Our lives are narratives. We tell stories to learn from ourselves, to learn from each other, and for others to learn about us. A common theme emerged from the discussions at last week’s Mini-Summit on Emerging Credentials and Future Employment: Our credentialing systems’ signaling limitations distort the stories of what we’ve learned, what we do with them, and how we portray ourselves to those who might want to work with us. Our stories about ourselves are not getting where they can help us the most.

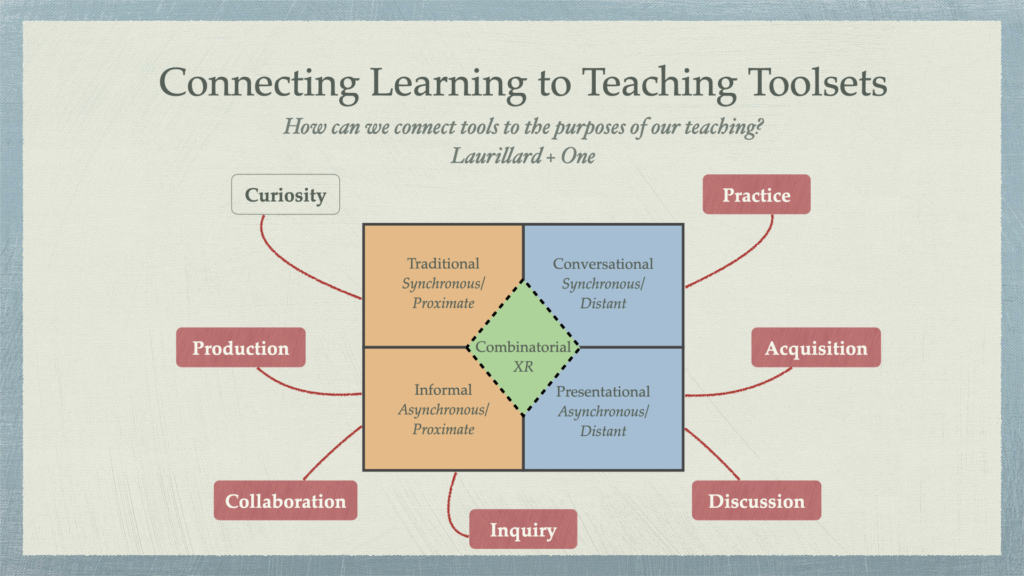

The goal of credentialing of any sort is to communicate achievement in learning (and doing) to potential employers as richly as possible. A basic tenet of the IdeaSpaces approach to technology is that we must always start with our goals and then work backwards to add the tools (technology and structures) necessary to achieve those goals. This is an iterative process, constantly looking at the technology environment to grasp new opportunities to augmenting our progress toward achieving those goals. Our tools and systems for communicating achievement at scale have never been good at telling rich stories and are long overdue for a re-examination.

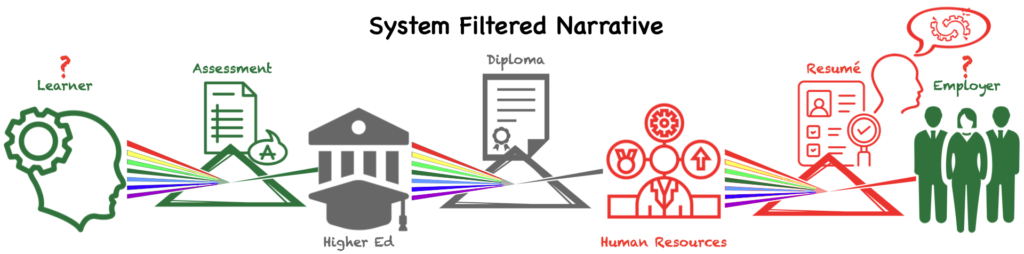

Industrial systems of credentialing depend on cumbersome systems because the technology that they are based on, mainly paper, is an inefficient way of communicating the richness of an individual. It can be done, but the skill necessary to be a great writer/autobiographer is beyond the capabilities of most of us. Therefore, we’ve had to rely on shorthand representations of achievement that start with grades and assessment and “end” with diplomas, degrees, certificates, and resumés.

On the other end of this process, employers need high-quality employees. Once they exceed their immediately known talent pool, they have had to rely on abstractions of people to assess whether they will make meaningful contributions to the team. There is a reason that the best way to get a job has always been to know someone where you want to be hired. These shortcomings matter less for simple jobs than for recruiting innovative and creative talent. The needs of most employers are trending more and more to the latter category of worker.

Current industrial, paper-based systems of signaling create systems of connecting learning with employment. Their narratives are distorted by the mechanics of processing figurative and literal paper through normative structures. Richer canvases are available to us in the digital age. The signaling tools we have should reflect the richer learning journeys we experience in the digital age.

Iterating how we represent the data of our personal achievements is essential for relating the rich universe of ways we learn today, most of which are through informal learning. To cite just a few examples, we learn from YouTube videos, making, massively open online courses, or just by engaging in conversation within a distributed network of thinkers like ShapingEDU. These are not just passive exercises. It is possible to tell our learning stories through practical artifacts across a wide range of platforms, including videos, websites, and blogs. Learning is more transparent than ever before in human history because of these tools. Most methods of achievement signaling don’t use them.

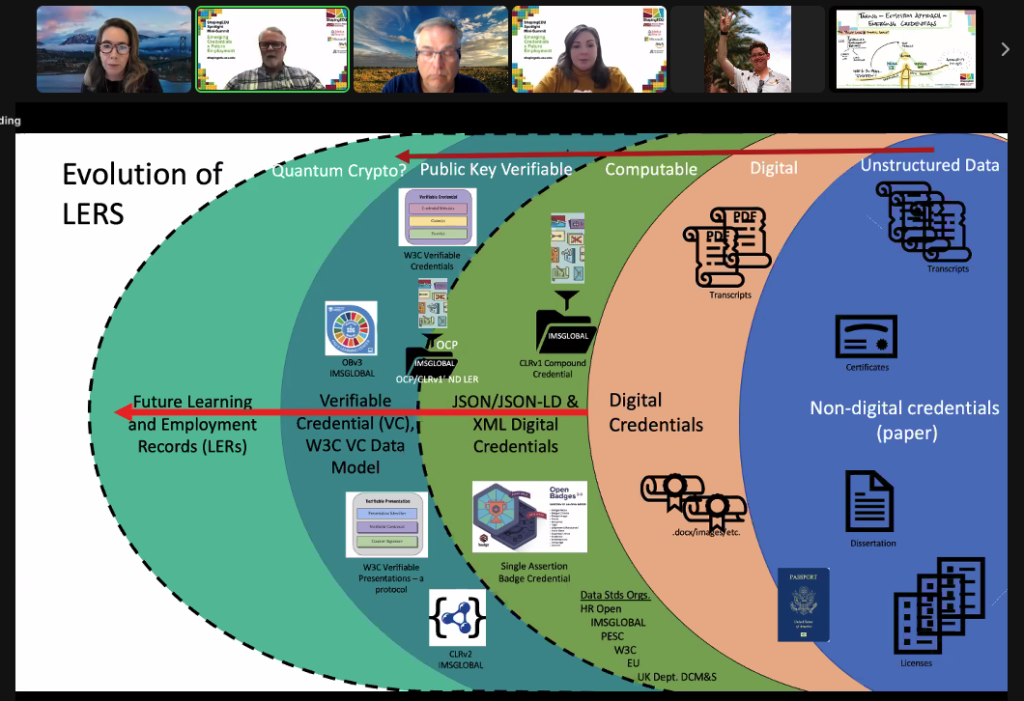

The defining characteristic of the digital age is information plasticity. Data can be shared, remixed, and combined because it is digital. The success of micro-credentialing will depend upon its utility for creating a tapestry of digital stories that connect learning, credentialing, and employment better than legacy systems. Phil Long gave us a compelling illustration of what was possible in a world of digital stories when he described the Learning and Employment Records (LERs) Project he has been working on.

Our systems of schooling are only gradually grappling with these emerging realities. All systems are conservative tools. We build them to organize behavior for efficiency’s sake. We developed most of our systems of education during the industrial age, when the model was to transfer the efficiencies of the factory floor to the emerging information industries. Learners became widgets. The lubricants were the streams of paper that accompanied them at every step.

Industrial logic is deeply engrained in education’s information structures. These systems may have been computerized, but this has simply digitized paper rather than replacing it. Paper-based data streams create barriers to the richer narratives made possible by truly digital systems. Smaller bits of learning are lost. “Achievement” is expressed in the shorthand of degrees, transcripts, grades, and exams.

The third part of the story involves yet another disconnected set of systems: employers. We like to think of the market and private enterprise as being flexible and subject to easy change. The conservative nature of structures doesn’t change just because they happen to be in the private sector. Whether you are talking about education, government, or private industry, structures find efficiencies through routinization—often based on paper. The gatekeepers of employment are the human resources department. Their primary concern, and what drives them in their tool selection, is dealing with a daily deluge of paper equivalents. It is a defensive battle and defense makes for particularly conservative structures.

These systems add another narrative disconnect between learning and the ability of employers to perceive what potential employees can bring to the table. What is a better reflection of my ability, a resumé and cover letter or the rich tapestry of artifacts that I have built and shared?

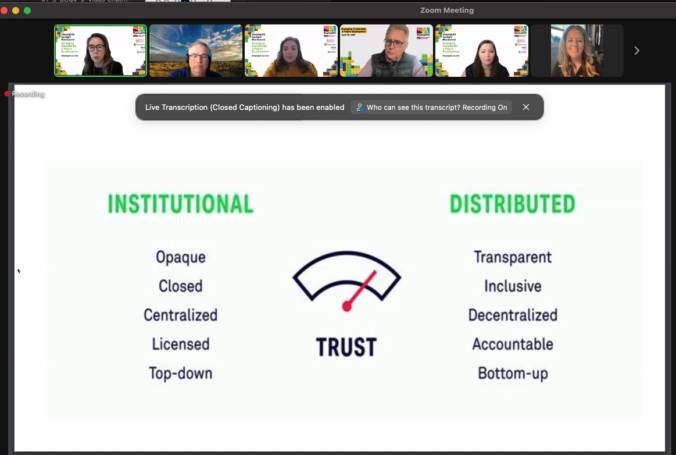

We find ourselves caught in the gears of multiple anachronistic systems based on industrial principles and predicated on the technology of paper. The thing that keeps these systems in place is their perceived legitimacy. As Cheryl Grant pointed out in her presentation, the strength of new forms of certification being proposed lie in their distributed nature. However, distributed systems rarely overwhelm entrenched systems, no matter how anachronistic they may be. Instead of challenging systems directly, we need to figure out novel ways to construct stories that bypass the normative structures of signaling that currently dominate the landscape.

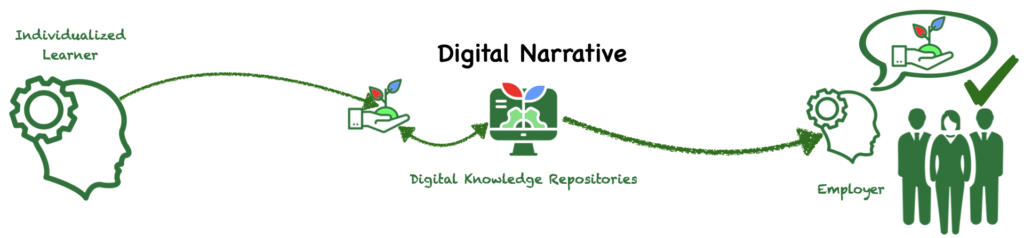

Graduates, even those with specialized degrees such as architecture or engineering, often lack the practical skills required by the employer. When degrees fail to signal specific skills, the learner’s ability to grow and learn independently is critical. Diplomas don’t signal our ability, but authentic work products do. Digital narratives offer us the potential to bypass anachronistic systems through richer mechanisms of storytelling. Labeling becomes less important if it is possible to convey actual artifacts of work.

Alternative systems of credentialing could communicate to the employer the ability of a person to contribute meaningfully to their teams by providing waypoints directing them to authentic artifacts of work. The reason that the current system works so poorly is that systems of education and hiring inevitably reduce the richness of the story of the learner’s journey. Alternative credentialing should not repeat this mistake and try to emulate legacy systems of certification. As an employer, I’m interested in where you are now, how you got there, and whether you have the potential for further growth.

Instead of challenging established systems, alternative credentialing can be used to tell rich stories of growth. These stories can relate the new ways of learning and sharing that the legacy systems miss and can give employers a much clearer picture of the person they are thinking about hiring. Deepening our understanding of ourselves and each other should be the goal of all learning. There is no longer any technical reason we should limit ourselves in the telling of those stories to the world with scraps of paper.