Up to this point in our discussion of transparency, we have been talking about things that are very real technologies. Today, I want to take a small step into near term reality based on current tools.

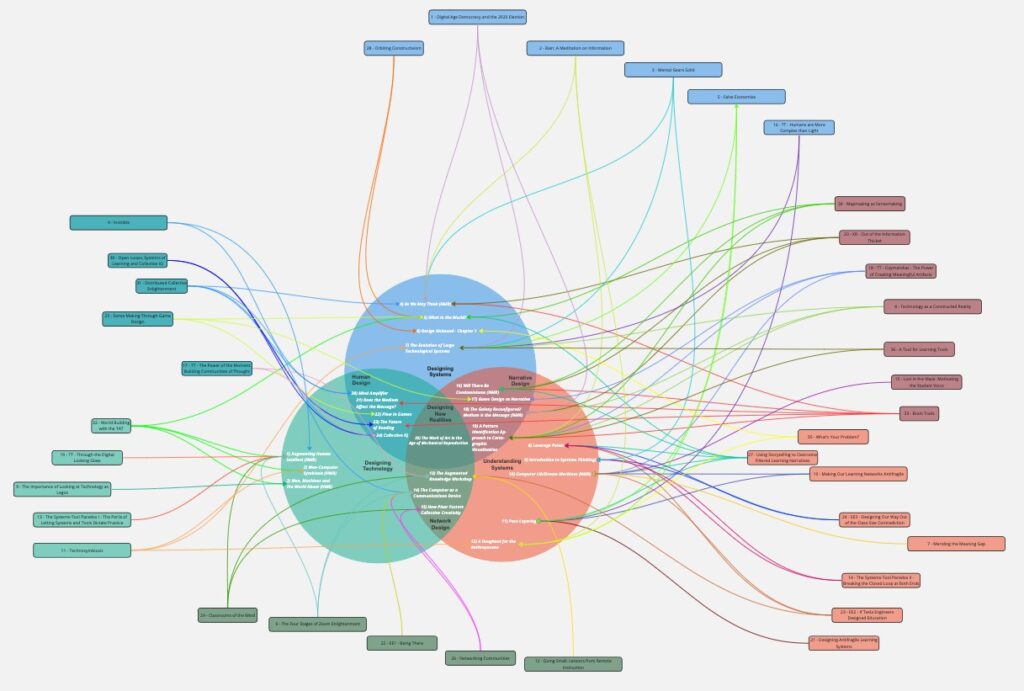

So far, we proposed opening the doors of information locked away in proprietary boxes, putting that information into perspective through concept mapping, and constructing linked canvases of ideas through layered concept mapping. This week, I want to fuse these ideas with the technology of the moment, Generative AI.

Information processing is a labor-intensive process. Whether we’re creating documents for large companies, or just trying to keep a handle on our own thought processes. I have filing cabinets of semi-sorted paper, hard disk drives of data, and thousands of pages of my writing.

Since the days of HyperCard, one of my chief struggles in life has been making logical sense out of all the information I collect. I have found very few shortcuts and have massive data forests to contend with.

Even more frustrating is when my brain tells me I need a particular piece of data and I can no longer find it. I have tried various tools over the years to organize that data going all the way back to HyperCard, but maintaining those tools was a labor-intensive process. Even after I put the data into the tool, it quickly became dated and sometimes inaccessible.

When I write, I know I am getting knowledge from a vast range of sources. Sometimes those are explicit, such as my current recollection of Vannevar Bush’s Memex,. Often, however, years of research shape my writing in subtle ways. Sometimes I can figure out those connections with a great deal of work, but sometimes it’s just too hard to backtrack my thinking that far back. Even if I can, it’s a major effort to locate the original source.

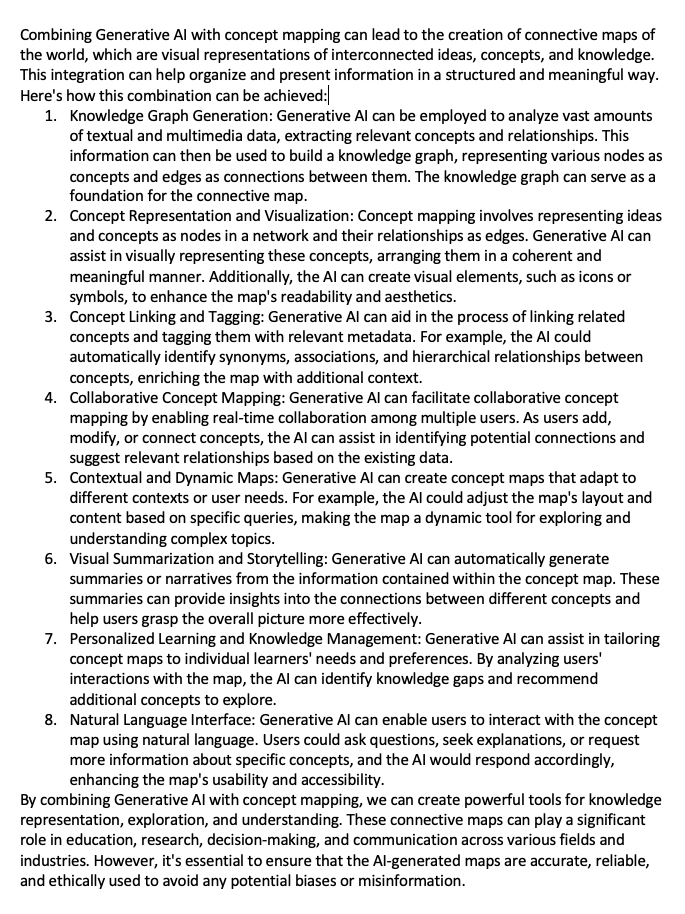

Generative AI is making a vast array of connections as it creates documents. It does this by scraping data from a range of sources. Like the bread crumbs on the web, the connections to these sources are hidden. This practice has caused considerable controversy among content creators. I asked ChatGPT “How can we combine Generative AI with concept mapping to create connective maps of the world?” This was its response in text form:

ChatGPT has produced some interesting responses, but I want to explore where it’s getting its information from and how we might connect those ideas into a more comprehensive approach to mapping ideas.

This should be possible. Generative AI is an augmented connection device. However, like the web, ChatGPT hides those connections.

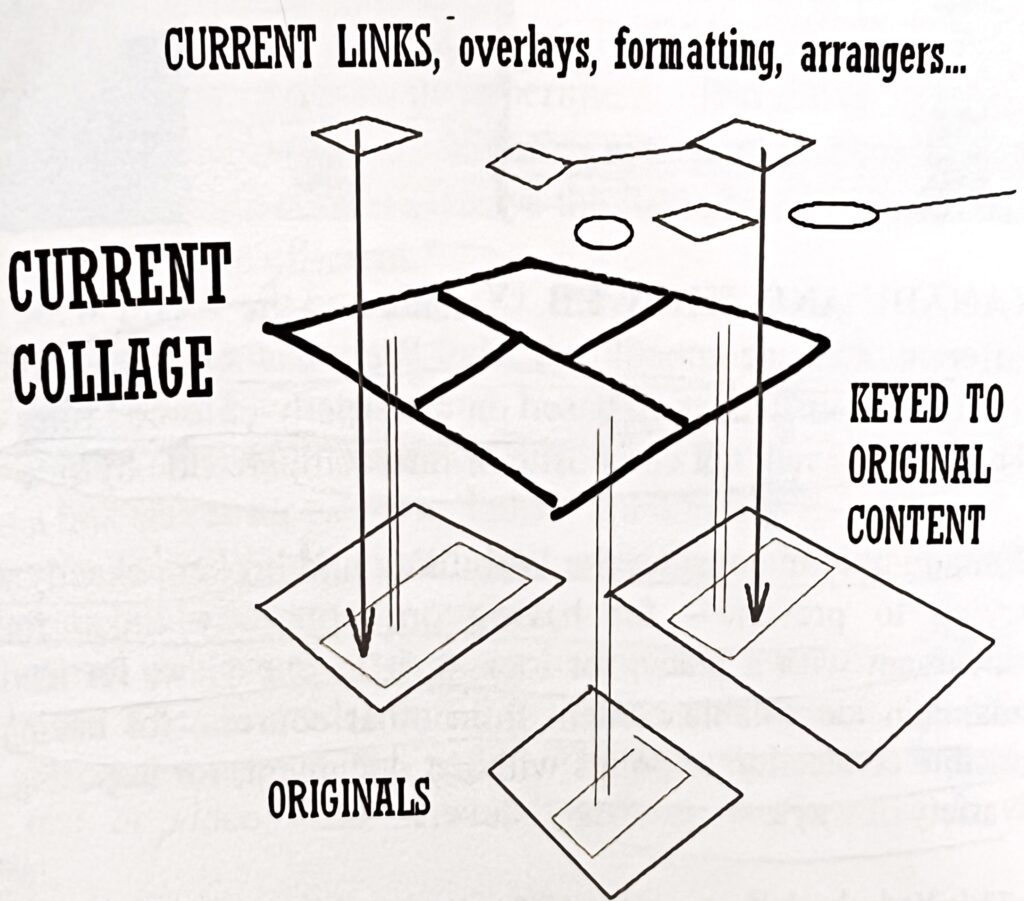

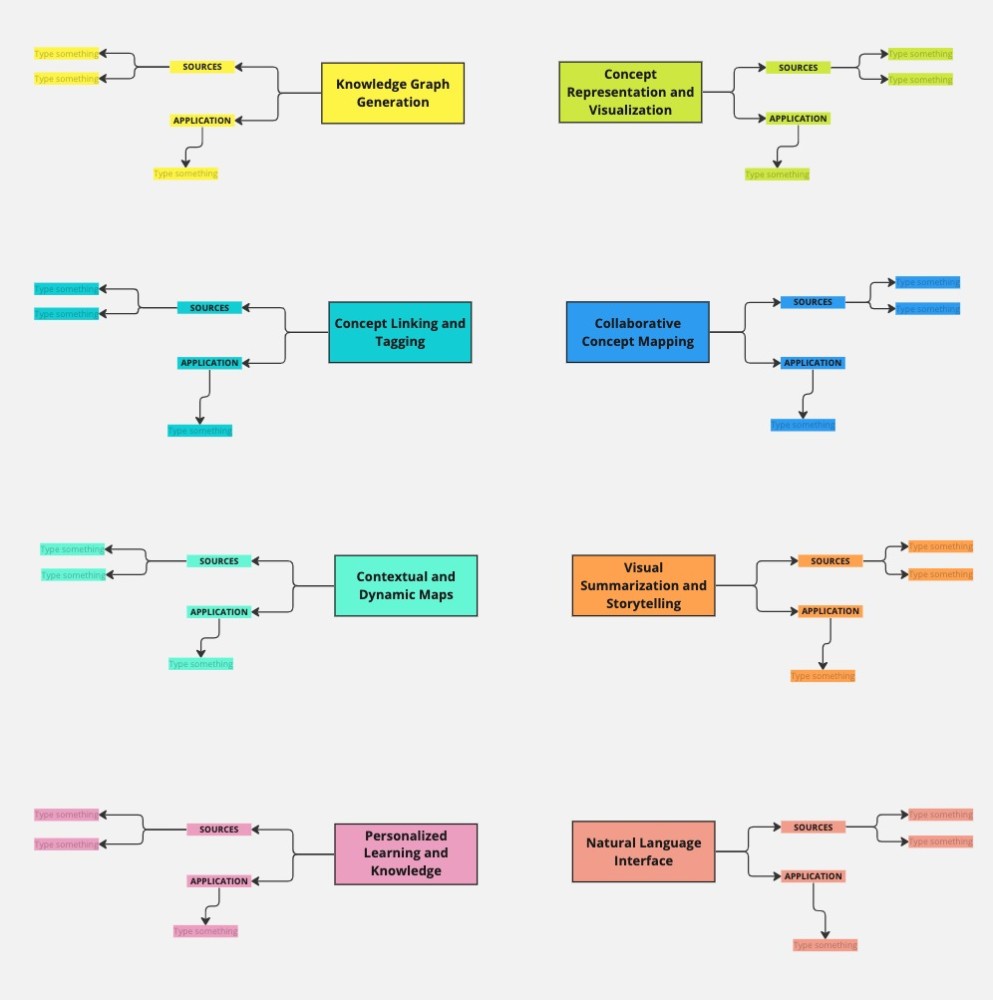

If we made Generative AI transparent, it could also be an augmented perspective device. I took those ChatGPT results and plotted them on a Miro concept map.

This map represents an iterative step. There is nothing new being added to the map compared to the ChatGPT response. I Generative AI could generate this kind of map. A further iteration would add sources and applications as well as suggest connections between items on the list. Right now, humans (like me) must do this part.

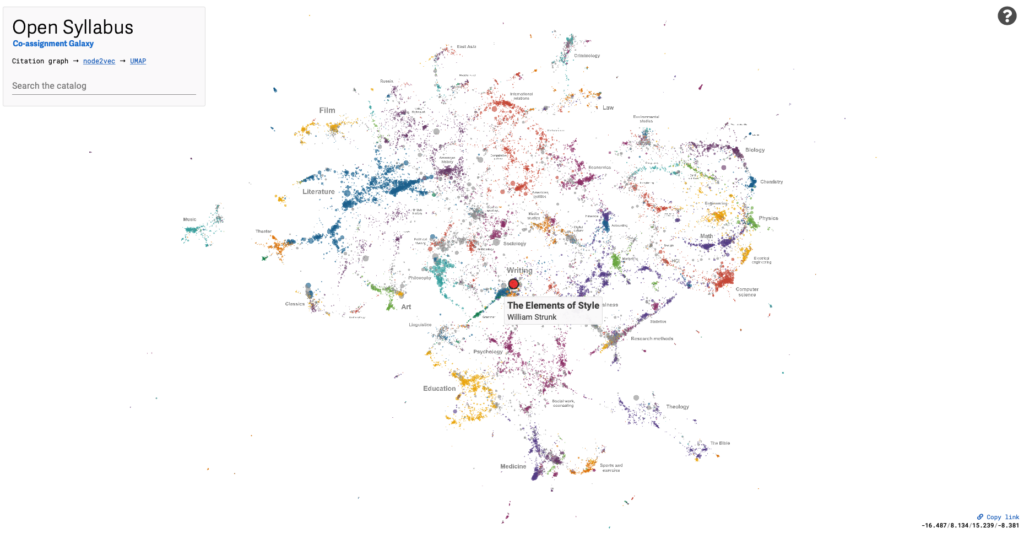

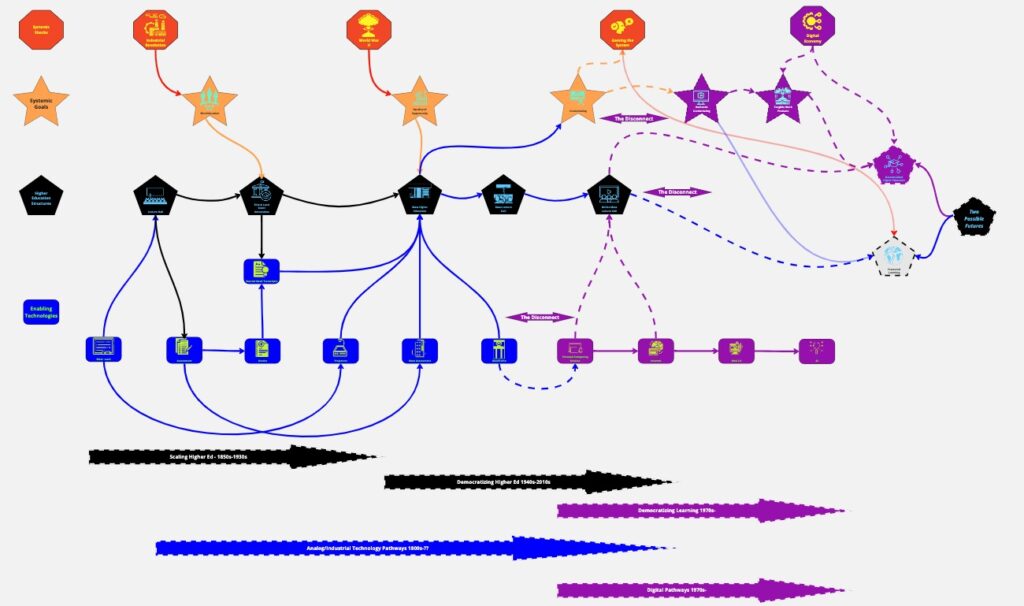

Coming at this from complex to simple patterns, one of the more interesting tools I found in recent years is the Open Syllabus Project. It plots a heat map of all the readings from open college syllabi. It forms a knowledge heatmap of what we teach in higher education through the materials on our collective syllabi.

There’s a lot about this diagram that is automated, but it still requires a fair amount of labor to set up and maintain. However, I could see this kind of tool being fused with AI to create automatic heatmaps from any collection of data.

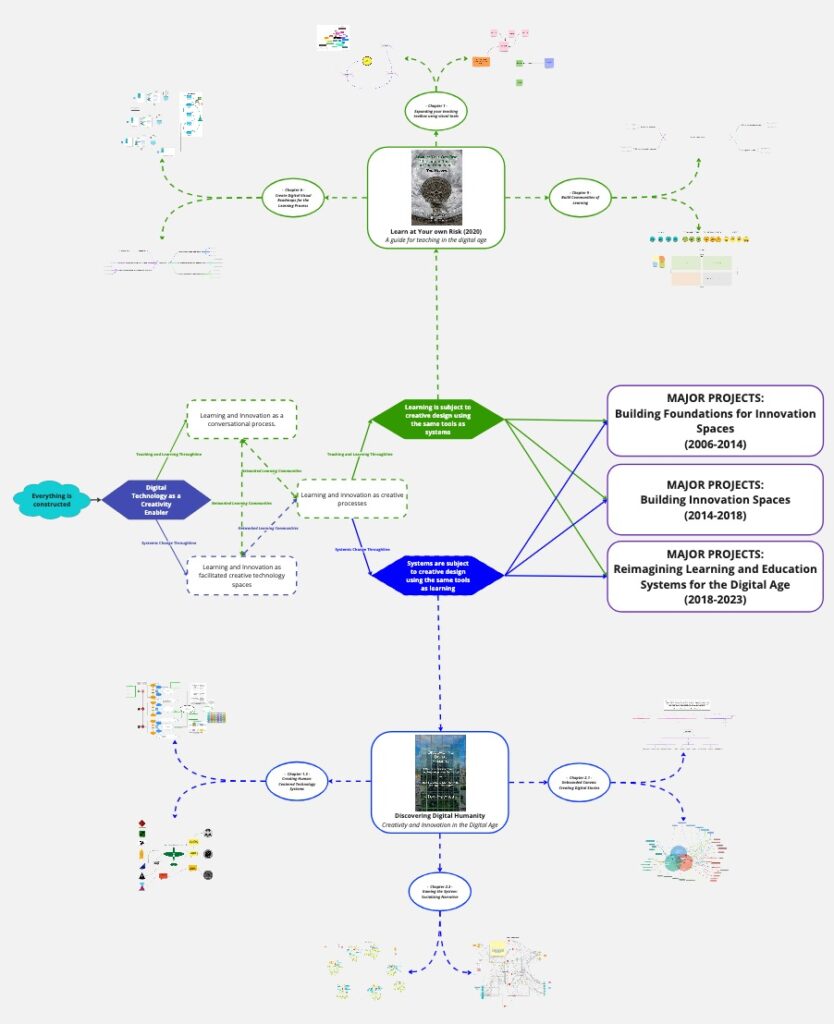

I can imagine a host of uses for this kind of tool. As you may recall from the previous blog, I created a connected set of ideas and projects for my Miro resume.

This was a tedious and labor-intensive process, even though I had all the data I needed from IdeaSpaces. Computation excels at replacing tedious labor.

These are just three examples of what is possible with AI tools that automatically aggregate datasets and propose linkages. Consider for a moment just how much of today’s professional work is spent doing just that.

I used to work at an architecture firm. Most new architects spend huge amounts of time creating what are called construction documents. These connect the design to the materials, furniture, fittings, and equipment necessary to build the building.

This is tedious work. It is also a task that consists almost entirely of making connections between various bits of data. Generative AI is made for these are the kinds of tasks.

This would disrupt the architectural practice as it exists today. Creating construction documents is a central part of the process for breaking in new architects. Demand for junior architects would decrease.

However, this is also an opportunity for firms and schools to up their game and bring architects into practice at a higher level than is currently the case. Also, someone is going to have to manage this AI process.

On a personal level, I would love a Large Language Model AI that would look at my writing and suggest where I’m getting my ideas from or to provide suggestions for additional exploration of adjacent ideas.

This would automate that frustration I described earlier. Probably 90% of the resources I have accumulated over the years have been digitized, either by me or by some other entity. Connecting them is the real challenge.

This kind of tool would also tell me if someone else has explored the same territory. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been writing and thinking “surely, someone has thought of this before.”

Concept maps are an ideal tool for surfacing the connections that the AI finds. Instead of providing a list of sources or materials, an AI coupled with a concept mapping tool like Miro could give us a connective heat map that is both live and evolving. Humans could then focus on creativity and novelty.

This brings us full circle back to the blog from the beginning of this series. Imagine an AI that creates a concept map or a heat map of all the connections, while constantly pulling from live data. We could use this to fine-tune the AIs. Visualization also creates opportunities for oversight to mitigate bias or other kinds of intellectual corruption from occurring.

We could use these kinds of maps for regulatory oversight to spot areas of mistakes or deliberate gaming of the system. A generative system, coupled with a visual output, could create these kinds of documents automatically, making compliance with government oversight much less onerous and labor-intensive than today.

If we can get past the alarmist rhetoric and look at the possibilities for human augmentation that these tools provide, we can unlock stores of overlooked or hidden information to improve our societies, to advance science and knowledge, and to help us overcome the very real challenges we face as a species today.

Information is at the core of everything. Learning has always been the killer app for the human species. It’s what gave us key advantages in our revolutionary struggle. The explosion of information over the last 40 years or more has made comprehending what we’re seeing more difficult, not easier. This is because we optimized technology to distribute information, not connections.

It is time to take the next step and connect that store of information to our human abilities to make connections and find patterns. For that, we need to think differently about the tools at hand, and the tools we should prioritize building. Perspective creates wisdom. Wisdom is in short supply these days.