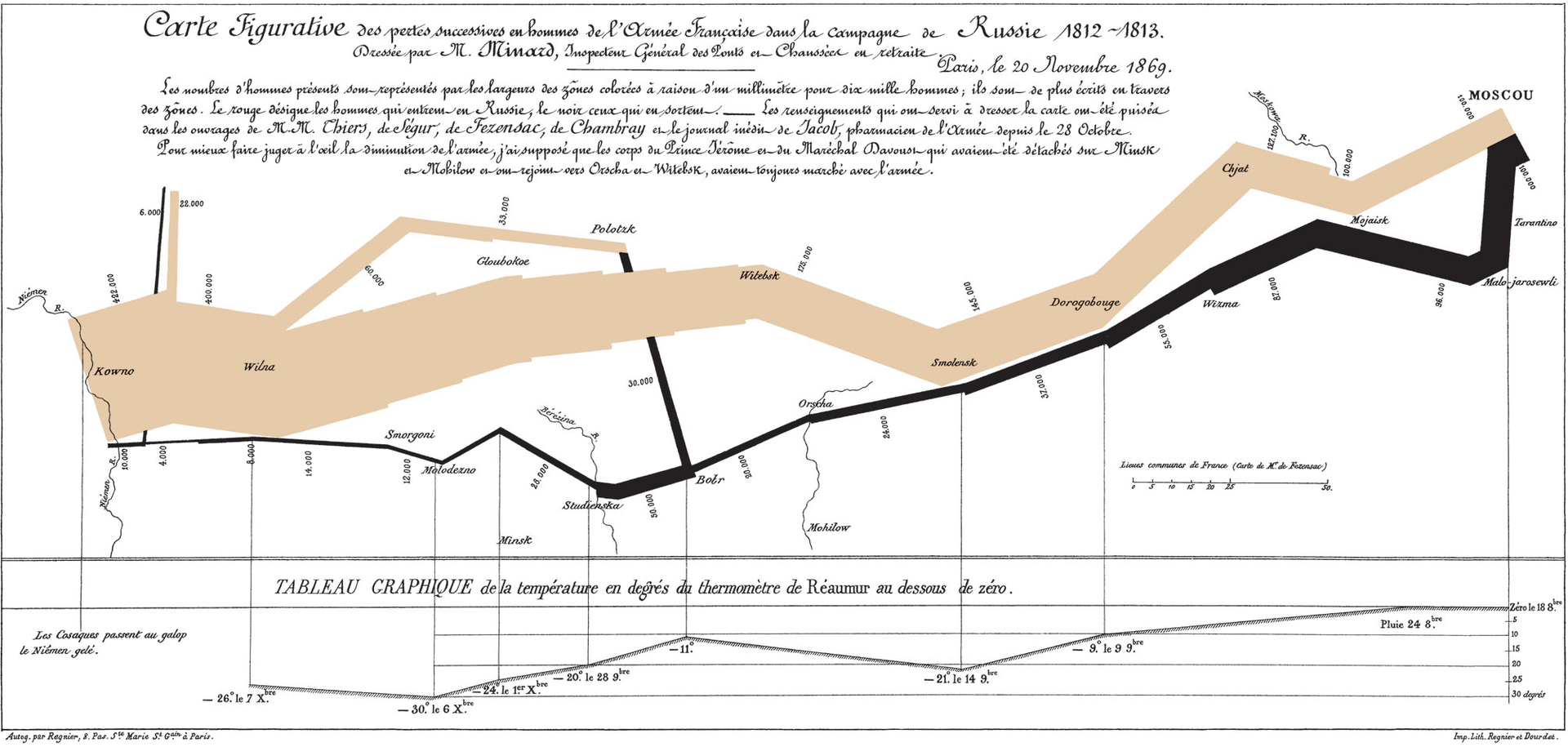

Tufte changed how I communicate information. His books show how to translate complex information into clear visualizations (and how not to do it). As someone who is naturally inclined toward visual thinking through my photography, the transition to more graphic forms of communication came more easily for me, but it’s still a constant effort to make sure I’m paying attention to his precepts as I construct everything from websites to presentations to papers.

The combination of Digital Age tools such as Keynote, Miro, Photoshop, Mindnode and many others with Tufte’s clear exploration of how we can and should present data to a wide variety of audiences make his books indispensable for any digital communicator. Technologists should recognize that they are often communicating such information to others but are also responsible for providing tools (and instruction) for others in how to do the same. Visual communication is a central aspect to how the Digital Age has reshaped narrative. As Discovering Digital Humanity discusses in Chapter 2.1, we now have nearly infinite power over narrative canvases. However, with great power comes great responsibility. As the scope of our SPACES shifts, we need to understand how new media impact our narratives and how much our thinking is rooted in linear, textual thinking about information. Tufte is an important first step to becoming a digital communicator. Why This Book Matters to My Work: I am constantly using Tufte as a lens to show others how to use visual tools effectively to tell the stories that they are trying to tell. The most obvious area where this comes into play is when people create slide decks. As a technologist (and visual storyteller), I’m always trying to suggest to students of all kinds how to tell their stories. |

||

Key Quotes“Principles of design should attend to the fundamental intellectual tasks in the analysis of evidence; thus we have the Second Principle for the analysis and presentation of data: Show causality, mechanism, explanation, systemic structure.” “Imagine that you are a high-level NASA decision-maker receiving a pitch about threats to the spacecraft. You must learn 2 things: Exactly what is the presenter’s story? And, can you believe the presenter’s story? A close reading of a presentation will help gauge the quality of intellect, the knowledge, and credibility of presenters. To be effective, close readings must be based on universal standards of evidence quality, which are not necessarily those standards that operate locally.” |

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):

|

|||

– 19 –

|

|||

Narrative Design |

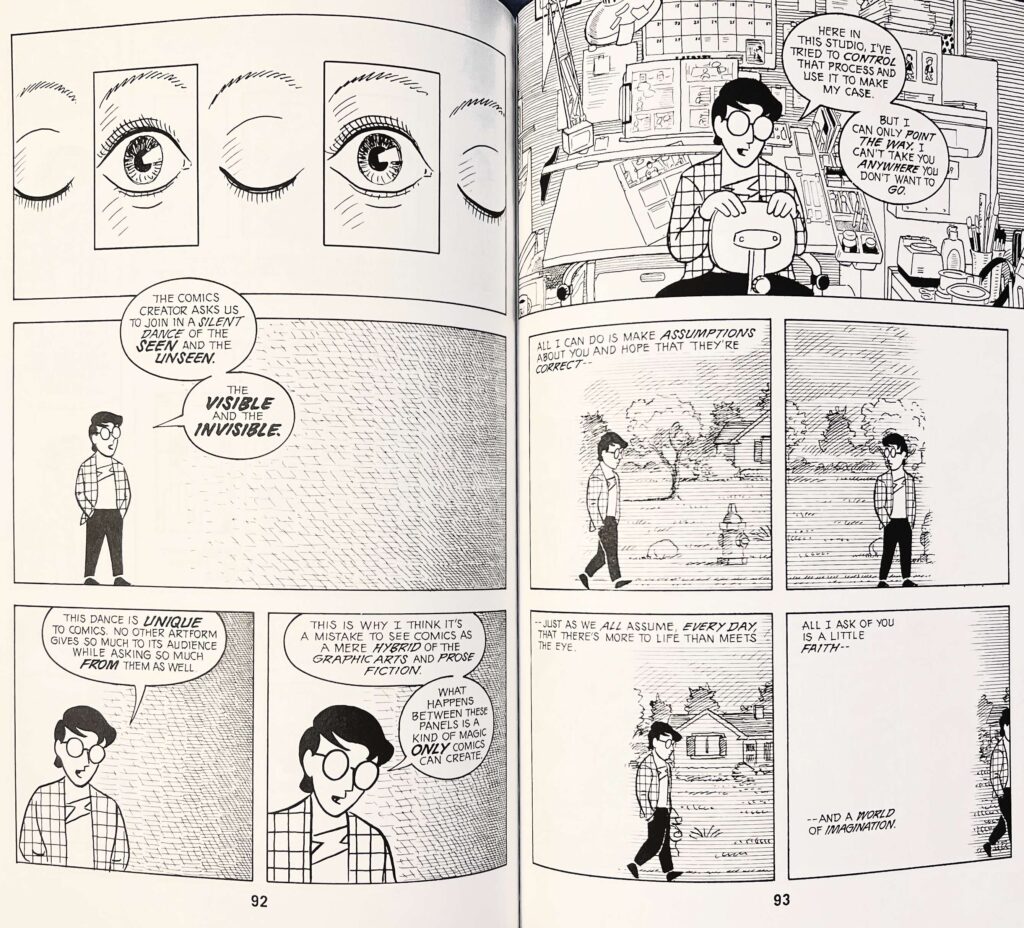

Scott McCloud has been called the Aristotle of comics. He surfaces aspects of visual communication we all take for granted and talks about how we play with SPACE, TIME, and STRUCTURE and how we can manipulate them visually. He uses comics as both his medium and his message to illustrate these points vividly. He is a master of instruction in abstraction.

I love books that make you look at the “obvious” differently. McCloud definitely does that. In that way he helps shift paradigms of thought in unexpected ways. This book was written right as the Digital Age was becoming a mass effect. It deals with a topic that stretches back to ancient times. However, what McCloud shows us here are evergreen concepts of human expression and understanding. Why This Book Matters to My Work: McCloud sets a high bar for me when it comes to visual communication. As a technologist, it is essential that we have a level of mastery over visual communication. Tufte will tell you what (or what not) to do. McCloud tells you why to do it. This is one of those books that always comes popping back at me as I think about how to construct digital stories. We all abstract all of the time and it can be a powerful shorthand for digital communication and storytelling. I make heavy use of the iconography in the Noun Project to help me tell stories. McCloud shows me how. |

||

Key Quotes[Abstraction of Reality] (pp. 92-93)

|

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):

|

|||

– 20 –

|

|||

Narrative Design |

Bryan Alexander’s unique contribution to this section is his broad vision of narrative and how it ties everything from traditional, linear storytelling to gaming into one complex package. Richly illustrated with examples from a range of media, he discusses how digital opens new doors to how we tell and consume stories. For any exploration of digital narrative this book is an essential starting point.

All technologists have to be futurists. We build systems that project technology into the future and, in doing so, push the envelope on the future itself. Alexander brings a futurist’s eye to the construction of stories. In so doing, he shows us how to use digital stories to create visions of the future and how to facilitate those visions in others. Particularly relevant is his extensive exploration of gaming as storytelling. I frequently use games and simulations to help others explore topics in a safe way so that when they strike out for real they feel more confident having gamed out various scenarios. Why This Book Matters to My Work: I refer back to Alexander often as I consider how to design those games. Alexander’s exploration of immersion in stories is particularly relevant to anyone trying engage audiences. I use it in all aspects of my teaching, both to college students and faculty. |

||

Key Quotes“We can start before the Internet, if we choose. To the extent one considers games to contain stories, we could begin with a game called Spacewar, an early storytelling engine that dates back to the 1960s. If we think of world-building as storytelling, the first virtual worlds in the early internet age – all text based! – appeared in the late 1970s, with the first MUDs (Multi-User Dimensions or Multi-User Dungeons).” “Immersion must persist over time, iteratively. A mastered and unchanging game becomes a mere exercise, and an explored space bears little further exploration. Characters that do not change are often derided as fast and undeveloped; the desire for character development assumes an iterative arc. Therefore, successful immersion must progress over time, repeatedly establishing Murray’s sense of enchantment and engagement.” “The player, in other words, can afford to fail, then try again, mixing up a different approach while being able to count on the game world’s consistency. The balance of these two tracks, crafted and emergent, changes from game to game, but the concept remains broadly applicable.” |

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):

|

|||

Part VI: Applied Technology – Human Design

The final section of applied technology could easily be the first. We design technology to support humans and these books talk about different ways that we can build systems of technology around our humanity.

– 21 –

|

|||

System Design |

A persistent theme in this section’s books it that it is the adaptation of humans to technological systems that is the critical factor. One of the novelties of digital technologies is that they are relatively easy to adapt iteratively. This was not the case in the early 1940s.

Lundstrom describes an incredibly complex system stretching from frontline pilots to their squadron and group organizations to the deployment of their carriers and airbases to the logistical and training tail that stretched all the way from the South Pacific to Washington, DC. None of these levels in lived in a vacuum. This book shows how a complex technological system evolved in short time by incorporating its human capital intimately into the process. The US Navy in the opening days of World War II was a system under massive stress. Everyone was improvising how to fight an entirely new kind of war. It is common to think of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor as being revolutionary. However, it was an attack against a fixed and unprepared target. Managing the complex dance of locating enemy ships in a vast ocean, assembling strike groups to attack it with technologies that were not explicitly designed to work together, and, most importantly creating systems of command and control that allowed success is something that the US Navy perfected in the year after Pearl Harbor. It was an iterative process of learning from mistakes. We like to think that the job of the technologist is done once a technology is implemented. This is a fallacy. Technologies are useless if humans don’t use them effectively. This book shows how iterative learning and adaptation at all levels of a system can provide a decisive advantage to the side that practices it. It shows how an understanding of the technology environment is crucial to success of any technology project (and creating functioning carrier strike groups was definitely a technology project of the first order in 1942). Why This Book Matters to My Work: From my beginnings as a technology leader, I have always been fascinated (and frustrated) with technology adoption. I am constantly applying lessons of technology learning and human adaptation that I learned from this book to my technology projects. |

||

Key Quotes“Facing its first acid test was the Navy’s fighter escort theory, and it was none too sophisticated because each fighting squadron and air group generally used its own procedures. Only through hard-earned combat experience bought at the price of many lives throughout 1942 did the experts hammer out a definite escort policy for use by all the squadrons.” “After the outbreak of the Pacific War, he carrier fighter squadrons could not absorb high numbers of green pilots and still remain combat ready. They needed time and tranquil conditions to qualify the rookies, but the strategic situation, such as that with the 5th Carrier Division after the Coral Sea Battle (May 1942), did not permit it. The Zuikaku could not participate in the Midway Campaign solely because her air group could not quickly prepare the green replacement pilots assigned to it…. Lacking advance carrier training groups and reserve carrier air groups (such as the US Navy was forming), they could not make their rookies combat ready. Greater American flexibility in training pilots and shifting squadrons and groups from carrier to carrier paid its way in the Pacific War.” |

|||

Related Titles (honorable mentions):

|

|||

– 22 –

|

|||

Educational Design |

Laurillard’s book is about technology but it almost never talks about technology directly. This is because her focus is on defining the tasks that any teacher or trainer must perform before beginning the selection of the tools for the task. Laurillard spent decades working the UK’s Open University, which was tasked with decentralizing higher education and making it available to wider slice of the British populace. Many hard lessons were learned along the way about the limits of technology.

This book chronicles an ordered design process that works forwards from teaching and learning and provides a framework for adaptive change as we learn more and more about how people actually learn. The vast majority of formalized education is entrenched in an industrial paradigm which Laurillard and others have long recognized as being ineffective. Teaching as a Design Science is designed to provide a pathway forward in response to the rapid evolution of technology. As Laurillard says on page 40: “if we focus on the individual learner trying to grapple with the complex ideas put together by the experts, we have to recognize that for many students the knowledge does not transmit very successfully.” Why This Book Matters to My Work: As a teacher of teachers and students, I have long sought a method for helping both groups navigate learning first and only then engage with technology. Laurillard provides me with the most complete strategy for addressing the challenges of teaching and using technology to augment it that I have found so far. Her thinking has influenced everything from my traditional course design to workshops I build to engage various educational communities. Her six learning actions form the core to the ongoing Teaching Toolset Project I have been facilitating for the ShapingEDU Project at Arizona State University. |

||

Key Quotes“Tools and technologies, in their broadest sense, are important drivers of education, though their development is rarely driven by education.” “We cannot challenge the technology to serve the needs of education until we know what we want from it. We have to articulate what it means to teach well, what the principles of designing good teaching are, and how these will enable learners to learn. Until then, we risk continuing to be technology-led.” “The student is continually interacting with their context of study, and the way the learning environment is organized around them. Their habits and ideas about what it takes to learn develop within this context, which clearly helps to influence the direction of that development.” |

|||

– 23 –

|

|||

Educational Design |

Lave and Wenger emphasize the importance of community in all aspects of learning. I would extend this idea to innovation as well. We learn from others and from ourselves informally far more effectively than we learn alone.

Technology of all kinds should be directed toward creating communities of humans learning from one another. Whether you are creating actual learning spaces or innovation spaces, the principle is the same. As many other titles on this list (Laurillard, Johnson, McNeely and Wolverton, etc.) point out, it is in our human networks that we thrive, grow, and learn. They are also where we are most human. Why This Book Matters to My Work: Whether I am creating formal learning spaces, informal learning spaces, or networked improvement communities, the concept of communities of practice is never far from my mind. I want to use technology, whether we are talking about a room and furniture or an online space, to bring people together. Communities of practice are fragile and must be nurtured at every step along the way. They are the Holy Grail of educational practice but they also matter a lot to organizations of all kinds trying to harness the creative potential of employees. Creating meaningful communities is a central focus in all of my technology designs. |

||

Key Quotes“[T]his conception of learning clearly was more encompassing in intent than conventional notions of ‘learning in situ’ or ‘learning by doing’ for which it was used as a rough equivalent. But, to articulate this intuition usefully, we needed a better characterization of ‘situatedness’ as a theoretical perspective.” “The person has been correspondingly transformed into a practitioner, a newcomer becoming an old-timer, whose changing knowledge, skill, and discourse are part of a developing identity – in short, a member of a community of practice.” |

|||

|

||||||||||||

Part VII: Designing New Realities

The final section of this list of books really only contains one title. That is because we can only design new realities if we are willing to take a hard look at the realities we have. We can apply technology in support of existing realities or use technology to construct new ones.

– 25 –

|

|||

Constructivism |

This is where is all starts for my thinking on technology. Foucault casts a critical eye over every aspect of “modern” society. He is a key thinker of postmodernism. Every technologist needs to understand how we construct physical, organizational, and mental structures of power to manage modern societies.

I first read Foucault in graduate school but it was only when I started designing technology that I am became aware of the true power of what he was saying. Foucault examines how technology is used not only to control the natural world but also to control our fellow humans. Pay particular attention to his discussion of Jeremy Bentham’s “Panopticon.” Originally designed as a prison along rationalist lines, in Foucault’s writing it comes to represent the powerful (the guards) having a view of every aspect of the society’s lives. This idea is everywhere in our world today. I see it in the architectural panopticon of my children’s high school to an array of digital panopticons designed to monitor and monetize the activities of their users. It is a natural instinct for humans to build to control the world around them. After all, isn’t that what technology is for? However, we always have to be sensitive to likelihood that the powerful will seek to control societys. If we want to design for equity, we first have to understand how many of our systems and technologies are designed for inequity. Why This Book Matters to My Work: I am constantly thinking as a constructivist as I approach my writing, space design, and technology design projects. This means that I am always looking for panopticons and for how we use language to stifle other voices. This includes technology itself. I avoid language that is exclusive and designed to make me look “smart” when helping people understand technology. Technology is about empowering humans, not selling gobbledygook. Foucault is a constant reminder of the power I have over others. My job is to break down walls, not impose order and control. |

||

Key Quotes“On the contrary, it exists; it has a reality; it is produced permanently around, on, within the body by the func tioning of a power that is exercised on those punished-and, in a more general way, on those one supervises, trains, and cor rects; over madmen, children at home and at school, the colonized; over those who are stuck at a machine and supervised for the rest of their lives. “ “The theme of the panopticon-at once surveillance and observation, security and knowledge, individu aiization and totalization, isolation and transparency-found in the prison its privUeged locus of realization. Although the pan optic procedures, as concrete forms of the exercise of power, have become extremely widespread; at least in their less con centrated forms, it was really only in the penitentiary institutions that Bentham’s utopia could be fully expressed in a material form.” |

|||