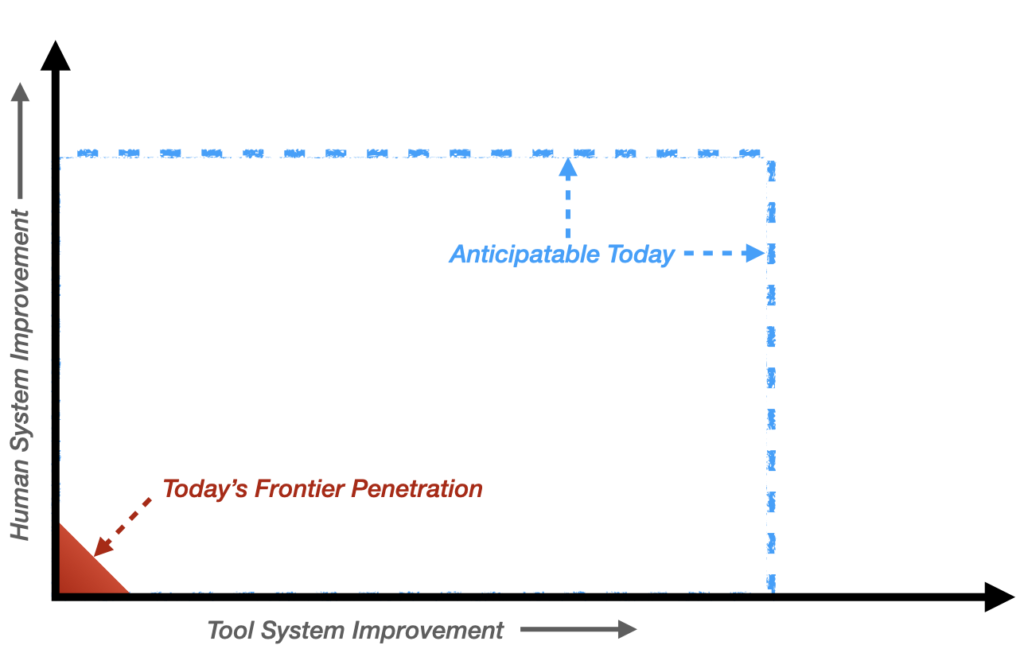

Tools should not drive our activity. Tasks should. Tools should expand our ability to execute tasks. They should give us more time to escape routines and concentrate on the activities that make us more human and escape the dehumanization of our industrial education systems.

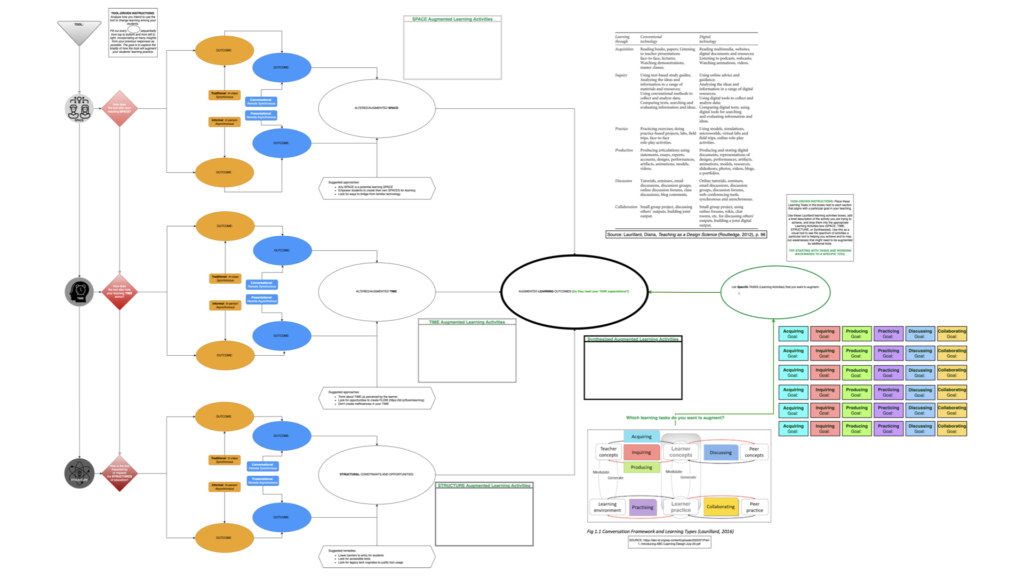

In September 2022, the Shaping EDU Community released its EdTech Jetpack. Over the last year, the Toolset Group within ShapingEDU has held several events that focused on understanding the relationship that tools have to our tasks. This seemed like an opportunity to me, so I blended the work of the Toolset Group to build a template tool to analyze how those tools might reshape our practice. I call it the “Tool Augmentation Tool (TAT).” (A comprehensive guide to the TAT can be found here.)

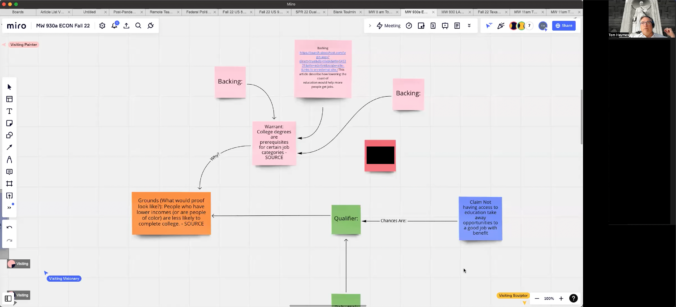

To use the tool, simply go to https://bit.ly/toolaugmentationtool, hover your cursor over the bottom and select the pencil (edit). This will download an editable copy to your desktop. You will need to either download the Diagrams.net app or upload the file to their online app. Here is an example analyzing a tool I use a lot in my classes: Miro.

(The TAT is an iterative design. If you have any suggestions on how to improve it, please don’t hesitate to reach out to me at tom@ideaspaces.net.)

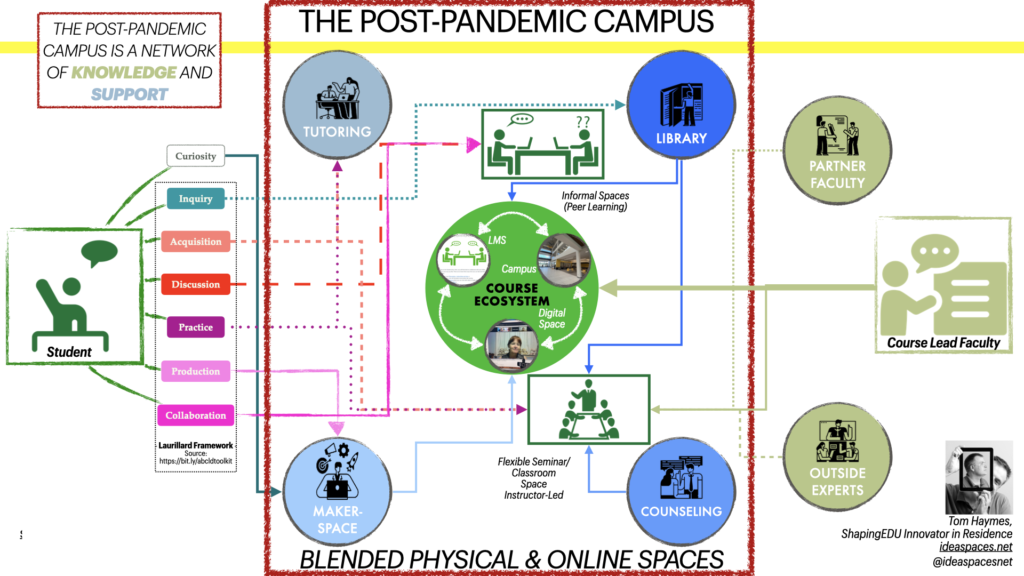

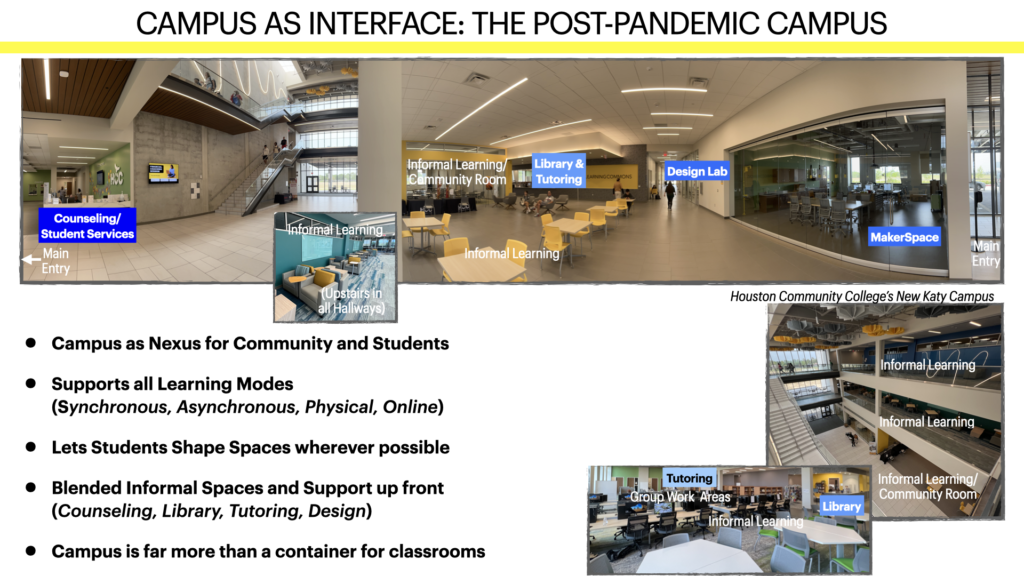

Over the last 20 years, but particularly in the last five, we have run up against the limitations of the mass education model. To achieve scale during the massive growth of education in the 20th Century, we built systems that subsumed the fundamental humanity of the learning process. If learning is a human process, teaching should be a human process. All too often, however, we bury teaching under the economics of mass education. Many of the tools we use on a day-to-day basis facilitate outdated systems whose function was scale, not individualized learning.

The goal of the Toolset Project has always been to break through dehumanizing systems of learning and strategically employ technology to humanize interactions with our students. We continue to see the imaginative use of tools by creative teachers to mitigate the effects of these systems. While this does not excuse us from the need to reform systems, most teachers struggle to change the larger learning ecosystem in which they work.

On the other side of the equation, we have seen an explosion in the options we have available to us as teachers. However, constraint is a key driver of creativity. The Tool Augmentation Tool introduces an element of constraint as we evaluate how tools actually reshape the environments we teach in.

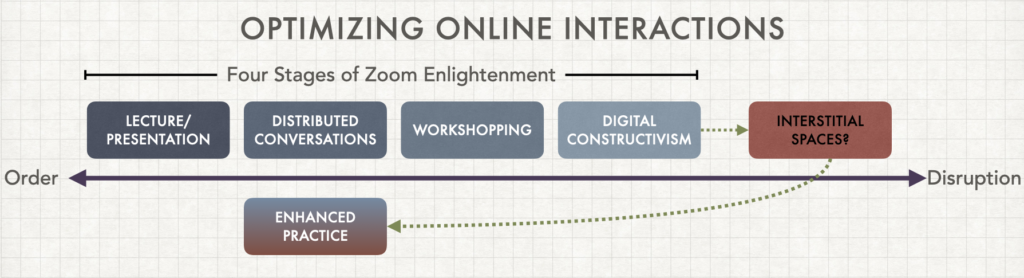

When the pandemic hit, it created a range of constraints most teachers had never considered before. I used my experience from distance education failures to reimagine what kinds of tools I could pick from to reach my students remotely without robbing them of their humanity.

The importance of synchronous communications was glaringly obvious. The need to develop communities of practice and learning was undermined by the distance between the members of the community. Without community, we are not humans. Without community, growth is very difficult. A primary function, therefore, of every tool needs to be its ability to grow community. Connecting people is why we built the Internet.

Shared understandings strike at the root of what we are trying to create as teachers. The keyword there is “shared.“ You can’t share if there isn’t a community of trust in which to do it. You build trust by playing and with carrots, not sticks. Our tools should therefore facilitate play. Our incentive systems should be based on mechanisms of growth, like formative assessment, and our tools should facilitate that.

There is a whole suite of tools that claims to help us achieve these goals, but we must assess them carefully, using an understanding of how our communities of learners come together and pulled apart.

The TAT breaks down this key aspect of our learning environments. It asks how they create or undermine communities of practice. It is the tool that should run the gauntlet, not the teacher and not the student. In order for that to happen, we must assess the tools based on the needs of the learner and the teacher, not what the tool dictates.

As you work through filing out the ovals, ask yourself how the tool being analyzed facilitates or undermines community in the modes of interaction. Some tools may be powerful under one set of circumstances and destructive under another. The aim is to consider the tool under the broadest set of lenses possible.

To achieve this, we break down how the tool will affect or is affected by the three levels of the IdeaSpaces Framework. This should allow us to isolate its effect on specific parts of the learning environment.

- How does the tool change the space?

- How does the tool expand the time available for learning – a key constraint on every learning process?

- How will the tool interact with the industrial structures that most of us have to work within? (Or, if you were fortunate enough to have control over those constraints, How can you use the tool to reshape the larger context in which students have to learn?)

The second step is to assess how the tool alters the four different places where learning takes place.

- Is it primarily focused on augmenting what you can get done in a physical classroom?

- Is it primarily focused on expanding the range of possibilities available during synchronous online conversations?

- Is it primarily focused on enhancing the students’ ability to teach each other through informal learning?

- Or is it primarily focused on enhancing the students’ ability to create artifacts of their learning that they can bring back with them to the community?

Any tool might enhance all four modes, but it’s important to consider how it does. Every tool and every mode interacts with the space-time-structure environment in which your learning experience takes place.

The degree to which any mode interacts with any IdeaSpaces level will differ, but it is a useful thought exercise to analyze how each of them might be impacted by the tool you are interested in applying to your teaching.

Once we have deconstructed the effects of the tool, we can blend them back together to create a holistic view of how the tool is likely to change the environment in which our students learn. It may give you new insight into how we might use the tool. It may highlight key weaknesses of the tool you are considering, causing you to discard it entirely or change how you’re planning on implementing it.

Used correctly, the TAT should give you a richer perspective on how you might use the tool. It also provides a mechanism with which we can share these insights with others. (Hold on to your maps and stay tuned.)

The sharp-eyed among you will have noticed that the Tool Augmentation Tool is a conceptual palindrome. We can also run this exercise backwards by creating a set of tasks we want to do, or we want our students to do, and then plugging in a set of tools to achieve those goals. We can also explore the template from right to left and then use that to imagine what kind of tool would fulfill your needs based on that assessment.

As teachers we are all constructors and creators of worlds. An essential challenge to all teachers in the current fluid post pandemic environment will be how we construct new realities based on what we learned while teaching during a time of extreme constraints. The Tool Augmentation Tool can serve as a map for navigating our complex digital environments. Ultimately, we can use it to construct whole new worlds of teaching and learning.