ChatGPT is not the first digital age disruption to challenge our systems of industrial education. I can identify at least three systemic shocks that have occurred since the proliferation of the internet in the 1990s: Web 2.0, remote teaching, and now AI. These were not assaults on learning, they were assaults on the systems of education. Learning has been under assault for much longer than that.

Fifty years ago, Ivan Illich recognized the gulf between learning and systems of education when he wrote:

The pupil is thereby “schooled” to confuse teaching with learning, grade advancement with education, a diploma with competence, and fluency with the ability to say something new. His imagination is “schooled” to accept service in place of value. (Ivan Illich, Deschooling Society, 1970)

Illich understood that the purposes of educational systems were diverging from the practice of learning even then. Those systems of education have persisted and solidified since he wrote Deschooling Society. Since then, the gulf between substance and performance has grown.

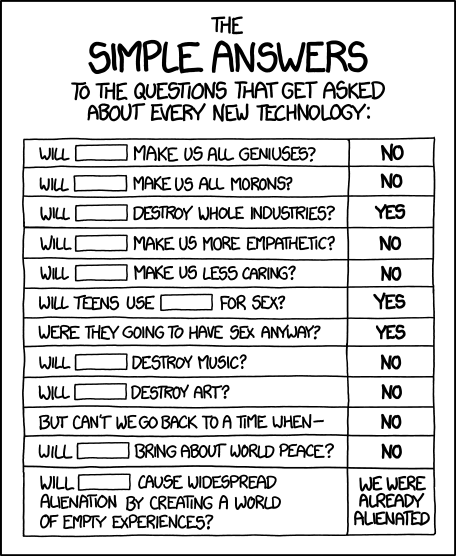

Web 2.0 posed a challenge to the systems of education that had emerged as we automated learning and grades became the core of the system. Web 2.0 technologies made it easy for anyone to contribute to the conversation on the internet.

With Web 2.0 tools, communities could form around just about anything, including gaming the systems of education. If these systems had been focused on the goal of learning, its members would have perceived Web 2.0 as an opportunity to grow communities, not a threat.

Unsurprisingly, educational systems focused on protecting systems of education, not the goal of learning. That purpose, as Illich observed, had been long relegated to secondary status. In Thinking in Systems, Donella Meadows refers to this as “seeking the wrong goal:”

System behavior is particularly sensitive to the goals of feedback loops. If the goals – the indicators of satisfaction of the rules – are defined inaccurately or incompletely, the system may obediently work to produce a result that is not really intended or wanted.

[The Way Out is to] Specify indicators and goals that reflect the real welfare of the system. Be especially careful not to confuse effort with result or you will end up with a system that is producing effort, not result. (p. 140)

The system reacted to Web 2.0 by implementing technologies such as anti-plagiarism and proctoring software to “protect the integrity of grades.” There was little movement in the paradigmatic logic of the higher levels of the system. The system did not explore the “way out”.

The alternative approach would have been to create communities of practice using these new tools. While communities of practice would not have eliminated the threat of cheating, they would have helped move the focus toward learning, not gaming the system. The very Web 2.0 technology that made the cheating possible could be turned into a facilitator of learning.

This was not the path taken. Only a few institutions considered the paradigmatic shifts necessary to create true communities of practice using the new technology.

Another shock was the sudden need for remote teaching during the pandemic. Most institutions failed to use the maturation of video conferencing software mated with Web 2.0 platforms to explore what these new modes of interaction could do to augment practice, both during and after the pandemic.

Instead, we’ve seen a rush back to “normality” as pandemic restrictions have eased. During the pandemic, we saw the effects of building walls and hunkering down on both learning outcomes and the overall quality of the experience of learning in the absence of physical classrooms. We are still seeing the after effects of our collective choices in the face of this crisis in terms of diminished enrollment, particularly in on-campus environments.

Remote teaching was a different kind of shock than Web 2.0 (or AI). It demanded a lot of improvisation as the crisis hit. Some very interesting approaches emerged and were tested under difficult circumstances.

Some of these innovations have persisted and have within them the seeds for further growth. In many institutions, online-on-a-schedule and other kinds of blended learning experiences that don’t threaten the core logic of the systempersist.

AI is the latest chapter in this story. The AI “Crisis” is more like Web 2.0 in its evolutionary nature than remote teaching, but slow fuses often lead to bigger explosions.

The fuse that was lit by Web 2.0 didn’t explode until confronted with the requirements of remote teaching. Even then, the focus was more on damage control than evolving systems capable of withstanding future explosions.

Educational systems are already beginning to hunker down in the face of this challenge. However, this strategy is showing signs of decay. Students increasingly see through the fiction of learning and are seeking alternatives to traditional instruction.

It is no surprise that educational systems are inflexible. Any practice based on perceived legitimacy is going to be resistant to change because it questions past legitimacy. Nicholas Taleb points this out in Antifragile:

Education, in the sense of the formation of character, personality, and acquisition of true knowledge, likes disorder; label-driven education and educators abhor disorder. Some things break because of error, others don’t. Some theories fall apart, not others. Innovation is precisely something that gains from uncertainty: and some people sit around waiting for uncertainty and using it as raw material, just like our ancestral hunters. – Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (Kindle Edition), p. 550.

Education’s reliance on past legitimacy for much of its value generates its own unique contribution to Clayton Christiansen’s innovator’s dilemma, which argues that you have to be willing to threaten your existing product every few years in the service of creating innovation.

Few companies are capable of this. Even fewer educational institutions are desperate enough to engage in it. Legislative or accreditation restrictions may also constrain their ability to pivot.

Teachers are at the thin edge of the wedge here. They are being asked to defend practices that are no longer viable. It is also profoundly human of them to resist change. It is easier to retreat to the methods used to teach you than it is to strike out onto unfamiliar ground.

It’s scary to reinvent yourself under the best of circumstances. That reinvention becomes almost impossible in the face of institutional and structural resistance. Couple that with a systemic crisis and it’s no wonder so many institutions are diving for their bunkers in the face of AI.

And so, we find ourselves in the third shock. We have institutions that are rigid, working on borrowed time, and are not very antifragile. AI presents us with a slow-boiling crisis. Its eventual impact remains difficult to predict.

Educational systems should not look to students to drive change. We have perverted their preferences in deference to the old system so much, it’s clear that most of them have almost no understanding of how the system shapes their preferences. Their only choice is to opt-in or opt-out of the game. More and more are opting out.

Healthy systems, per Donella Meadows, “aim to enhance total systems properties, such as creativity, stability, diversity, resilience, and sustainability — whether they are easily measured or not.” (Meadows, Dancing with Systems). Does this describe the current state of education?

Based on the education system’s reactions to Web 2.0 and remote teaching, reactions to AI are likely to resemble those taken to counter Web 2.0. We are already seeing “AI Detection” software, including one from the OpenAI Group itself. Building walls is not a good solution to any challenge, especially one where the residents (students) can simply choose never to enter the walled garden.