Life is complicated. At any given moment, a thousand things are happening which impact my life. An exponential number more will impact my life in the future. Most of these things are things you only have a vague awareness of, at best. Additionally, I manage systems in my body, from the infinite complexity of my mind, to the autonomic beating of my heart, to complex interactions between the three as my fingers dance across the keyboard to type these words.

As we teach, we are also constantly abstracting. I explain the complex workings of the US government using models and simulations. A biology professor does the same as she explains the complex interactions of cells in a biological system. Neither one of us would claim that we are doing anything more than abstracting reality to make it understandable to our students. One of my favorite jokes is the one about the student who studies Intermediate French to prepare for a trip to France. When she gets there, she discovers they don’t speak intermediate French in France. The joke is that “Intermediate French” can only ever hope to be an abstraction of the richness of the living language as they practice it in France.

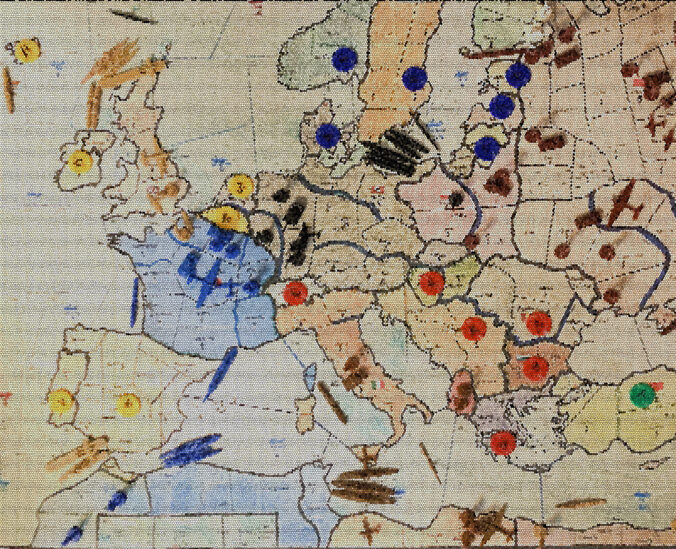

Games also abstract reality. Games have always fascinated and frustrated me, because they try to abstract complex actions into repeatable activities. It’s always a balancing act between accuracy and gameplay. Some games are very abstract, such as Go or Chess. Much like mathematics, they lean into gameplay and abstract mental interactions. At the other end of the spectrum, war games often attempt to model complex historical and technical interactions while acknowledging the role of chance in historical outcomes.

In his excellent book, Of Dice and Men David Ewalt argues that one attraction of more open-ended roleplaying games such as Dungeons and Dragons is that most of the activity involves storytelling rather than arguments about bounding the universe. While there are core rules, the logic of the experience is constantly evolving in the minds of the participants. Ewalt says that the frustration of war gaming is that, “only 10 percent of the match is really spent playing. Half the remaining time is spent arguing about history and the other half arguing about the game’s rules.” (Ewalt, p. 52) I find this to be a rather accurate breakdown of the experience.

However, I think that attempts to align history with rule making are of immense value. I have been playing wargames with a group of friends (all of who work at the college with me) since the early 2000s. For most of that period, we engaged in an ongoing iteration of the classic Axis & Allies wargame. Now, if you knew the printed rules of the game, you’d hardly recognize the version we were playing.

One of those friends once reflected to me that he wondered whether we were engaged in an immense time-wasting activity. I pointed out that as administrators and teachers, the construction of systems of rules, whether we’re talking about course structures reflected in a syllabus or the design of spaces and programs in which those courses lived, was the same mental exercise we engaged in as we attempted to construct systems of rules for the game. The learning was in the invention.

We engage in a constant modeling of reality as part of our daily exercises in sense making. Rules connect our perceptions of one another. What are the rules for sharing my ideas? What rules can I construct that will connect my realities with those of my students? The projects in ShapingEDU are also trying to construct their own models of effective engagement with the world. Some do so directly, such as with Ruben Puentedura’s Black Swan and Serious Play initiatives. Others seek to model a sense of the world, such as the Pandemic Teaching Reflection project. My Teaching Toolset Project is seeking to codify a set of rules that will model interactions between actual teaching behavior and the tools we use to carry it out. The Broadband and Student Voice projects are trying to construct maps through systems of governance and education to achieve their goals.

We are dealing with seriously complex systems in these projects. Explicitly or implicitly, we are trying to create or understand sets of rules that abstract reality. This brings me back to my original conundrum: How do you model complexity while maintaining gameplay? There’s a reason that most people don’t like to play complex games such as wargames. New players must confront a steep learning curve before they even get to the part where they’re engaging in strategy. The level of detail can be overwhelming.

Technology doesn’t help us here. Modeling reality in most video games results in mental (or physical) overload as you try to mimic body movements through a keyboard that you would otherwise engage in reflexively. Extending that to a team, as many sports games do, only multiplies that effort. In contrast, competition in Dungeons & Dragons takes place almost entirely in the imagination (with a little help from the dice).

Some may argue that I’m conflating modeling with gaming, the latter being subject to the whims of chance. I would counter that by saying modeling works in a Newtonian World but that a relativistic world operating under the principles of emergent design we cannot escape probability and uncertainty. Uncertainty inevitably introduces elements of chance and randomness. Frameworks such as simulations and games help us make sense of random outcomes and to adjust the rules going forward.

We need to pay attention to the “rules” we are following and recognize that they are themselves part of the game and subject to modification. Explicitly designing sets of rules helps us better understand the compromises we are forced to make in the service of insight. We can create new and novel ways of playing games of understanding, such as the clever modeling of university leadership through matrix gaming that Bryan Alexander ran with his graduate students at Georgetown University. I am always looking for new and better ways to simulate and game systems and to systematize games. We have a tremendous opportunity to do the same with ShapingEDU.

We have too many closed games in our world that are the equivalent of Intermediate French. Understanding the mechanics of how we construct games can help us construct richer systems of understanding. To do this, we first must recognize these limitations and never stop questioning and refining the rules. Wherever possible, we should create open-ended games, such as Bryan’s matrix approach. However, sometimes the act of creating the rules/constraints provides new insights into the challenges we face. Creativity requires constraints. However, rules should be explicit and subject to iteration. We should never forget that our ability to model a complex world depends on the lenses we use to see it. The rules of the games we construct form the design parameters of those lenses. Let’s make sure we use them to see the world in new ways.