Time is our only truly non-fungible asset. Deficits of money can be made up but deficits of time are impossible to recover. As teachers, we struggle with this every class. We understand that time spent with students is absolutely precious. It can never be made up once the clock at the end of a term runs out. It is difficult recoup even within the context of a single class session. Time is a truly scarce resource.

Scarcity doesn’t always breed perceived value, however. Students often struggle to find motivation. They sit through classes out of a sense of obligation or a belief that showing their faces will increase their grade. Their perception of time in an instructional session can often stretch toward the infinite (“When is this going to be over?”).

The reality is that we waste a lot of time in any class. The density of knowledge that we can ask our students to absorb within a given live session is even more constrained than that marked out by the clock hands. Lessons in a single class session can usually be counted on one hand, if that. One of my grad school professors (the only one who bothered to teach me anything about teaching) told me that you can’t expect students to absorb more than 3 points in a given lecture. Your challenge as a teacher is making sure that they absorb the right three points. I have found this to be a good yardstick of what I can realistically accomplish within a single session but even that is often an optimistic measure.

The pandemic and remote teaching showed many of us the limits of synchronous teaching. Students weren’t even engaging to the same level as they had during in-person sessions (and that was a low bar). The fact is that much of a given hour of synchronous instruction is repetitious. If it’s repetitious it doesn’t need to be synchronous. The first 5-10 minutes of my classes are usually spent checking roll, making announcements, and recapping highlights from the last session.

None of those things need to take up precious synchronous time and can be shifted into asynchronous tools. Taking roll can be automated by having students put their names in a saved chat or with numerous other tools. It is better to send announcements through an online course shell. Recapping lectures is unnecessary if you record a Zoom session and post it for later review.

Expository talking, aka lecturing, also took a hit during remote teaching. Many of us practice some form of the Socratic method. We quickly discovered that question-and-response really doesn’t work well with a bunch of anonymous black boxes in a Zoom session. Like announcements and recaps, moreover, the same level of interaction can be achieved through pre-recording lecture highlights and pushing that off into asynchronous time.

Using various methods, therefore, I liberated close to 80% of my synchronous time from the time vault during remote instruction. This drove me to think hard about what to do with the remaining time. Attention spans online are even shorter than they are in person. There was also an expectation that, since the session was being recorded, the student could go back and review the tape if there was something he or she missed.

The key to making synchronous time as productive as possible was doing something instead of just talking about it. I had always nibbled around the edges of this in my in-person classes but I never really trusted student-driven work to actually drive the class. I wanted to control the narrative in the classroom to make sure we “covered the material.” Giving control of the pace of the class to the students was a scary prospect and, after all, wasn’t I, as the “expert in the room,” abdicating my responsibility?

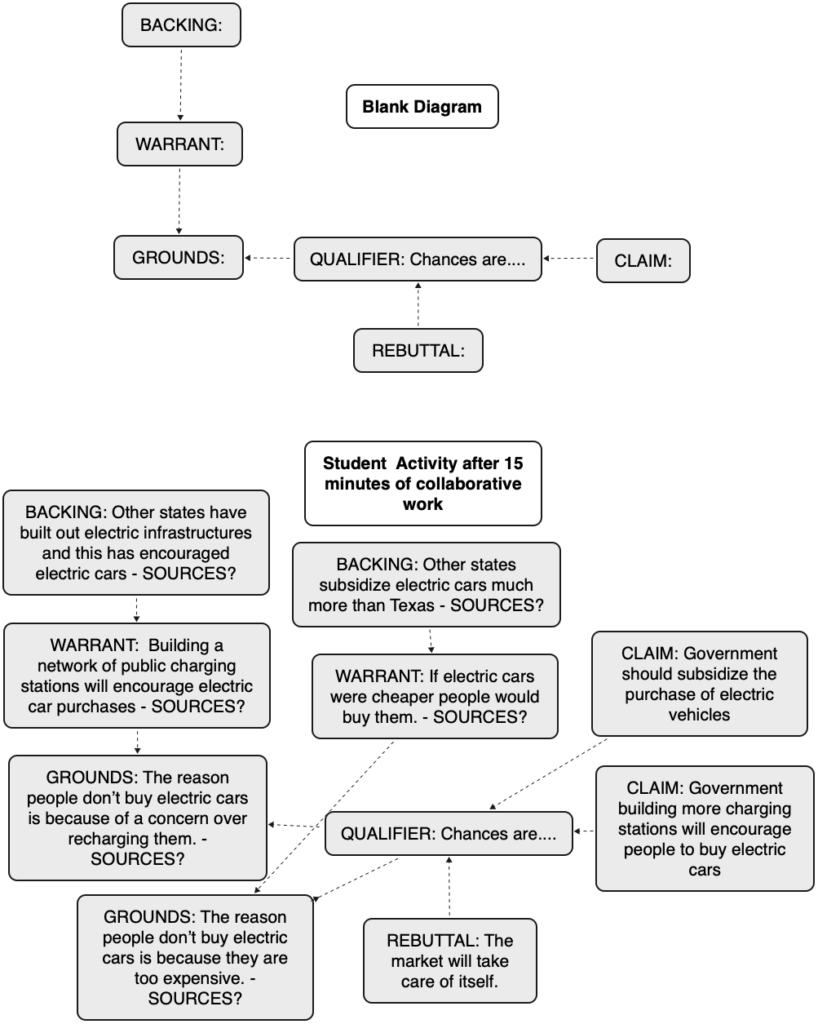

Faced with obvious indifference using online tools, it was clear that I needed to pivot decisively toward creating moments centered on the students, not the material. I would have to trust that the material would take care of itself. In in-person settings simulations often were a good way of creating immediacy and active learning. However, this was challenging in an online setting where interpersonal interactions are often more stilted. Instead, I asked myself where my students needed the most help. I started working back from my assessments and determined that analysis and argument were conspicuously absent from most of their work. The solution (HT Ruben Puentedura) was to introduce the Toulmin Argumentative Method directly into my live sessions.

This work consumed many class sessions as we dissected each students’ argument. My knowledge of the subject plus techniques of argumentation and research were brought to bear as I walked them through the steps of constructing an argument. The students were then tasked with finding sources that supported their arguments. In this way I sought to develop a community centered around intellectual inquiry. The tools used were very simple. I used Zoom and shared my screen with a concept-mapping tool. After the sessions I cleaned up the diagrams a bit and shared them on Canvas. This would have been more difficult to do using traditional, in-class tools. But it drew power from the collaborative synchronicity of the work online.

The central goal of this activity was to stimulate conversations and group practice to collectively unlock the riddle of their research projects. As Diana Laurillard points out, conversations are central to any learning experience. We can have most kinds of conversations asynchronously but they are reshaped, some might say limited, by their lack of immediacy. The key to generating effective conversations is creating opportunities for the unexpected and these are far easier to achieve synchronously. This is a more important distinction than whether that interaction happens in close proximity or at a distance.

We should not assume that returning to “traditional” classrooms will automatically return us to where we want to be, forgetting the lessons learned from remote instruction. As we discussed in a previous blog, most “traditional” classrooms did not take full advantage of the potential for the student-teacher relationship. Conversation was often one way. Over the last decades, learning space design has worked hard to overcome these initial biases. However, even the most innovative classroom will lose much of the benefit of immediacy if the teacher uses it to teach in a “traditional” way.

Digital Age tools can speed the flow of ideas but they have to be applied strategically in order to achieve the “decisive moment” where deep learning occurs. Information alone is not sufficient to stimulate ideas. Those ideas must resonate within the community of learning. Ideas are central to our humanity. Therefore, if we want to share our humanity, we must also share our ideas. If we want to teach in a learner-centric world, we must find ways to connect our humanity. This is where digital tools can help us. They give us tremendous power to amplify how we connect humans to each other. This reality forms the core of all synchronous learning experiences.

Good teachers shape realities and do so with intentionality. Synchronous experiences are the most visceral realities that students can experience in their learning process. These are the spaces where we can “perform” as teachers. However, they only work if they are also spaces where our students can perform as well. Teaching is all about achieving that “a-ha” moment in our students.