Ideaspaces, January 2020

What is the purpose of a classroom? It is a space where people come together to exchange ideas, to work together, and possibly for assessment. Additionally, we use it as a proxy for campus capacity and, by extension, enrollment. In the latter formulation a classroom is merely a container for student-shaped widgets. While this may offer administrative convenience, it tells us little about how effective the space is as a place for learning. Additionally, the classroom is increasingly understood as part of a larger learning environment that includes informal spaces within the campus and the larger “community of practice” in which a student resides. It is clear that, “learning is an integral and inseparable aspect of social practice.” (Lave and Wenger, 1991, p. 31) To begin to understand how physical and virtual spaces may retard or augment a student’s capacity for learning they must be first and foremost be connected to the idea of social practice and the human processes that ultimately determine success in learning outcomes. As Diana Laurillard argues:

How do we ensure that pedagogy exploits the technology, and not vice versa? A strong theoretical statement about the nature of formal learning, and the requirements this imposes on learning design, enables teachers to make sure they are making the best possible use of the new capabilities on offer. Without this, technology is at risk of being used merely to enhance conventional learning designs, rather than generate designs that are much more effective and innovative. (Laurillard, 2009, p. 6)

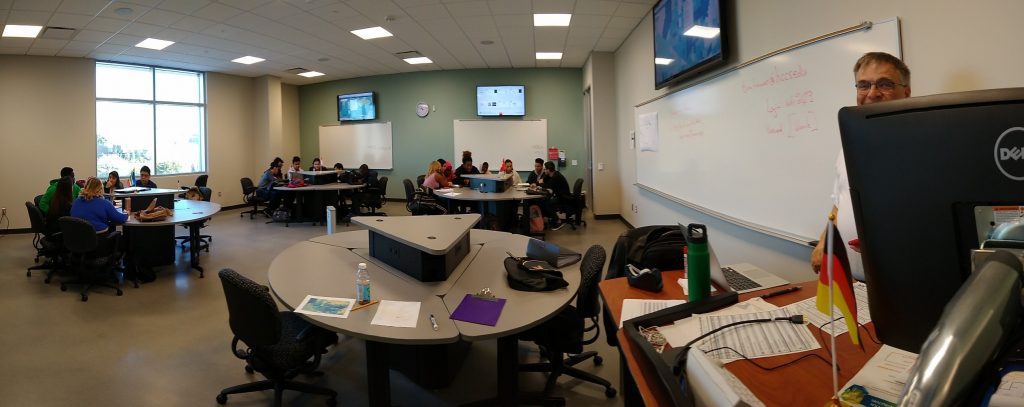

This is not how we usually approach either learning space or technological design projects. Over the last decade I have been involved in numerous campus design and building projects in addition to technological and software adoption efforts. Most significantly, I was the design lead for Houston Community College’s West Houston Institute (WHI), an innovation campus that was a SXSW Learn by Design Finalist in 2018. Over the course of those activities we spent countless hours discussing the number of parking spaces, the size of classrooms, the technology in classrooms, the width of halls, etc. but spent precious little time analyzing the kinds of learning conversations that would occur in those rooms. The same kinds of logistical questions dominated discussions over Learning Management Systems and other software “innovations” that we considered. Any challenges to the learning process would be ironed out through subsequent “professional development.”

This is precisely the opposite approach to what Laurillard is suggesting. Indeed, some innovative features, such as providing mobile furniture in every room, were eliminated or drastically reduced in scope because “most teachers will never teach this way.” This occurred despite the fact that the WHI process, in particular, involved an extraordinary amount of participation and collaboration with a wide range of faculty, staff, and student stakeholders. Even with this effort what was lacking from the discussion was any sort of systematic analysis of the connection between those tools and specific teaching practices. Furthermore, even when this was discussed, it tended to focus on the modality of faculty needs, not those of learners.

These outcomes are not at all surprising. As a political scientist, I am very aware of the aphorism from bureaucratic politics called Miles’s Law, which states, “Where you stand is depends on where you sit.” (Miles, 1978) Even the most dedicated faculty can’t help but to prioritize their day-to-day concerns over difficult-to-analyze student behaviors, especially when confronted by these questions in quick one-off meetings about classroom design. Those facilitating the process have their own sets of priorities, usually centered around budget and project completion.

Furthermore, after working in an architectural practice for a year I recognized how few people in those discussions were even equipped to have that level of conversation about teaching and learning. Extending this to software development, I am often confronted with technology solutions that either don’t address key aspects of active and empowered learning or ignore a suite of unintended consequences. Again, it is difficult to find software designers, many of whom are designing software that is frequently grafted onto a teaching and learning environment after the fact, to understand the intricacies of what makes up effective teaching. This is meant not as a criticism because architects, engineers, software developers, and planners have priorities and challenges that often have little to do with those of the teacher-student relationship. To connect these conversations with teaching and learning technology and learning spaces is asking a lot of them.

A better typology of tools connecting tools to practice when designing and outfitting formal, informal, and virtual learning environments is clearly needed. This typology should be based on a prioritization of active learning and engagement in the classroom. A similar tool analysis should be engaged in with the design of learning management systems. Furthermore, those two tool sets should complement each other so that true hybrid course design utilizing the best of both environments is possible. This systemic approach can both simplify and make targeted design discussions in an era of rapid and fluid technological change.

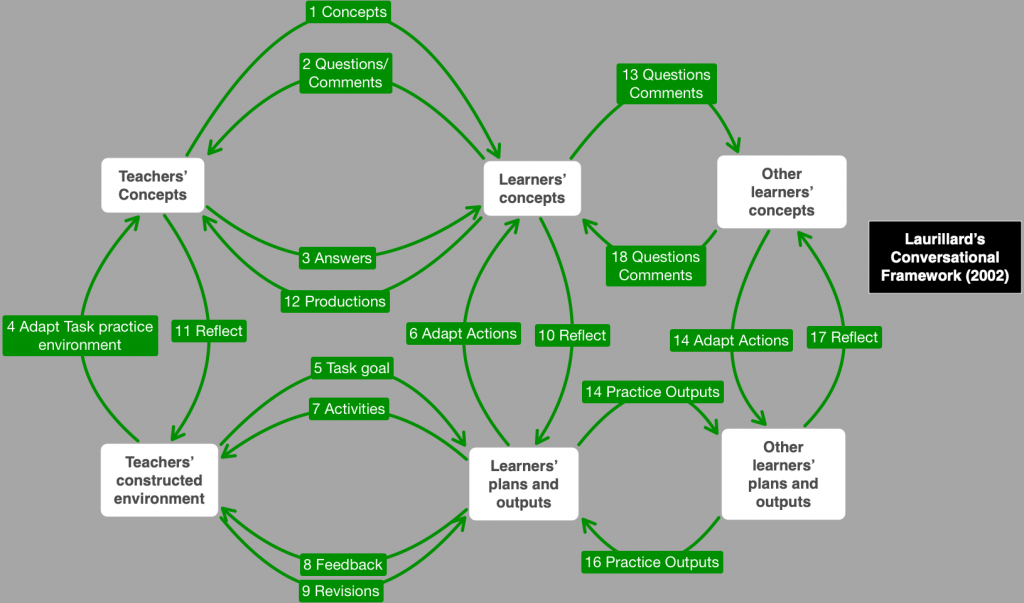

Laurillard posits that learning is a series of conversations between the student and the teacher and among the students themselves. Learner-centered instruction honors these conversations and seeks to make them explicit in order to deconstruct what is going on in them. This is not as straightforward as it may seem as these conversations can be both explicit and implicit (see Laurillard 2009, Darcy 2016). This is because the most important conversation that needs to happen is within the student’s head where new knowledge and understanding are actually constructed (Papert 1980, Papert and Harel 1991).

Learning environments should be treated as sets of tools designed to augment those conversations. At a minimum these environments and their associated tools should not get in the way of effective conversations. Ideally, these environments should be designed to augment the impact of those conversations. These principles should underpin any conversation about design principles in any environment dedicated to learning.

While the modalities of online learning spaces operate under a completely different set of rules than physical spaces do, they still fit within the needs of the conversational framework because in the end the goals are the same, even if you have a different set of tools to get you there. What used to occur in what amounted to the performance venue of a classroom can now be made more persistent and asynchronous as the teacher does not have to be physically present for knowledge transfer to occur. This changes the role of the teacher. Online spaces have the capacity to provide venues for students to come together and work both synchronously and asynchronously without having to physically be in the same place and, as such, changes the nature of peer learning.

There is evidence, however, that online students, particularly those with underdeveloped learning skills (an increasing number of postsecondary students) benefit from having a physical center to their learning experience (Protopsaltis and Baum, 2019). The challenge is that many of those same students also logistically benefit from not having to make a regular on-campus schedule. Approaching this challenge from a pedagogical perspective leads us in the direction of a hybrid environment where the advantages of technology are blended with spaces and technologies explicitly designed to nurture and support human conversations.

From a space and technology perspective, mixing in-person and online education blurs the line between formal and informal classroom spaces. New campuses should be explicitly designed to maximize the symbiotic relationship between online learning and physical support for the online learner. Informal spaces (see the STAC Model) become more important to student outcomes as they give students a place to gather and an environment where college support personnel can assist individuals or small groups of students. Faculty may also want to meet with different sized groups of students to supplement online and hybrid instruction. Consideration should therefore be given to spaces that can be reconfigured as necessary to accommodate different-sized student groups. One idea is informal spaces that can be scaled up to classroom size or alternatively, classroom spaces could also be built with internal dividers to allow group sizes ranging from 10 to 50 students with internal dividers of some sort. Schedule management of these spaces will also have to be adapted to the realities of supporting a hybrid model of teaching and learning.

Conversational Frameworks as a Tool for Visioning Spaces

Understanding how these environments should be configured requires an exploration of connections between effective learner-centered teaching and the tools necessary to carry those out. Laurillard’s Conversational Framework model provides us with a useful roadmap to designing more effective physical and virtual learning spaces.

Laurillard concluded that all spaces should be “productive” environments, which she describes as including “microworlds, productive tools, and modelling environments” in which the learner can “build something,” “engage with the subject,” and “learn how to represent these relationships in some general formalism.” (Laurillard 2003, p. 171). All learning environments, both online and in person, should aspire to be productive environments.

The Conversational Framework is designed to describe the minimal requirements for supporting learning in formal education. It can be interpreted as saying that, on the basis of a range of findings from research on student learning, if the learning outcome is understanding, or mastery, the teaching methods should be able to motivate the learner to go through all these different cognitive activities. In that sense it should be able to act as a framework for designing the learning process. (Laurillard, 2007, p. 161)

Figure 1 Laurillard’s Conversational Framework,

Adapted from http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/10000627/1/Mobile_C6_Laurillard.pdf

Extending “learning design” to the physical and technological tools necessary to carry them out seems like a logical extension of Laurillard’s ideas. Her conversational principles can be unpacked and associated with specific sets of tools. She develops three different sets of actors in every student’s learning environment. They are, broadly speaking, the Teacher, which can include any mentorship role to include tutors, librarians, counselors, and craftspeople in a design environment; the Peer Group, both inside and outside the formal class structure; and, most importantly, the Individual Student. Traditional models of teaching and learning often look at the student as an object, to be acted upon by the teacher or peers. We have constructed learning environments and pedagogical strategies accordingly. This is mistake. Teachers can teach all day long without anyone learning and group work doesn’t in itself equal effective learning. At the end of the day, everything else is just noise if the student can’t or won’t decide to learn.

Independent of these considerations, we have developed a fairly well-established set of standard classroom technologies but often fail to ask deeper questions about precisely what learning modalities they support. Instead, most teachers accept that they have to work with what they are given. These technology packages usually include some form of presentation technology (ranging from overhead projectors to digital projectors to large format televisions) coupled with an interactive work surface designed primarily for the teacher to use (whiteboards, blackboards, interactive displays). Various forms of seating and work surface are provided for the student and the big debate is often centered around how these should be arranged. Design processes that directly involve faculty are considered progressive and, while important, discussions often center on the details of presentation and demonstration technology as this is obviously of central concern to the faculty member. However, as my initial analysis using Laurillard’s tools concludes, these technologies support a specific approach to teaching and learning and can limit the range of pedagogical strategies that can be attempted within a particular physical or technological space.

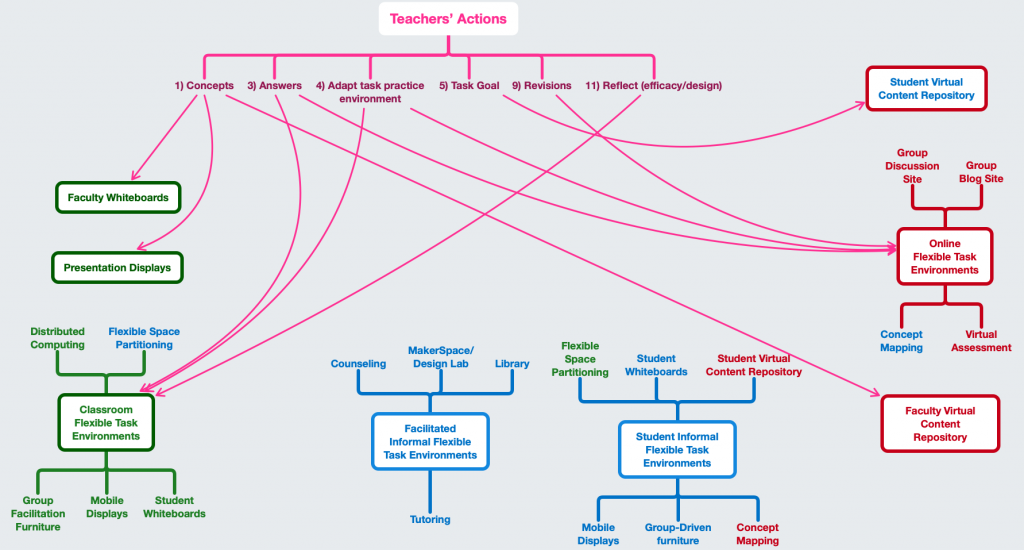

Tools for Teachers

As the traditional drivers of classroom design, teachers present a good starting point for our initial assessment. Laurillard identifies six different actions that the teacher is responsible for in her conversational framework. They are responsible for:

- Providing conceptual frameworks (1)

- Answering questions (3)

- Adapting task practice environments (4)

- Setting task goals (5)

- Ongoing revisions of the instruction as dictated by student needs (9)

- Ongoing reflection of the efficacy of actions and design in the class (11)

Let us look at each of these in turn and discuss how they relate to available tools.

Communicating conceptual frameworks is central to instructionist teaching and follows the same models in structure if not in form (for a discussion of the relative merits of an instructionist versus a constructionist perspective on teaching see Piaget and Harel 1991). To achieve this task the teacher essentially has to have access to broadcast technology. This would include the aforementioned Presentation tools and Faculty whiteboards. Digital tools allow faculty to also create content online for students. Again, content delivery in the instructionist mode has dominated discussion of the relative merits of Learning Management Systems (LMS), textbooks, and related online tools.

The structure of this content is important, especially when it comes to asynchronous, online content. It is much more difficult to produce conceptual structures than it is to simply provide a mass of information that may be hard to connect to any framework. Often faculty rely on their lecture to provide that framework and one of the struggles with online learning has been to mimic that capability without physical presence and immediate interaction. Another issue, both in physical spaces as well as online ones, is that this tends to be the beginning and end of the discussion of learning space and educational technology design (aside from the administrative aspect of “butts in seats”). It is only a small part of the role of the teacher in an effective learning framework, however.

There is a common theme that unites most of the other teacher actions in Laurillard’s framework: the teacher must be available to provide immediate and relevant feedback to student actions. This, in turn, implies the need for various kinds of faculty-led “sandboxes” or dynamic environments both inside and outside the traditional classroom environment. The provision of “answers” is perhaps the simplest of these, but it is important to reflect that the student is ultimately responsible for internalizing and creating their own answers. The teacher can guide this process but he or she cannot make it happen.

Adapting task environments, revising the class, and reflection and design all require dynamic environments that the teacher can reconfigure on the fly to adapt to the immediate learning needs of the class. These can take many forms today. A preliminary list would include: distributed computing, which can be bring-your-own-device or a dedicated computing environment; flexible space partitioning; group facilitation furniture (reconfigurable tables on wheels); mobile displays; and student whiteboards. Finally, modern assessment requires the creation of student product. If this product is to be persistent, an online student content repository is essential to setting fluid task goals (see Knowledge Networks). Fluid learning environments also make it easier to engage in larger semester-level revisions to teaching strategies without having to switch rooms or reconfigure a course shell. If the proper tools aren’t provided to faculty it’s easy for them to fall back on old strategies and practices.

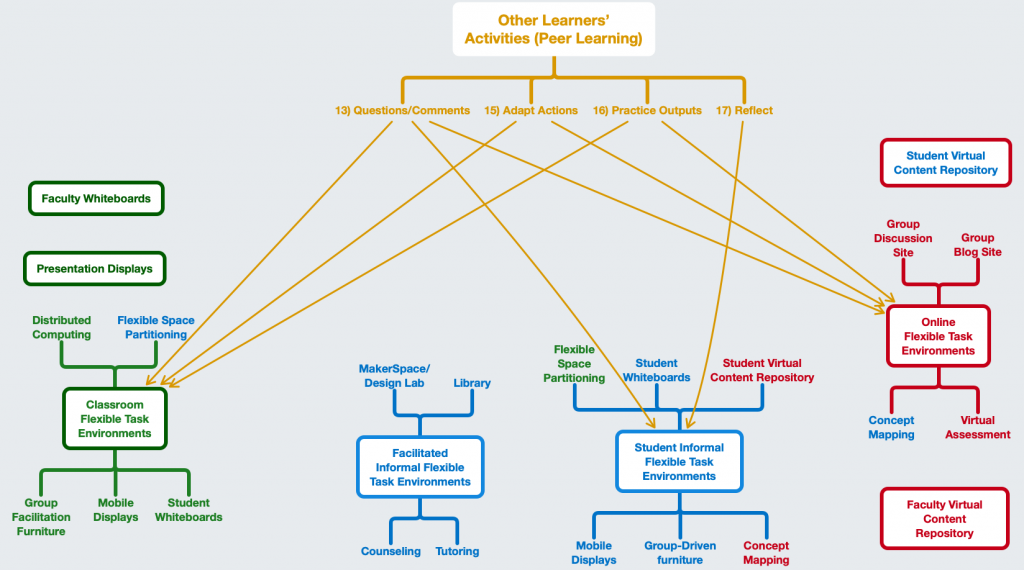

Tools to Facilitate Peer Learning

Peers are essential for effective learning, but they are not decisive. It is important always bear in mind that peers support the individual learning and that group work is an important variable in any learning journey. However, at the end of the day the individual learner still has to navigate the strengths and weaknesses of any group, both formal and informal. Laurillard’s framework makes Peers responsible for:

- Questions and Comments (13)

- Adapting actions (15)

- Practicing outputs (16)

- Reflecting on more formal learning (17)

Peer learning is entirely dependent on groups having the ability to form within formal learning spaces at the direction of the teacher, in informal learning spaces (see the STAC Model), and both formally and informally online. These environments allow groups of students to work together to enrich their learning experiences and to fill in critical gaps that a teacher cannot always effectively plug. Groups also work actively on projects together, providing shared experiences and mutual moral support for teaching and learning. They require a suite of tools and environments that aid them in the development and persistence of their collective efforts.

Peer learning can be critical to student success. Alexander Astin engaged in a study of almost 20,000 students in the 1980s and concluded that, “The single most powerful source of influence on the undergraduate student’s academic and personal development is the peer group. In particular, we found that the amount of interaction among peers has far-reaching effects on nearly all areas of student learning and development.” (Astin, 1993, p. 7) If it is difficult to from and reform groups peer conversations, particularly in commuter schools where student persistence on campus is a challenge, don’t happen. This is also a serious barrier in online learning where the structure of most LMSes tends to silo student learning rather than bring them together. In order to enhance the learning of the individual, group tools also must facilitate spontaneous interaction and enhance the persistence and sharing of ideas and concepts.

The Needs of Individual Learner

At the center of Laurillard’s model is the individual learner. Teachers and peers form important supporting networks for the individual’s learning but at the end of the day all teaching and learning must be tailored around the needs of the individual. Groups can form, teachers can teach, but in the end only individuals can learn.

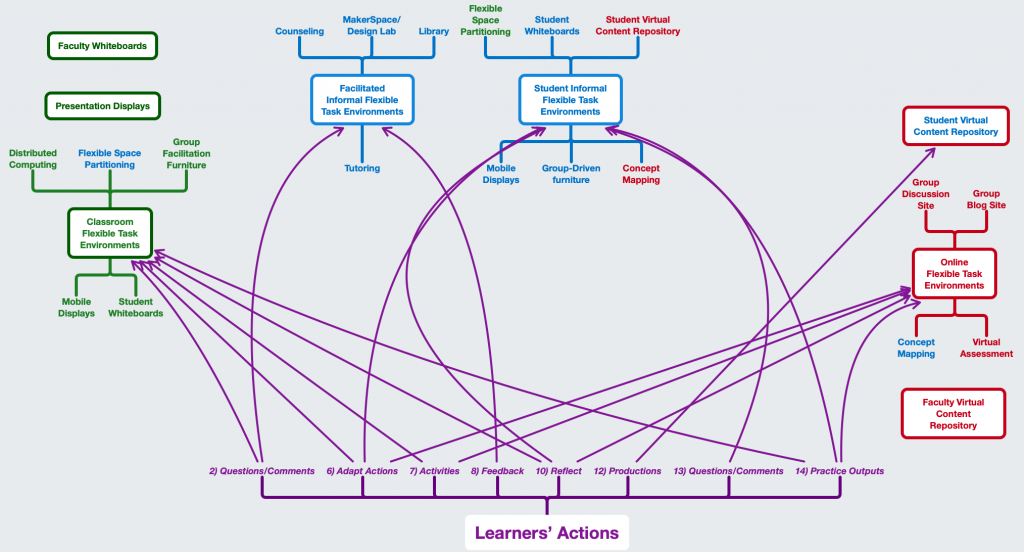

The learner has eight important roles to play in his or her learning journey. He or she must:

- Be able to question and comment on concepts and processes introduced by teachers (2)

- Be facilitated in being able to adapt their actions around making themselves better learners (6)

- Have access to activities that enrich, enhance, and augment their intellectual growth (7)

- Get feedback on those activities (8)

- Be given time to reflect an internalize new information and skills (10)

- Be given tools to produce learning objects (12)

- Be able to question and comment on concepts and processes introduced by peers (13)

- Have environments where they can practice outputs of their learning activities (14)

Five of eight of these activities require access to flexible learning task environments, both virtual and physical. These activities involve everything from having experimental spaces to play with ideas until they are understood to having spaces to congregate with peers both online and physically in order to work through problems collectively. Facilitated environments also come into direct play as learners need on-demand feedback and help across a range of activities ranging from content mastery (tutoring and faculty access) to information literacy (library) to work/life balance (counseling) to design (making).

Physical spaces, coupled with scheduling and people resources, are critical to meeting the needs of individual learners. Extended hours of services may be needed especially if students are receiving a significant portion of their instruction online. Finally, learners need a variety of production environments to create their educational products. These production environments used to go no further than the typewriter but in the digital age should also include makerspaces, web development and digital repositories to house and share an increasingly diverse student work product.

Preliminary Analysis and Conclusions

Preliminary analysis of student needs using this model leads us to some basic design guidelines:

- Student work areas and surfaces need to be given priority both inside and outside the traditional classroom environment. This means:

-

- Ubiquitous computing

- Copious and mobile whiteboard space in both formal and informal learning spaces

- Mobile display technology that can used to interface with virtual environments

- More student control over virtual spaces such as the LMS or other online work areas

- Students need to be given as much agency in the configuration of spaces as possible. This means:

- Mobile furniture and partitions

- A variety of spaces where students can congregate

- The ability to spontaneously form groups within an LMS or other virtual environment

- Teachers need to have a high level of control over their classroom spaces to accommodate for different kinds of classes (traditional and hybrid) and learners. This means:

- Classroom furniture must be as flexible as possible

- Student work areas must be maximized

- Classroom size may need to adjust to the needs of different modalities of hybrid learners – some classrooms may be blurred between traditional “formal” and “informal” areas

- Student interaction modalities such as simple, on-the-fly videoconferencing should be prioritized in the design of online courses and software

It is sobering to note how little time is spent in either physical or online space design facilitating conversations between teacher and learner driven by the learner. The result is that the student can feel isolated and disconnected from the learning experience, leading high rates of failure or dropping out entirely. We have talked for years about “meeting the student where they are” but more often than not we have to struggle to overcome barriers to genuine conversations, both in-person and online. Given the number of students most faculty have to deal with, it is easy fall into the “people management” trap and our spaces are conducive to that kind of approach. Mass higher education doesn’t have to mean widget-based education and, indeed, we have found that to be incredibly destructive to learning. We have at our disposal a vast range of tools that can allow us to connect in meaningful ways with students at a scale not possible even a decade or so ago. It is time to prioritize connection in our design of the spaces where those connections are supposed to occur to effective pedagogical frameworks.

CITATIONS:

Darcy, Damien, Learning Design in Hybrid Spaces: Challenges for Teachers and Learners (University College of London, Dissertation, 2016)

Laurillard, Diana, Rethinking University Teaching: A Framework for the Effective Use of Learning Technologies(London: Routledge, 2002).

Laurillard, Diana, “Pedagogical forms for mobile learning: framing research questions” (2007) at http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/10000627/1/Mobile_C6_Laurillard.pdf.

Laurillard, Diana, “The Pedagogical Challenges to Collaborative Technologies,” Computer Supported Collaborative Learning (4/2009), pp. 4-20.

Lave, Jean and Etienne Wenger, Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

Miles, Rufus E., Jr. Public Administration Review Vol. 38, No. 5 (Sep. – Oct., 1978), pp. 399-403.

Papert, Seymour and Idit Harel, “Situating Constructionism” in Papert and Harel eds., Constructionism (New York: Praeger, 1991).

Papert, Seymour, Mindstorms (New York: Basic Books, 1980, 1993)

Protopsaltis, Spiros and Sandy Baum, “Does Online Education Live Up to Its Promise: A Look at the Evidence and Implications for Federal Policy,” at http://mason.gmu.edu/~sprotops/OnlineEd.pdf