Originally published on April 6, 2021 at: https://shapingedu.asu.edu/blog/systems-tool-paradox-part-ii-breaking-closed-loop-both-ends

Part I – The Perils of Letting Systems and Tools Dictate Practice

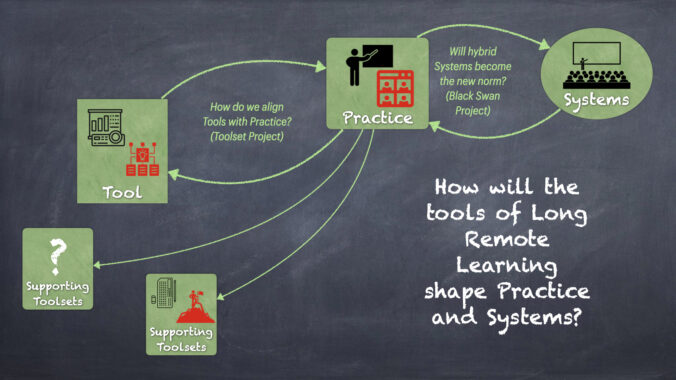

Yesterday, we discussed how tools and systems become entangled in closed loops that tend to preserve systemic preferences about teaching and learning, even when they no longer meet the needs of the vast majority of learners. The problem with both systems and tools is that we usually accept them uncritically and attempt to adapt practice to be more learner-centric. However, as I discuss in my recent book, Learn at Your Own Risk (ATBOSH, 2020), there are hard limits to how much you can adjust practice and how effective those adjustments will be on learners accustomed to the existing paradigms. To address this challenge we need to attack the problem from both ends and analyze both systems and tools to look for opportunities to create new and more productive learning paradigms.

It is hard to untangle the impact of tools and systems on each other. At the systemic level we need to envision what a post-pandemic, antifragile system of instruction should look like. My own interests on this level center around rethinking how tools have the potential to reshape what we consider to be a “class,” how it’s delivered, and how the current structure has impeded holistic, interdisciplinary approaches to learning that will be critical in preparing our students to address the global challenges of climate change and automation.

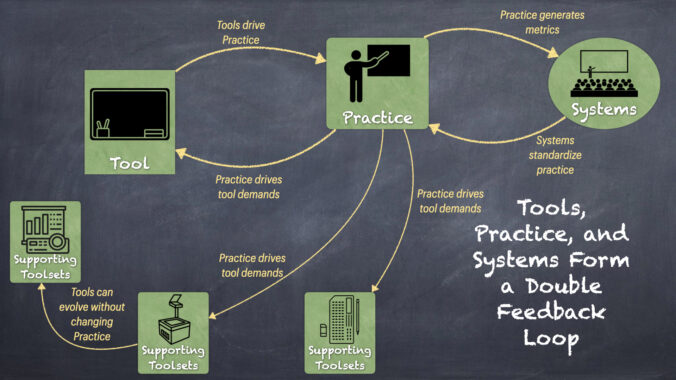

Parallel to our exploration of systemic-level change, we must also understand how our tools drive the systems that they are a part of, and vice versa. We’ll explore how tools drive instruction in more depth in a series of upcoming hackathons to expand the Teaching Toolset Triangle Project. The goal of this project is to provide a mechanism for both faculty and administrators to explore creative uses of the tools we use to facilitate learning. The Toolset Triangle is designed to allow us to hack paradigms and use our collective knowledge and experience to demand tools that fulfill the ends of individualized, empowered learning.

Tool vendors, from learning space design to learning management systems to textbooks, are all driven by catering to the preferences of the markets they support. If those markets demand tools based on archaic paradigms, that is what those providers will provide. A few years ago I worked at an architectural firm trying to help them design learning spaces for the future. However, what quickly became apparent was that the kinds of questions I insisted on asking made their clients uncomfortable. Instead of educating their clients, the firm decided the better strategy, from a business perspective, was to give the clients what they wanted. What the clients wanted was largely driven by industrial models and so even the most “innovative” learning spaces never really questioned those paradigms.

This is a serious problem. As was pointed out in yesterday’s blog, the tools drive the systems but, more importantly, are themselves driven by the logic of systems and the practices that they seek to rationalize. The logic of education is not driven by the needs of the learner. The logic of education is driven by the educational systems that have evolved since the 19th Century.

If you challenge higher education to explain the ends we are seeking for our students, it is virtually impossible to come up with a consensus. That is because reality often has little to do with aspiration and that is in large part because that aspiration is so ill-defined. What does it mean to learn? How do we measure that? We almost never confront that question honestly. As Diana Laurillard says in Teaching as a Design Science: “We cannot challenge the technology to serve the needs of education until we know what we want from it. We have to articulate what it means to teach well, what the principles of designing good teaching are, and how these will enable learners to learn. Until then, we risk continuing to be technology-led.” (p. 4) At the tool level, therefore, we need to re-establish the primacy of the task – learning – when it comes to designing ecosystems of tools that are meant to support learning. This is what the Teaching Toolset Triangle Project seeks to do.

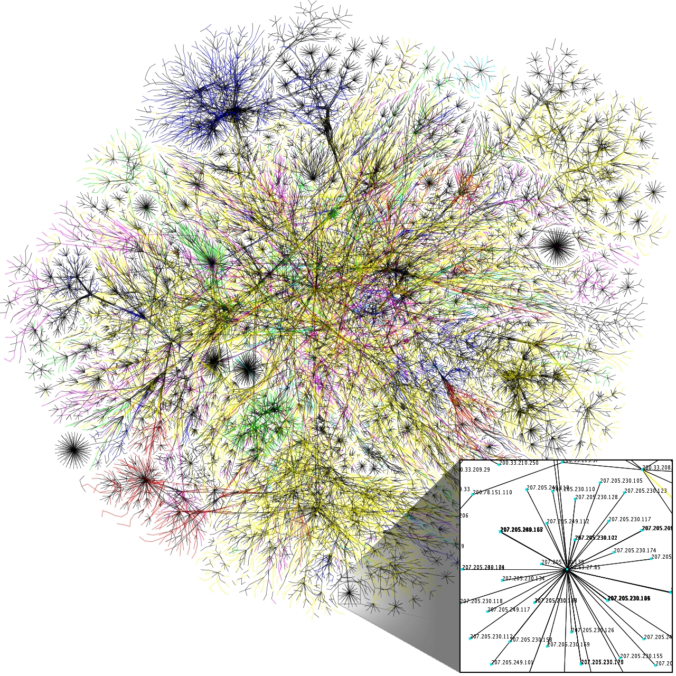

When the blackboard entered the scene in the mid-1800s, there really weren’t many other learning tools outside of pen and paper. The Digital Age has seen a vast proliferation of tools and we’re about to be hit with a second wave of opportunities through the gradual adoption of XR technologies. Having gone through the first wave as an administrator, I saw that time and time again tools were adopted in a completely haphazard manner and that the vast majority had little or no impact on pedagogical outcomes as a result. That was largely because tools were adopted without understanding their pedagogical impact. Often, technology was purchased by technology groups or the IT department without any clear purpose in mind, much less working from any kind of deep understanding of how learning works.

One of the lessons of Remote Teaching is that this needs to change. All too often I saw faculty struggling with technology that was designed for corporate meetings, not effective classroom instruction. As we return to physical environments, we need to mindfully reintegrate in-person instruction with some of the affordances of digital instruction we discovered when we were physically separated from our students. This summer the Toolset Triangle will host a series of hackathons centered on three tool groups (physical, virtual, and XR) where participants will hack them to explore how they could reshape our pedagogy and how our pedagogy can shape the tools we demand to facilitate learning. The goal is to produce a handbook describing uses for tools as well as tools we should be demanding based on the hackathons.

Systems are reshaped slowly even in times of crisis. Remote teaching has provided us with an opportunity to engage in new conversations. ShapingEDU facilitates conversations. Conversations form the basis for learning. Systemic change is a product of scaled learning. Join us in the conversation and move the world.