These articles were originally published on PBK.com in 2017.

What are Creation Spaces?

Creation spaces are spaces that facilitate creativity among their users. As technology creates opportunities for building and making new things that were previously the domain of industrial concerns, these spaces give students the ability to create tangible objects as part of their learning journeys. The traditional version of this kind of space is the art studio, which maintains its relevance and is enhanced through the addition of new technologies. However, new kinds of spaces are emerging to support specific kinds of creation. On the software side, One-Button Studios allow students to create videos and other multimedia content easily. On the hardware side, a wide range of MakerSpace environments allow students to create everything from robots to sculpture to furniture in a single environment.

How big an Investment are Creation Spaces?

Investments in creativity spaces can range broadly from a few hundred dollars to millions of dollars for a fully outfitted MakerSpace. Space considerations range from a few dozen square feet for an in-class Creation Station to 15,000-20,000 square feet for a Fabrication Lab that has a large functional range extending to woodshop and metalshop services. Staffing costs also range from practically nothing in a One-Button Studio to a specialized instructor required to maintain safety in a woodshop-type environment. Middle-of-the road environments like the Design Lab allow institutions to right-size facilities to maximize resources to their students while minimizing costs and overhead.

What are the benefits to instruction?

The economic logic driving down costs in technology and staffing are also driving change in the private sector and making skills acquired in this kind of environment very desirable on the job market. Companies are recognizing the benefits of having in-house design and fabrication over the delays and costs traditionally associated with prototyping. In addition, we are seeing a wide range of entrepreneurial activities rising in response to the low startup costs associated with many of these technologies. Learning by doing and the development of a portfolio is a very desirable educational outcome facilitated by these kinds of spaces.

Contents

Creation Station

What is it?

A Creation Station is a micro-MakerSpace designed to fit within the confines of a classroom space. The idea is to allow for spontaneous creativity and support of programmatic activities within the classroom. The equipment is tailored to be accessible and unobtrusive when not in use, but to give teachers and students easy access to Maker tools.

What are the benefits to instruction?

Introducing a Creation Station available in a classroom environment gives a teacher the ability to introduce directed, experiential activities on the fly. This has significant impacts on learning outcomes. Professor Michael Prince, in a review of the Active Learning literature, writes, “Introducing activity into lectures can significantly improve recall of information while extensive evidence supports the benefits of student engagement.” (Prince, Michael, “Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research, Journal of Engineering Education, July 2004)

Sample Equipment List (approximate cost $1500-3000 per room):

- 3D Printers (Quantity 2)

- Silhouette Curio Vinyl Cutting Tool (Quantity 1)

- Arduino Starter Kit (Quantity 1)

- Raspberry Pi Starter Kits (Quantity 3)

- PCs or laptops (Quantity 1-3)

- 650 Piece Lego Basic Bricks (or equivalent) (Quantity 1)

- Little Bits Electronic Base Kit (Quantity 1-3)

- Misc. Supplies (Filament, Vinyl, etc.)

Design Lab

What is it?

A Design Lab is a lightweight MakerSpace designed to fit into a classroom-sized space. Through a careful selection of tools it can perform many of the functions of a full-sized Fabrication Lab without the specialized infrastructure and safety concerns of a more robust setup. Another critical feature is that the space should be as accessible (and visible) to the campus as possible. Students will be curious about the activities taking place there and will want to participate, but only if they know that it exists.

How big an Investment is a Design Lab?

The idea behind the D-Lab is to assemble a usable set of light tools into a resource space. Typically, 700-1000 square feet is sufficient to achieve this task. It is important to leave a portion of the space available for people to spread out their projects. Heavy-duty (hard surface or butcher block) tables are recommended for this area. A selection of 3D printers is usually expected. Other equipment can include vinyl cutters, PCs, soldering irons, miscellaneous electronic components, and a standard set of hardware tools. If minimal ventilation is possible then a laser cutter is a good tool to have in this space as well. All told the equipment in this space should total no more than $20,000-30,000. Adequate power is critical. If this is a conversion project, a computer lab is a good choice for a basic space as those spaces typically have sufficient power for the various devices in the space. If not, then electrical upgrades through the addition of outlets might be required.

Ongoing expenses are fairly manageable. While it is important to have a full-time staff member overseeing the space, part-time student workers and even volunteers can be used to staff out the space. Minimal skills are necessary to run equipment in this kind of space, and many of them will likely have to be learned on the job in any case.

As far as supplies are concerned, a small supply budget is appropriate for programmatic activities and demonstration projects. However, the expectation for students is that they bring their own supplies into the space. At the college level, college bookstores will often stock 3D filament. Filament is also widely available online from vendors like Amazon. Other supplies will commonly be found in home improvement stores like Home Depot and Lowes.

What are the benefits to instruction?

The Department of Education says, “Through making, educators enable students to immerse themselves in problem-solving and the continuous refinement of their projects while learning essential 21st-century career skills, such as critical thinking, planning, and communication.” The benefits to having a space such as the D-Lab in every school, particularly at the Middle and High School levels are significant. What is even more exciting is that every one of these kinds of spaces that we have created have generated unexpected ideas and benefits to both the users and the schools in which they are located. Students have developed innovative solutions to everything from school signage to food production. They are essential breeding grounds of ideas in the 21st Century.

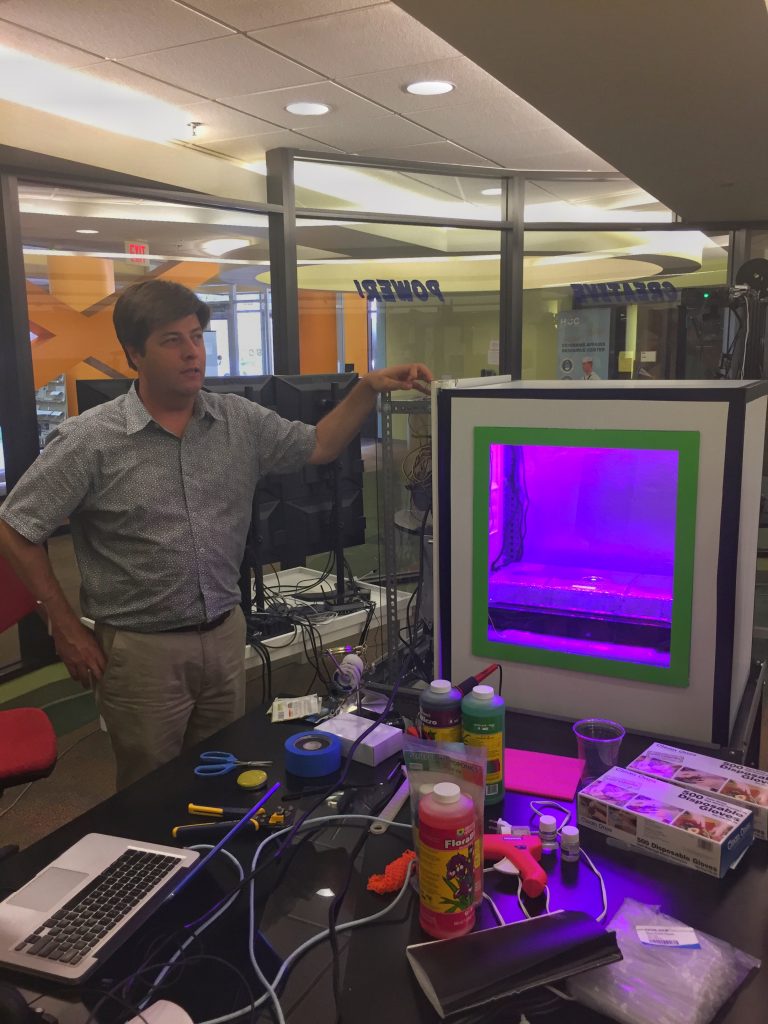

A student-built Food Computer at Houston Community College’s Alief D-Lab

RESOURCES:

- MakerED: http://makered.org/resources/spaces-places/

- We Are Makers: http://wearemakers.org

- MakerSpace Activities Suggestions: https://www.makerspaces.com/makerspace-ideas/

- Project-based Learning: http://www.bie.org/blog/traditional_school_imperils_kids_they_need_to_be_innovators?utm_content=buffer4ae36&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer

- Schools are Missing What Matters About Learning: https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/07/the-underrated-gift-of-curiosity/534573/

SAMPLE EQUIPMENT LIST:

- 3D Printers (6-8 of various types)

- Laser Cutter (optional) – Glowforge could be a game changer in this area because it doesn’t require additional ventilation like more traditional laser cutters

- PCs (6-8)

- USCutter 34” Vinyl Cutter (1)

- Arduino Kits (1)

- Little Bits Kits (2-4 various kits)

- Raspberry Pi’s (10-12) – students often purchase their own

- Toolbox and basic tool set (1)

- Butcher block or other hard surface work tables (3-5)

- Misc. Supplies (filament, vinyl, etc.)

Fabrication Lab

What is it?

The Fabrication Lab is more typical of what most people think of when they hear the term “MakerSpace.” In addition to the tools typically found the Design Lab these kinds of spaces will also typically include advanced fabrication areas such as Metal Shops, Wood Shops, and Machine Shops that require safety protocols and specialized staffing.

How big an Investment is a Fabrication Lab?

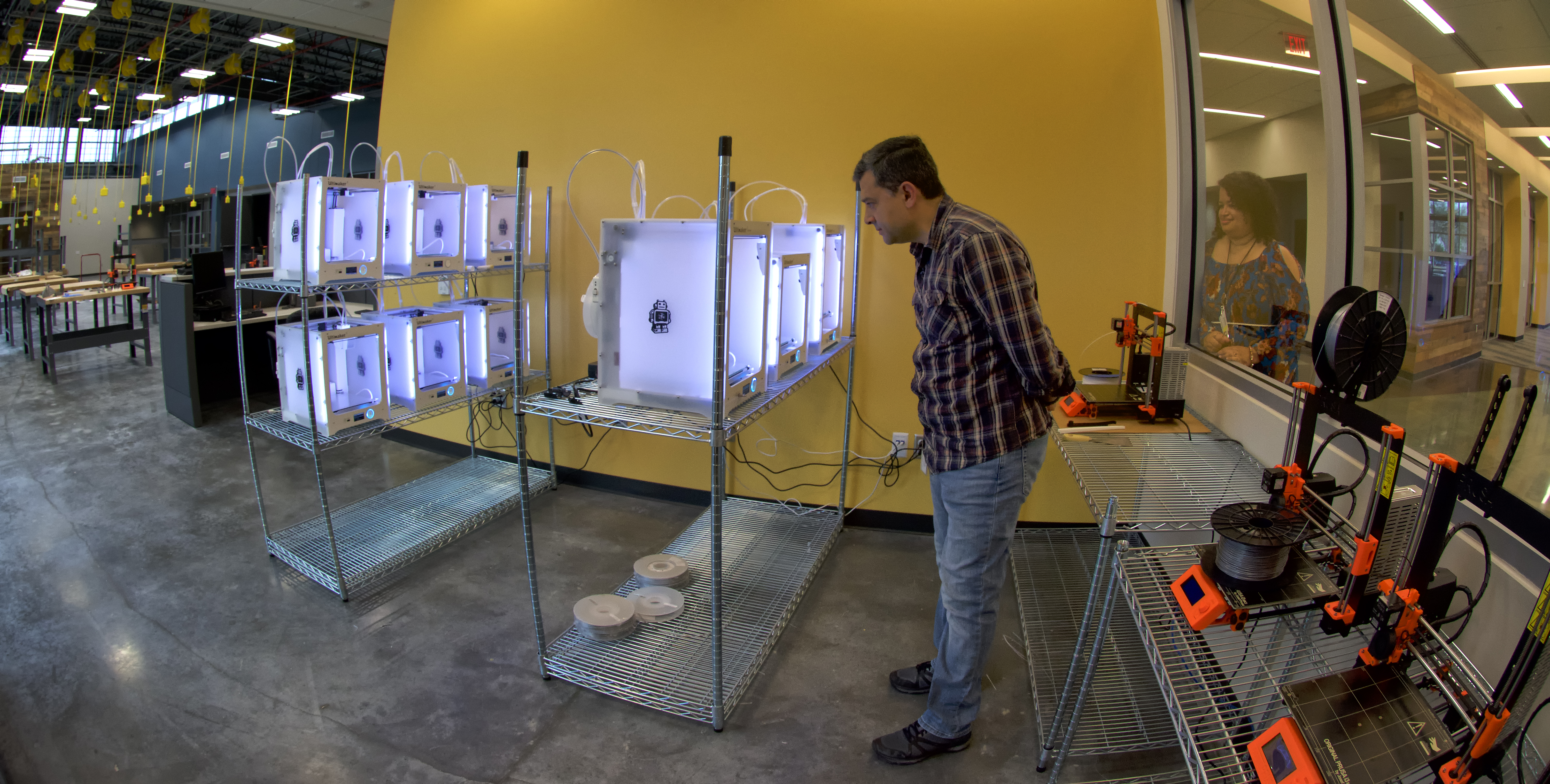

The investment in a Fabrication Lab is not trivial and schools need to go into the development of this space with an understanding of the staffing needs required to successfully operate such a space. Like other MakerSpaces, the Fabrication is most useful when it is treated as a resource like a library and is accessible to the community (either inside or outside the school) as much as possible. It should be treated as a collection of tools designed to facilitate creative activity. The TechShop design is a creative approach that allows for the segregation of low-risk equipment, generally following the model of the Design Lab from the more dangerous wood shop, metal shop, or machine shop components. The MakerSpace at the West Houston Institute was designed using this model.

The West Houston Institute MakerSpace. Areas in Green are generally accessible and contain equipment that can be facilitated by part-time employees. Access is limited to the areas in red because they contain equipment that could be hazardous and need to overseen by specialists in the operation of that equipment. We would anticipate over time that equipment will increasingly be deployed into “green” areas and provision should be made to convert one or more of the “red” areas into a more accessible zone.

The Fabrication Lab has the greatest flexibility when it comes to the final components in the design and can be highly customized for programmatic purposes. For instance, a metal shop or wood shop might not make sense for some structures but perhaps an expanded machine shop or a specialized area focused on automotive technology could be substituted for those areas in the plan.

Issues of access also need to be considered from a safety standpoint. Increasingly, you can do with a very safe laser cutter what was previously the province of much more dangerous tools like bandsaws and jigsaws. Ultimately, the space may need to be reconfigured to allow greater access to areas that have become substantially safer to operate.

The Main Assembly Area of the West Houston Institute before equipment is installed. Note the flexible ceiling power and the open deck that allows for maximum flexibility for future equipment changes. The Wood and Machine Shops are on the far side of this space but still visible through windows. The idea is to allow for scaffolding users from less complex tasks taking place in the Main Assembly Area (3D Printing, Electronics, Laser Cutting, etc.) into the more complex areas.

Wherever possible, accessibility of the tools needs to be considered when drawing up an equipment list. Finally, as tool costs are dropping rapidly and the technology is shifting so fast, equipment should be one of the final items purchased in any building process. This is because the costs of many of these technologies can drop significantly from the time of specification to the time of purchase. For instance, similar 3D printers dropped in price from $3500 to $500 over the course of the development of the West Houston Institute MakerSpace. These kinds of price adjustments, coupled with the emergence of new technologies that could do the same kinds of jobs at a fraction of the cost of the original solution, resulted in an overall savings of between 40 and 50% in the equipment budget of the project totaling almost half a million dollars.

Staffing is also more complex in these kinds of spaces. In the “safe” zones, staffing the area with part-time students is still an option but the more complex areas such as the wood shop, metal shop, and machine shop will require specialized staffing, usually faculty, trained in the safe operation of the equipment there. The more staffing, the more accessible the space will be, and therefore evening or night staffing might prove necessary. Certified volunteers might be an option in some areas, especially if you intend to allow community access to the space during non-instructional hours.

If your model allows it, off-hour use can become a profit center for the space. Arizona State University has developed a partnership with TechShop in Phoenix to operate such a space shared by students and entrepreneurs from the community. It is possible to replicate this model without a private partner and different economic models may be appropriate for different circumstances.

What are the benefits to instruction?

We have already discussed the benefits of Making extensively in the sections on Creation Spaces, Design Labs, and in the blog Hacking School. Creating a broader set of tools will benefit a wider range of programs and curricula than the less complex spaces. At the High School level, CTE programs can and should be rethought with Making in mind as Making creates a more flexible path toward the same learning outcomes. It also future-proofs the spaces far more effectively than more technologically (and architecturally) rigid spaces do. At the college level, more advanced programs in the STEAM fields will be given access to a wider range of potential projects for their students. Additionally, bringing in entrepreneurs, engineers, artisans, and craftspeople from the community brings in a whole range of “teachers” capable of providing valuable lessons and even partnerships for students working in the space.

RESOURCES:

- MIT FabLab: http://fab.cba.mit.edu/about/faq/

- MakerED: http://makered.org/resources/spaces-places/

- We Are Makers: http://wearemakers.org

- MakerSpace Activities Suggestions: https://www.makerspaces.com/makerspace-ideas/

- Project-based Learning: http://www.bie.org/blog/traditional_school_imperils_kids_they_need_to_be_innovators?utm_content=buffer4ae36&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer

- Schools are Missing What Matters About Learning: https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/07/the-underrated-gift-of-curiosity/534573/

EQUIPMENT LIST: There are many configurations for Fabrication Labs and this will have a significant impact on the equipment list. The best way to approach the equipment list is to develop a floor and then customize based on programmatic needs. MIT has developed just such a floor through its Fab Lab Standard. This equipment list can be found at:https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1U-jcBWOJEjBT5A0N84IUubtcHKMEMtndQPLCkZCkVsU/pub?single=true&gid=0&output=html

The One-Button Studio

A One-Button Studio at Houston Community College

What is it?

Penn State University originally created the One Button Studio as a solution to eliminate barriers to multimedia production, especially video, workflow. Its design is meant to provide students and faculty who have little experience in video production with the ability to seamlessly produce high-quality content for assignments, podcasts, online learning, and a host of other uses.

The workflow is designed to be extremely simple. The user enters the room with a USB flash drive and inserts it into a reader. There is literally a button that is pushed which fires up the lights, turns on the camera, and starts a countdown timer. The user positions him or herself in front of the camera and makes a presentation. At the end of the session, the button is hit a second time and the system encodes the video into a compressed file. In a few seconds users have a finished video on their flash drives that can be immediately uploaded to a wide range of online platforms.

The system consists of a ceiling mounted lighting system, a Mac Mini computer, a microphone, and a digital video recorder. All of these are tied together with a simple set of controllers borrowed from home automation systems.

The biggest design/budget question institutions have to ask themselves is what kind of display system they want to give users of the system. The simplest solutions put up a green screen (Rotoscope) or a background for the speaker. A wide throw projector, however, when coupled with a second PC, gives users access to PowerPoint, the Internet, and other technologies to enrich their videos. Adding touch through a system such as an Epson Brightlink interactive projector allows users to seamlessly interact with that content.

How big an Investment is The One-Button Studio?

In its simplest configuration you can set up a One-Button Studio in 80-100 square feet. Some electrical work is usually required to mount the lights to the ceiling and, if necessary, to mount the projection system. Electrical outlets will be needed for the computer(s) that drive the system as well. With those pieces in place the technology is relatively inexpensive. A basic system with a simple backdrop will cost around $7000. Adding a second computer and projection system adds $3000-5000 to that cost.

Since most of the components in this system are off-the-shelf computer components most IT personnel will be able to support this system with minimal training. The operation of the system requires little or no staff. One institution we have worked with simply has a key to the room at the front desk of the library and students are responsible for checking it in and out. The system is self-operating so no dedicated staff is required.

What are the benefits to instruction?

“We live and work in a visually sophisticated world, so we must be sophisticated in using all the forms of communication, not just the written word.” – George Lucas

New state and national educational standards are emphasizing the importance of creating across a broad range of media using technologies that are increasingly available to students. The problem to this point has been one of access, both in terms of cost and the skills required to operate video equipment. Full-blown studios can cost more than a million dollars and require specialized staff to operate them. Most institutions cannot afford this kind of investment at scale. As a result, students are unable to access professional video production. The One Button Studio solves the access problem by providing a relatively inexpensive solution that doesn’t require specialized staff, yet produces professional-looking content.

The uses of this technology in instruction are expansive. At Penn State in the first two academic years after constructing the One Button Studio, over 8,800 students – more than 10% of the main-campus’ student body per year – recorded well over 13,000 videos equating to a staggering 658 hours of recording. At other institutions students have created entrepreneurship pitch videos, mini lectures (teaching is one of the most effective ways of learning), club announcement, and many other kinds of videos. Faculty members have recorded short videos of particularly thorny instructional items such as solutions to complex equations or explaining the technicalities of the Senate committee structure. These examples clearly demonstrate that the One Button Studio represents a tool that can be applied to a wide range of educational challenges and needs.

In the end, therefore, getting students to play with ideas is what matters most, and very few basic textbooks do this effectively. Ironically, this is also where my students have their greatest deficits – probably because most of their education up to this point has revolved around basic textbooks. The teacher becomes the one who is ultimately responsible for teaching the rigor involved in thinking about important ideas and concepts such as who is responsible for the fiscal cliff or the general dysfunctionality of our government. More advanced books do contain important ideas, but the basic textbook rarely goes beyond the descriptive stage. New media offers more compelling ways of presenting such information. Also, students’ curiosity is more easily stimulated when we push them to reach conclusions on their own rather than force-feeding them information via the mechanism of a textbook.

In the end, therefore, getting students to play with ideas is what matters most, and very few basic textbooks do this effectively. Ironically, this is also where my students have their greatest deficits – probably because most of their education up to this point has revolved around basic textbooks. The teacher becomes the one who is ultimately responsible for teaching the rigor involved in thinking about important ideas and concepts such as who is responsible for the fiscal cliff or the general dysfunctionality of our government. More advanced books do contain important ideas, but the basic textbook rarely goes beyond the descriptive stage. New media offers more compelling ways of presenting such information. Also, students’ curiosity is more easily stimulated when we push them to reach conclusions on their own rather than force-feeding them information via the mechanism of a textbook. This semester I am using Wikipedia and my own notes posted online as a starting point. I will then task students to consider questions like “Who is responsible for the fiscal cliff, the president, Congress, or someone else?” These will be collaborative efforts, and the output will be a combination of a presentation open to critical response as well as an online blog entry subject to comment and response.

This semester I am using Wikipedia and my own notes posted online as a starting point. I will then task students to consider questions like “Who is responsible for the fiscal cliff, the president, Congress, or someone else?” These will be collaborative efforts, and the output will be a combination of a presentation open to critical response as well as an online blog entry subject to comment and response.

If it isn’t clear by this point, I am firmly convinced that if higher education is in the business of selling “scarce” content in an age of Google, MOOCs, and Wikipedia, institutions of higher learning will become obsolete. If our students’ ability is confined to memorized mastery of a subject whose currency is out of date the day they graduate, they are equally doomed. I am also not naïve. I know that

If it isn’t clear by this point, I am firmly convinced that if higher education is in the business of selling “scarce” content in an age of Google, MOOCs, and Wikipedia, institutions of higher learning will become obsolete. If our students’ ability is confined to memorized mastery of a subject whose currency is out of date the day they graduate, they are equally doomed. I am also not naïve. I know that