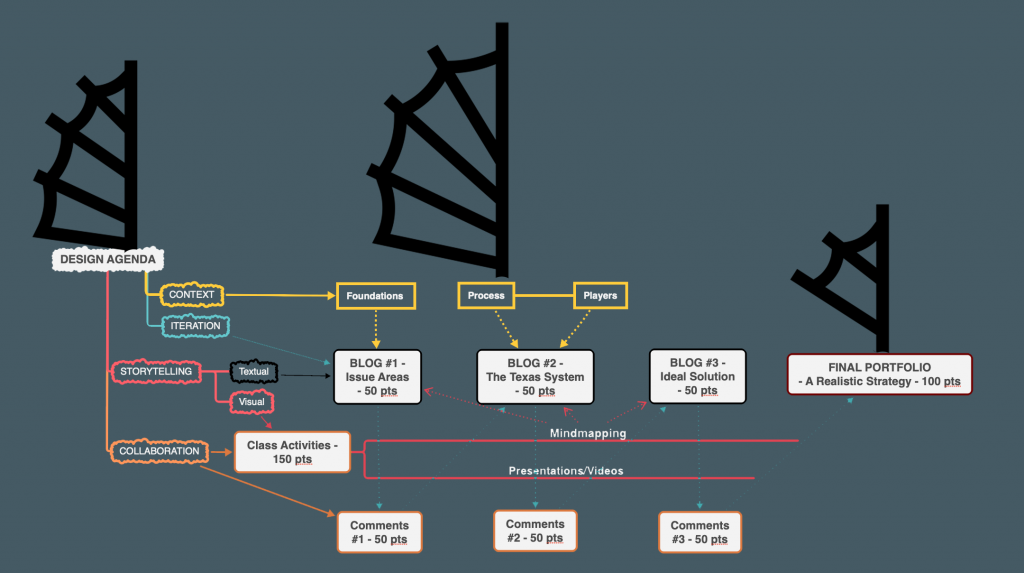

Over the past year I have been exploring ways to create greater meaning, empowerment, and, ultimately, motivation in my students. Last year I reoriented my government classes to try to focus more on issues the students cared about instead of starting with the content trying to shape it toward student interests. A key element in this strategy introduced transparency into the process in order create a different atmosphere in the class focused more on the skills necessary to acquire knowledge instead of spoon-feeding them arcane knowledge about American and Texas politics. I classified these skills into three broad groups: Iteration, Storytelling, and Collaboration. To this I added a fourth category to continue to inject content into the class. This Contextis necessary to inform the exercise of the other three skills but it takes a secondary role to the three aspects of the class that I thought will have the most lasting impact on my students.

Iteration, Storytelling, and Collaboration have always been a part of my instructional method. My classes from the beginning of my teaching career focused on iterative writing assignments over the course of the semester as a way of assessing the growth (or lack thereof) of my students’ critical thinking skills. Of course, the act of writing is in itself a basic form of storytelling. Collaboration was initially in the form of simulations and other interactive exercises in class, but it often took the form of enrichment rather than as a central component of the learning process.

In the latest iterations of the class I have completely refocused the class around these skill sets. This requires some preparation of student expectations because it is very different from most of the classes they’ve been taught, whose primary purpose was content delivery. I start every semester asking my students to reflect on why they are in college and what they thought it was preparing them for. I then introduce the idea that the world may be shifting under their feet even as they prepare to meet its challenges. I do this in different ways but one of more effective means is through the use of the video “Humans Need Not Apply” from 2014. We then have an extensive discussion over the contents of the video and then relate it back to their own learning journeys and aspirations.

Most students have never reflected on their learning in this way. They’ve just done what they were told. According to Winkelmas et. al. (2016), this kind of process transparency can be a key to student success. “Faculty noticed increases in students’ motivation in class, higher-level class discussions with sharper focus, more on-time completion of assignments, and fewer disputes about grades.”

Transparency and Iteration

Transparency poses fundamental challenges to the toolsets and mindsets that most instructors have to work with. First all, most of the tools we have to work with often equate collaboration with cheating. Their design inevitably silos the way that students work in the name of academic integrity. This neatly ignores the fact that learning is a communal process as much as it is an individual process. New ideas and inspirations come from your peers. Creative approaches to problem solving are heavily dependent on context and that context is provided by the network of ideas a thinker resides in. And yet, our tools, from tests to the very structure of Learning Management Systems, are fundamentally designed to keep students from seeing what their peers are working on. This poses severe challenges to collaborative, design-based learning, not to mention the negative conditioning it imposes on our students’ mindsets.

Iteration and transparency are enhanced by extending the classroom community beyond the walls of the physical meeting space and technology should facilitate this, not impede it. Therefore, I bypass most of these tools in favor of old school Web 2.0 tools such as WordPress, which I use for collaborative blogging and commenting. All work in this class is visible to the rest of the class and to the world at large. Students are allowed to adopt anonymous handles in order to protect their individual privacy but their work, both in class and out of class, is very much a part of a collaborative whole which integrates all four elements into a semester-long design project.

Only part of their grade (150 out of 500 points) are the blogs themselves. An equal number of points are earned by the students commenting on each other’s work. To assist me with showing the students how to effectively communicate with each other I use Emily Wray’s RISE Model, which is a simplified version of Bloom’s taxonomy. Comments are assessed based on the level of thought put into them. At the base level is Reflection, which is simply a reaction to some point in the blog. After that is Inquiry, which is the same but with additional information in the form of a source that either expands the blog author’s points or provides a point of contention. Finally, there is Suggestion, which requires the student to take a passage from the blog, rewrite it to make it better in some way, and to provide a source to support the improvement. Suggestion forces the students to actively engage with the blog in a way that they are unused to and often provides some good teaching moments as we discuss these in class. The Elevate part of the RISE model is reflected in the blogs themselves, as well as the Final Portfolio assignment (100 points).

Integrating Storytelling with Design

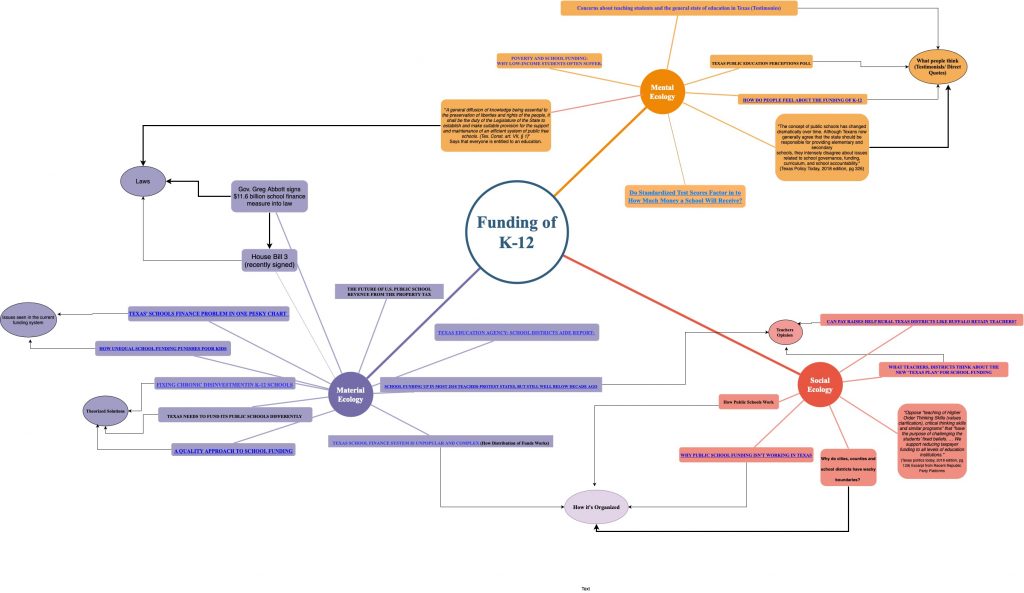

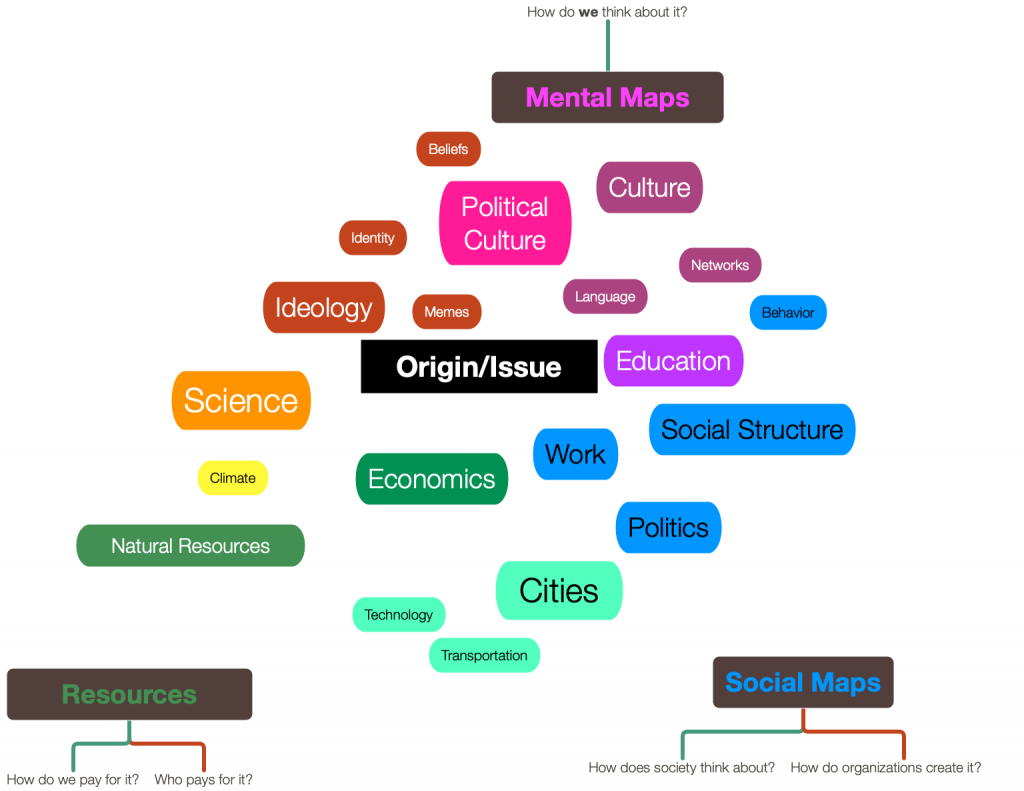

All of the iterative efforts of the class are focused on developing higher level analysis and storytelling skills. Original storytelling is often a difficult concept to master, especially when you start introducing the wide variety of storytelling tools the students have access to. As I have discussed elsewhere, visual storytelling is critical to modern problem-solving and is underserved in most academic contexts and this remains a challenge in this class. What I have introduced into the class most recently is the idea of concept mapping. I use draw.ioas a platform to create a basic template to allow the students to start to build visual stories.

These stories require a framework and for this I have turned to Alex McDowell’s world-building mandala. McDowell, a production designer known for his work on movies such as Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report, has developed a schema that can used to construct mental models for creating conceptual worlds. While originally developed with moviemaking in mind, McDowell’s Mandala is a useful roadmap for looking any universe of problem sets and to encourage solution building using emergent design principles.

One of the challenges that McDowell manages to illuminate through his process is the non-linear nature of narrative. We have been trained by text and traditional cinema to understand the world through the lens of the “Hero’s Journey.” In this paradigm the world only matters from the perspective of the hero. Context is only important for the immediate needs of the main characters. McDowell’s (and Spielberg’s) breakthrough in his design of Minority Report was to create the world and then force the hero to operate within its contexts.

We all instinctively know that the Hero’s Journey is an invented narrative but what we don’t realize is that it perverts our thinking about complex problems. “Journey” implies a beginning, middle, and end. Instead, today’s problems, from democracy to climate change to education itself are complex universes of challenges and are never-ending stories. They exist within larger contexts and are fundamentally creatures of those contexts. I want my students to grasp the larger implications of the design challenges they are working on and to translate those complex political, social, and economic environments into coherent narratives. McDowell’s mandala provides a critical template for deconstructing issues and then constructing stories within their larger contexts. Storytelling is critical to any design process, but it has to be taught in order to be effective, and appropriate tools should be employed to facilitate the storytelling process in service of the design process.

Basic Politics World Building Mandala Based on McDowell (2015) at https://bit.ly/31BCJtt

Using McDowell’s world-building mandala as a basic format, students are asked to plot various articles from their selected issue areas as well as areas from their exploration of concepts of government on the template. These, plus student-accessible whiteboards form the key “workspaces” for collaboration. All technology usage in this class is closely aligned with the needs of the three skills. In this case technology is designed to assist students in being able to collectively tell stories. The online concept map is effectively a group workspace, as are the in-class whiteboards. The use of WordPress as a class-wide collaboration and presentation space is the final piece of this storytelling puzzle.

The students are assigned a design challenge based on their interest, which we collectively explore during the first couple of class sessions. The purpose of this design challenge is in part to develop a semester-long narrative for each group of students. In most iterations of this class three groups have emerged. In my Summer I class, the first group explored how we could design a more equitable and effective school funding mechanism in Texas, which suffers from chronic inequality between richer and poorer school districts. The second group explored how we could increase voter participation, particularly among currently underrepresented groups, in Texas, which has among the lowest rates of voter turnout in the country. The final group explored how we can get more people onto health insurance in Texas, which has one of the highest rates of uninsured in the country.

The blogs align with this design process. The first blog asks the students to give the landscape of their issue area in order to understand the key challenges that exist there. The second blog asks the students to explore Texas government for explanations as to why these issues have not been addressed. The third blog asks the students to explore other states’ programs in their areas and to imagine some realistic best practice outcomes for Texas. For the Final Portfolio the students are asked to map out a strategy for moving the ball forward and advocate for their solution using a website as their tool.

Students at Work on their Concept Maps

The storytelling aspect of the class is constantly reinforced through a series of interactive exercises where the students are asked to review and assess each other’s work. Toward the end of the semester, I ask each group to create a Google spreadsheet that summarized each person’s three blogs as a first step towards developing a set of strategies for the Final Portfolio. This shared document is a workspace that assists them in understanding how all of these stories could be leveraged in their final work. It also forces them to reflect on their own and other’s work and how that contributed to their Final Portfolios.

One of the challenges to the iterative storytelling aspect of the class is that students are not used to going back and reviewing their own work, much less anyone else’s. Creating the commenting structure does not resolve this issue because comments were often done in an off-handed, check-box manner with little regard for their actual utility. Additionally, I quickly discovered that the authors of the blogs rarely took the time to read the comments on their own work. I now force the issue by having the blog owners do an initial assessment of the comments on their own blogs using the RISE model.

Integrating Collaboration into the Process

Like iteration, collaboration is designed to reinforce storytelling and design. Most of the work in class is collaborative in nature. From the beginning of the semester students are required to bring in sourced ideas that are plotted on the group mandala in class. Periodically, the groups are asked to report out on the development of their mandala to the rest of the class. Blogs are also written based on the connections and stories that emerge from the concept maps. Most of this work is done in-class as a group activity. I circulate through the groups to monitor the course of conversations and challenge their assertions and ideas and provide suggestions for further inquiry. Interspaced with this brainstorming activity are brief introductory lectures for each section as well as some activities designed to illustrate basic concepts. I encourage their inquiry to push them to dig deeper into particular aspects of Texas government.

Getting the students to collaborate is not a given. They have been trained by the industrial education system to work alone. Therefore, most collaborative work is perceived as, at best, an adjunct to individual work. Group grading is a challenge as assessing who is pulling his or her weight in the group is a particularly difficult issue. Therefore, I rarely assess the group as a whole and if I do it is based on in-class work where I can take an active role in making sure students are participating in the discussions. I have used group assessments for some of the in-class activities in the past but I have increasingly seen that there is little real utility in this. Active teaching strategies are much more effective in eliciting curiosity and effective use of classroom time. The effectiveness of group work directly leads to the outputs on the blogs, which, while individual work, are based on a foundation laid by group discussion and work.

Assessment

My grading strategy has evolved away from qualitative assessment a great deal. As I discussed in a blog earlier this year qualitative assessment can actually be disempowering as it involves a god-like judgment from on high. I try to demystify this as much as possible by providing clear rubrics around what constitutes different levels of work. However, at the end of the day, it’s still my judgement, especially at the higher levels, as to whether they are working at the specified level or not. A large portion of my grade these days tries to avoid this problem. Only 50% of the points in my class come down to qualitative assessment. Instead, I assign points to students based on the work done. They either complete it or they don’t and it’s the natureof the work that determines whether they get the points or not. This is where RISE model comes in handy. If students demonstrate the ability to work at the Suggestion level, they get the higher level of points. The activity itself is the meaningful part of the grade. You either do it right or you don’t. Your points are a reflection of whether you did it and not how well you did it.

In-class activities are based on a similar model. The students get 5 points for each relevant source or citation they bring into class (they have to explain why it’s relevant to get credit). These sources form the basis for the concept maps, which in turn produce the blogs and Final Portfolio. I don’t grade the concept maps. I grade the product in terms of storytelling that emerge from the concept maps. The 120 points that earned from these sources are subject to reduction if students are not attending class so they also reflect their purpose as laying the groundwork for in-class work.

Outcomes

It is extremely hard to address preliminary outcomes given the extremely small sample sizes (N=18) and comparing summer students to regular term students is often difficult given the respective populations of those students. During the summer the community college tends to attract better prepared students as transient students from 4-year schools often return to take a class or two and better-prepared dual credit students take classes along with the general population. This class also has some marked difference in the character and preparation for assignments that could also impact results positively.

Initial results, however anecdotal, are encouraging. Out of 18 students, only one student dropped the class and only two failed. Feedback from the students over the experience was very positive as this strategy made a nebulous concept (government) very real as they worked their way through the problem-solving required of any design challenge. I found I spent most of my teaching time making sure that their solutions were realistic, and this constant challenging seems to have paid dividends. In the initial qualitative assignment, the students’ first blog, 65% rated either A or B work. In comparison, the most comparable class from last Fall had 40% getting either an A or B on the first blog. Again, I have to be exceedingly cautious about the numerical results, but I have noticed an improvement in the students’ ability to synthesize information into new narratives, which has always been one of the toughest challenges, even with the best students. This is because most of them are so embedded in the read and regurgitate model that the idea of creating something new is a struggle for them. The concept mapping approach seems, anecdotally at least, to have improved their skills in this area.

A well-designed class should enhance their own personal learning in exactly the same way as it teaches them to explore content-related challenges and develop the necessary skills to become lifelong learners, whatever path they find themselves on. Being able to alter and adapt conceptual paths will be critical in a world characterized by rapid and unpredictable change. Ann Pendleton-Jullian and John Seely Brown call this a “whitewater world” in Design Unbound and reflect that, “Doing and seeing differently means that we can begin to interact with and experience the world differently. A new twenty-first century ontology is emerging.” (Design Unbound, MIT Press, 2018, p. 29). An active transparency strategy that focuses on teaching the ability to iterate, make sense of complex stories, and leveraging knowledge communities will prepare our students for the widest range of possible futures.

Some of my other recent reflections on Empowered Learning:

- Moving from textual thinking to visual thinking – eCampus News, June 5, 2019

- How power dynamics can undermine effective learning – eCampus News, March 7, 2019

- The biggest barrier to deconstructing education is not money – eCampus News, January 29, 2019

- Leveraging Transparency to Create Zones of Empowered Learning in Traditional Systems – FOEcast Network, August 2018