Higher education is struggling with the buffeting that is occurring because of several trends that have been going on for years, if not decades. The release of the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center Final Report on Enrollment, which showed significant enrollment declines across the board, has stimulated many recent conversations on the present and future health of education. Declines were particularly deep among more disadvantaged populations. My good friend Bryan Alexander analyzed these numbers in a recent blog. The ice sheets are clearly moving here and everyone is trying to figure out what’s going to happen next.

Bryan has hosted several conversations that implicitly or explicitly touched on this data on his Future Trends Forum. In the first, the Forum interviewed the authors of Leadership Matters: Confronting the Hard Choices Facing Higher Education, W. Joseph King and Brian C. Mitchell. Although both authors came from the liberal arts college space, they were concerned about the decline in equity reflected in the 2-year college numbers.

As someone who teaches at a 2-year college, I asked whether they thought the problem was partly a cultural one. Over the past century, we have attempted to scale systems originally designed to educate an elite student body. With growing equity following World War II, the implied promise to the middle class was that they too could join that elite if only they could gain admission to their exclusive colleges. Simultaneously, however, we established alternative tiers of higher education, ranging from large public colleges to community colleges that claimed to offer “the same” quality educational experience.

Despite the best efforts of these next level institutions to ape the experiences of their more hallowed cousins, there was a widespread acknowledgement that they could not hope to match the experience of the older, elite institutions. However, what they did import were the systems and cultures of those institutions. Grades, credit hours, and a general elite mentality that “this is the best way to learn” transferred from the Carnegie systems established in the early part of the 20th century. These systems assumed a general acceptance of “academic culture.” “Rigor” came to imply close conformity to those systems of operation.

However, for most of the new students, these systems were alien. At best, they learned how to “play along” just enough to “get a degree” with little appreciation of what that degree really meant other than opening the doors to jobs. At worst, they bounced off and decided that college “was not for me” and settled (often with crushing debt from their incomplete work) for jobs that did not require a degree.

I see a lot of these students in my courses. They do not know how to learn in the prescribed manner. At best, they have learned a work ethic that keeps them in the game but remained focused on the game of school rather than the task of learning. At worst, they quickly lose interest and stop doing the work, failing, or dropping the class. In either case, the work has little meaning to them.

When I asked King and Mitchell about this idea that the college system was disconnected from the realities of most students, they focused on student and teacher preparation. However, I think the problem is far deeper and more systemic than that. What they were talking about was easing the students’ conformity to the game. What I’m suggesting is perhaps we need to look at the game itself.

Most of us are products of this system and it’s no surprise when people miss the elephant in the room. It’s hard to shift paradigms far enough to where we view our own development critically. We are happy with our accomplishments, and deservedly so.

Some college professors may have risen from cultures traditionally excluded by the educational establishment, but they have done so by adopting the vestments of the new culture. Others, myself included, grew up within these systems (my father was a university professor) and take them for granted.

I think that there is a reckoning happening with this cultural disconnect and that this is a big part of the decline in more marginalized higher education students. They rationalize: “What’s the point of going to college? Everyone I know who has tried , has dropped out. And they tell me that the kinds of stuff they are teaching there like Shakespeare, Calculus, history, and government aren’t really very useful for getting ahead in life.”

So what’s the solution? Perhaps if we break it up into smaller chunks and then monetize those chunks so education becomes like currency, that will make it easier for people to get through the process. This was essentially what the Web3 advocates that appeared on The Forum a week later were arguing. Modularized education is the answer, if only we can operationalize it. People can get exposed to the system in smaller chunks and still get credit for the experience.

There is something to recommend in this approach. One challenge my students face is maintaining consistent effort over a long 16-week semester while life happens to them. Again, this is a legacy of the luxuries of industrial education. If you are living on campus or your life revolves exclusively around school, this length makes sense. Most of my students don’t have that luxury. They must deal with jobs, family, and a host of other issues, many of which have been exacerbated by the pandemic. Disruptions are a matter of course. Life gives them short attention spans.

The problem with Web3 is that it applies an economic logic to something that isn’t quantifiable: what does it mean to learn something? Learning is an internalized process. College changed me. It changed how I thought about problems. It changed how I viewed the world. Web3 does nothing to make that easier for my students. The problem isn’t just one of time. More deeply, it’s the aforementioned lack of meaning in the activities that we ask them to pursue. We ask them to “trust us” that this has value. Arbitrarily assigning extrinsic value to something doesn’t give it an intrinsic value, especially for something as ephemeral as learning.

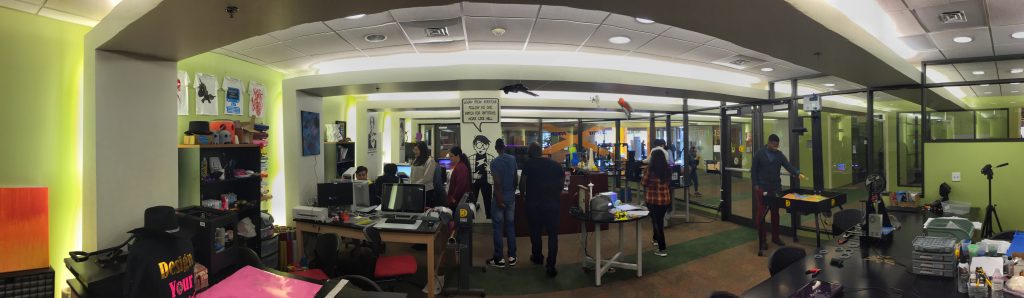

We can use digital tools to create deeper meaning for every learner, whatever their background or capabilities. The problem is that the Industrial Thinking systems that we have constructed around education do not do this for most students. In an article for Current Issues in Education last year, I described how we could set up systems using the same technologies advocated by Web3 proponents. Instead of using the tools to verify “playing the game,” we could use these tools to establish ownership of meaningful artifacts of learning and connect those to a networked community of learning that extends far beyond the traditional boundaries of any institution, or, for that matter, higher education itself.

Ultimately, we are what we build. We build families. We build ourselves. We build our imaginations. Higher education may help us in some of these tasks, but it is itself only a tool to do so. I tell my students that I don’t teach them. They teach themselves. They probably see this as a shirking of my responsibility to them initially. However, a lot of them discover over the course of the semester that what I mean is that I can’t build learning in them. They must do that themselves.

Colleges don’t educate. They provide resources to help their students educate themselves. Until we get away from thinking that says that you have to be good at college to succeed, we’re never going to overcome the meaning gap that we have created for ourselves. Students will continue to be nothing more than cogs in our industrial wheels. It should come as no surprise when more and more of them refuse to allow themselves to be drawn into the grinder.

Philosophically, I wholeheartedly agree with Gardner’s position on this subject. I spent most of graduate school arguing for a cognitive model in international relations and it certainly appeals to my right-brained nature. Furthermore, I know my own learning process has been governed to a large extent by my insatiable curiosity. At the same time, that curiosity attracts me to the possibility of dissecting the learning process in a meaningful way. This is also in part because I continue to be frustrated as a teacher in trying to understand my inability to motivate the vast majority of my students to undertake curiosity-generated, self-directed learning.

Philosophically, I wholeheartedly agree with Gardner’s position on this subject. I spent most of graduate school arguing for a cognitive model in international relations and it certainly appeals to my right-brained nature. Furthermore, I know my own learning process has been governed to a large extent by my insatiable curiosity. At the same time, that curiosity attracts me to the possibility of dissecting the learning process in a meaningful way. This is also in part because I continue to be frustrated as a teacher in trying to understand my inability to motivate the vast majority of my students to undertake curiosity-generated, self-directed learning.