Recently, my friend and futurist, Bryan Alexander posited three scenarios for the coming years of higher education: The Post-Pandemic Campus, Covid Fall, and Toggle Term. In the first scenario the disruptions of this spring rapidly fade into the past with only minor disruptions to future activities. Covid Fall presents a doomsday scenario where both the responses of our institutions and the spread of virus remain beyond control. The third model posits oscillations of viral activity with Covid reappearing spasmodically in time and place and institutions having to react in various ways in response to outbreaks. A savvy planner will hope for the first outcome but will be prepared for the second and third ones. Many universities are beginning to do so. The logistics of running a university or college in this environment are incredibly complex but they only serve the larger goal of learning.

We must therefore not lose sight of the wicked problem of how we might preserve quality (and a measure of equality) within instruction. This is a difficult conversation to have right now because the teaching faculty are deeply submerged in the process of somehow maintaining order out of the chaos that has been produced by the initial wave of the virus.As I have written about before, our instructional choices are bound within a system of constraints ranging from institutional and disciplinary requirements to student expectations. These systemic constraints have by and large not changed. Meeting them, however, has become exponentially harder. Students are already refusing to pay the high cost of education for what they see as a diminished experience. Faculty are struggling to make sense of the realities of the new teaching environments they are now constrained by. Above this hangs the ominous question of whether it is even possible to meet these often-contradictory forces in a pandemic environment.

The answer to this is clearly “yes” but in order to get there we are going to have to do a root-and-branch deconstruction and analysis of how we envision instructional modules and the toolsets that we use to execute them. Some are beginning to discuss classes of shorter duration of either four or five-week duration to make schedules more nimble. This is a good strategy for dealing with oscillating and somewhat unpredictable waves of closures as predicted by Alexander’s Toggle Term scenario, in my opinion the most likely scenario in 2020-2022. However, even with that in place you cannot rule out mid-term disruptions. This strategy also doesn’t address the Covid Fall scenario where the very systems of higher education may be put under existential threat. We do not want to find ourselves there even if the virus proves extremely persistent and severe.

We must consider a set of antifragile pedagogical strategies and approaches within the classroom that are supported by instructional frameworks that help set student expectations. I have argued before that hybrid instruction is the shape of the future. I would add to that argument that the distinction between “in-person” and “online” is increasingly anachronistic. Instead, courses should be identified as having “synchronous” vs. “asynchronous” requirements. Some courses, such as workforce or science labs will require significant synchronous capabilities. These courses have perhaps been the most disrupted by the current crisis.

Moreover, we should not lose sight of the conversational frameworks, as defined by Diana Laurillard that underlie all forms of learning. These frameworks are particularly important to the less-skilled learners that make up a significant proportion of our undergraduate populations. Formative assessment and active learning are essential to their success and deeply impact the qualitative experience of even the most skilled learners. Many of Laurillard’s “conversations” require a measure of synchronous instruction and its capacity for immediate feedback. Synchronous experiences are essential in adding depth to any instructional experience no matter the skill of the learner in question.

How do we continue to create these kinds of rich, and in some cases essential, experiences? We need to consider every aspect of our classes as a set of tools that support both synchronous and asynchronous learning. Most content can be delivered asynchronously in various forms. Applying, analyzing, and putting into practice that content, however, may, in many cases require some form of synchronous interaction between the student and teacher (including librarians, mentors, counselors, tutors, and other support personnel) or between the student and his or her peers in order to achieve meaningful learning experiences.

One of the effects of the pandemic has been to drastically limit the size of gatherings. Serendipitously, meaningful interactions are more likely to occur in small groups rather than in 500-person lecture halls. One strategy would therefore be to assemble a group of tools that would allow institutions to carry out in-person, synchronous instruction in groups of no more than about a dozen people complemented by online delivery of content. Putting a dozen students in a classroom designed for 30+ should allow for social distancing requirements. Hybrid toolsets could be used to stretch the capacities of physical facilities operating at vastly reduced capacity. It also is far easier to develop communities of practice that are closely associated with accelerating learning processes. Having this kind of community will make the learning experience far more antifragile if the course is suddenly moved online.

Nimbleness is in large part conditioned by size. With proper planning and support, learning in smaller chunks coupled with creating meaningful communities of practice will cushion the effects of periodic shocks to our physical environments, while potentially even increasing the meaningfulness of the experience. It’s time to double down on quality, not give up on it. If there is one thing this pandemic has taught us, it is that those communities with stores of human and social capital have proven to be the most resilient. Now is the time for us to look at what makes learning most human and build our educational communities round them. We must never forget that we are in the business of building humans.

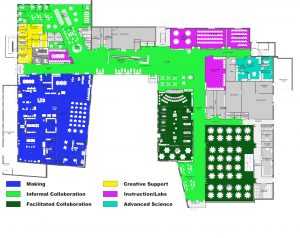

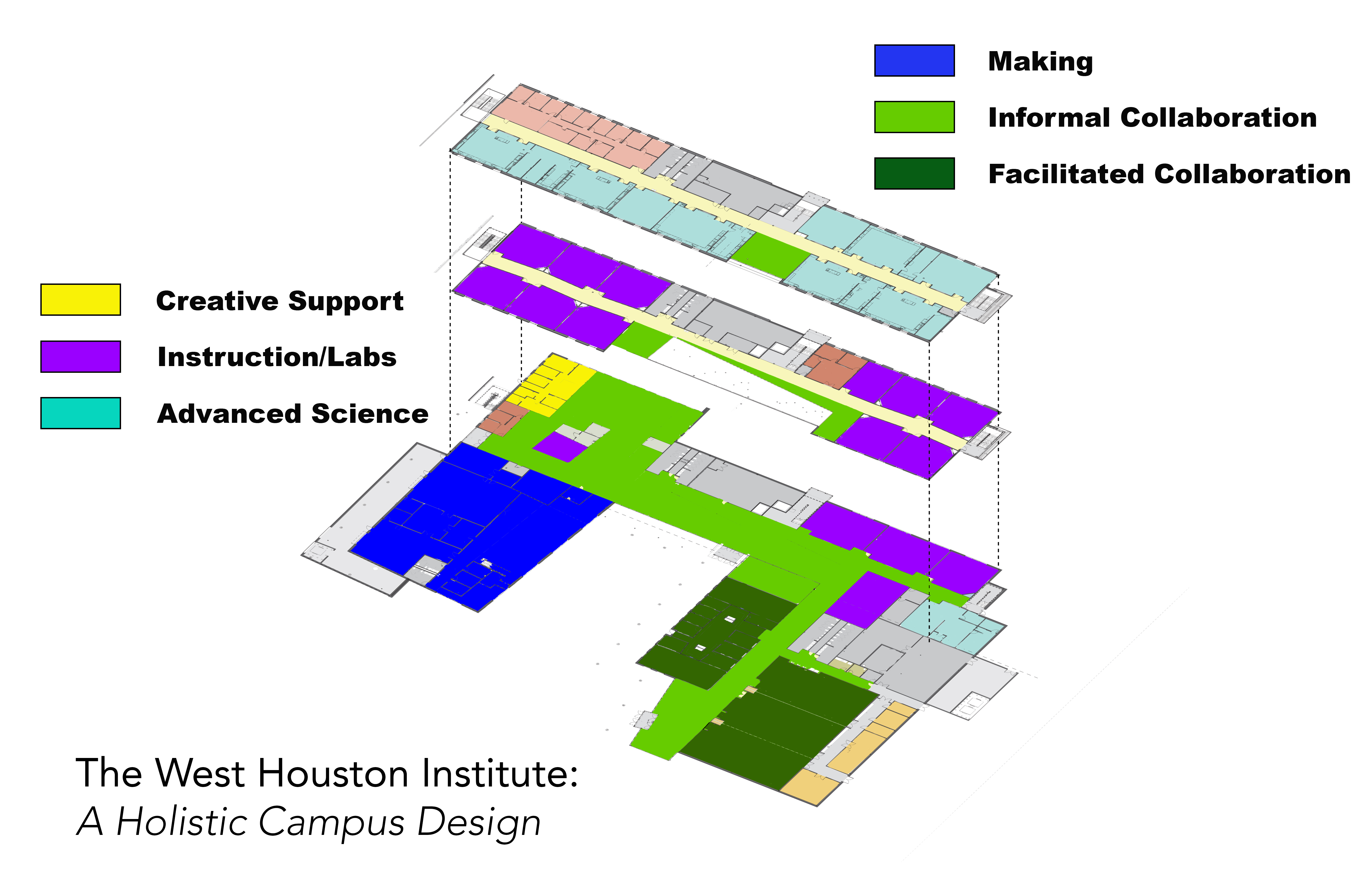

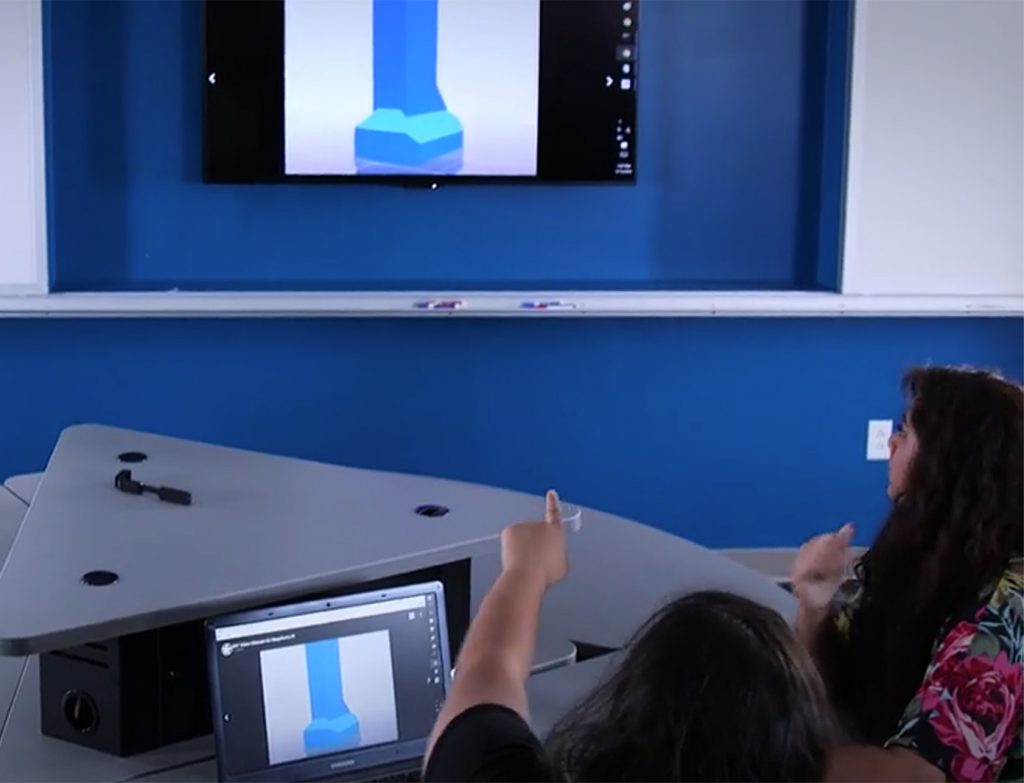

In the spring of 2018, Houston Community College (HCC) opened the West Houston Institute, an innovative campus designed to facilitate design in all of its forms. This 100,000 square foot building incorporates a MakerSpace, a Digital Media Center, experiential science labs, a teaching innovation lab, a conference center, and a wide range of collaborative spaces. Most importantly these spaces were designed to mindfully grow and work together. The WHI is explicitly designed to facilitate the design process and will incorporate important programs developed to facilitate the interdisciplinary aspect of design.

In the spring of 2018, Houston Community College (HCC) opened the West Houston Institute, an innovative campus designed to facilitate design in all of its forms. This 100,000 square foot building incorporates a MakerSpace, a Digital Media Center, experiential science labs, a teaching innovation lab, a conference center, and a wide range of collaborative spaces. Most importantly these spaces were designed to mindfully grow and work together. The WHI is explicitly designed to facilitate the design process and will incorporate important programs developed to facilitate the interdisciplinary aspect of design.