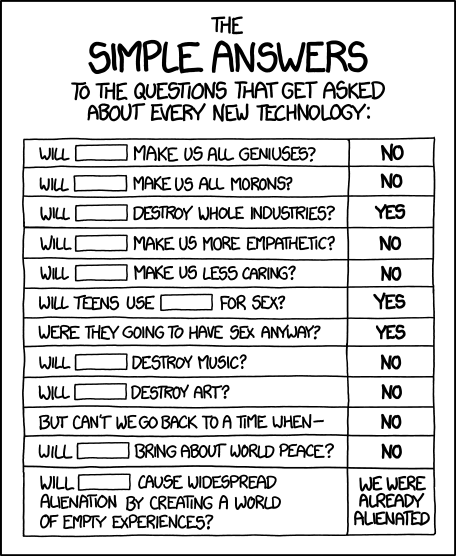

I do believe that we waste countless opportunities to make ourselves, our families, and our societies better because of the phobias we have about technology. We have done this to ourselves through poor design, breeding false mythologies, and the accretion of power to those who would perpetuate them. I continue to believe that technology, especially information technology, offers us unprecedented possibilities for liberation, both on a personal and societal level. There will be dislocations and political challenges, but we can overcome them with a clear-eyed view of the limitations and opportunities that our technologies provide us. Technology is neither moral nor immoral. It is amoral. It is a canvas upon which we paint. The picture we create depends entirely on us. It’s time to pick up the brush. – Discovering Digital Humanity, pp. 15-16.

Source: xkcd 1289

The New York Times is the latest media outlet to see ChatGPT as “technology” undermining education as we understand it. The fear that familiar institutions are being undermined is entirely justified. It is the inevitable consequence of systems of power based on Industrial Age technology being eroded. In recent chats about the technology with colleagues on Bryan Alexander’s Future Trends Forum, I compared ChatGPT and AI to the general alarm that greeted writing in ancient Greece.

And in this instance, you who are the father of letters, from a paternal love of your own children have been led to attribute to them a quality which they cannot have; for this discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality. – Plato, Phaedrus

Plato/Socrates are not wrong here. It is hard to argue with the impact that literacy has had on human augmentation, but there is a lot of nuance to unpack here. We have all met humans who are well read but unwise, because they cannot properly apply the technology of reading/writing to their practice of life. However, as I wrote about in Learn at Your Own Risk, education is mired in a mindset that favors precisely this kind of book-service over knowledge-service.

All too often, the educational establishment (and those who seek to regulate it) equates the “reminiscence” of words with an understanding of those words. What we have witnessed over the history of industrial education has been a gradual scaling of access to writing, first through the mass production of books and then through the mass production of readers.

The reading and repetition of these words has become the bedrock of what we understand as “education.” Even those who teach critical thinking believe that without forcing our students to address this foundation first, we cannot get them to the analysis level of understanding.

This connective tissue of analysis, however, has proven to be a far more elusive (and hard to measure) goal, especially at the lower levels of higher education. I have spent a career trying to teach (and to figure out how to teach) “critical thinking.” It almost always fails on the shoals of trained practice and a lack of meaning in the student experience. I have seen many faculty (myself included) who claim to be teaching critical thinking through writing but who have capitulated to lower expectations.

We have trained most of our students to play along with the education game without really understanding what it was for. This invites them to do things like “cheating” the game because there is no opportunity cost, especially if no one catches them. More pernicious is the tendency to do the “minimum necessary” to pass the class.

ChatGPT threatens this construct. It has the critical thinking skills of a toddler, but we find that hard to distinguish from the efforts of our own students because we have such low expectations from them (derived, in my case, from long, hard experience). It may finally force us to address the loss of meaning many students experience when asked to conform to the existing educational paradigm.

After experimenting with it, I was confident that ChatGPT couldn’t do what I was asking my students to do. However, what I wasn’t confident about was whether I could distinguish between what it did and what they actually produced. It met the “minimum necessary” standard in many aspects of prose (although lacking in the proper citations). ChatGPT’s results weren’t very far off from the kinds of submissions that I routinely get from my students.

This realization didn’t make me toss out my prompts or assessment strategy, however. Instead, I grasped at the opportunity to use ChatGPT to get my students to engage in the critical thinking skills I claim to be teaching them.

My plan for this semester is to have them submit their prompts to ChatGPT as a draft for the first blog and then ask them to critique and build upon the AI’s results. This forces them to augment their approach by using the technology critically.

On a larger scale, however, ChatGPT is yet another chink in the armor of what we’ve been doing in industrial education for over a century. The technological threats to this have been mounting since the early days of the public internet in the 90s. Google search, crowdsourced papers, paper mills, question banks, etc. are all technologies that distributed collective intelligence has enabled. The resources at students’ fingertips have advanced exponentially even as faculty practice has not.

ChatGPT is moving so fast that most of my colleagues don’t even know it exists yet. However, they have been aware of the last two decades of internet-enabled technologies that have threatened our legacy assessment techniques, such as multiple-choice exams and standardized regurgitation essays.

In most cases, this realization has not forced them to re-evaluate their practice. Instead, defense has been the preferred strategy. Efforts to police the use of technology through proctoring and anti-plagiarism software are doomed to failure. If anything, pandemic remote teaching should have taught us that.

As I write in both of my books, the problem here is not one of technology, but rather of adapting ourselves, our practices, and systems to new realities. And, to take this further, there are tremendous opportunities resulting from these adaptations. We need real thinkers at all levels to tackle the complex problems of today and tomorrow.

Technology can connect us and augment us if we design and use it to do so. Applied properly, ChatGPT can form part of a suite of tools to make us better and more critical thinkers.

A friend of mine asked me the other day what I thought the purpose of society should be. My response was: we have a responsibility to our children to make the world better than when we came into it and societies should strive toward that goal. I then referred him to the Platonic concept of the philosopher-king. Technology has the possibility of making us all kings. Education has a duty to make us all philosophers.