(Originally Published on nmc.org May 2012)

Learning analytics presents some serious dilemmas for the academic community. It is tempting to think that our advancing capabilities in data collection and processing make understanding the learning process an achievable goal. However, because we have never really managed to define what successful learning looks like, figuring out what and how to measure, much less how to use that data to change what we do, poses some major challenges. My experience teaching this semester as well my intellectual effort in imagining a learning analytics platform have shown me that there are at least three major, interconnected hurdles to overcome before we can proceed: definition, doctrine, and culture.

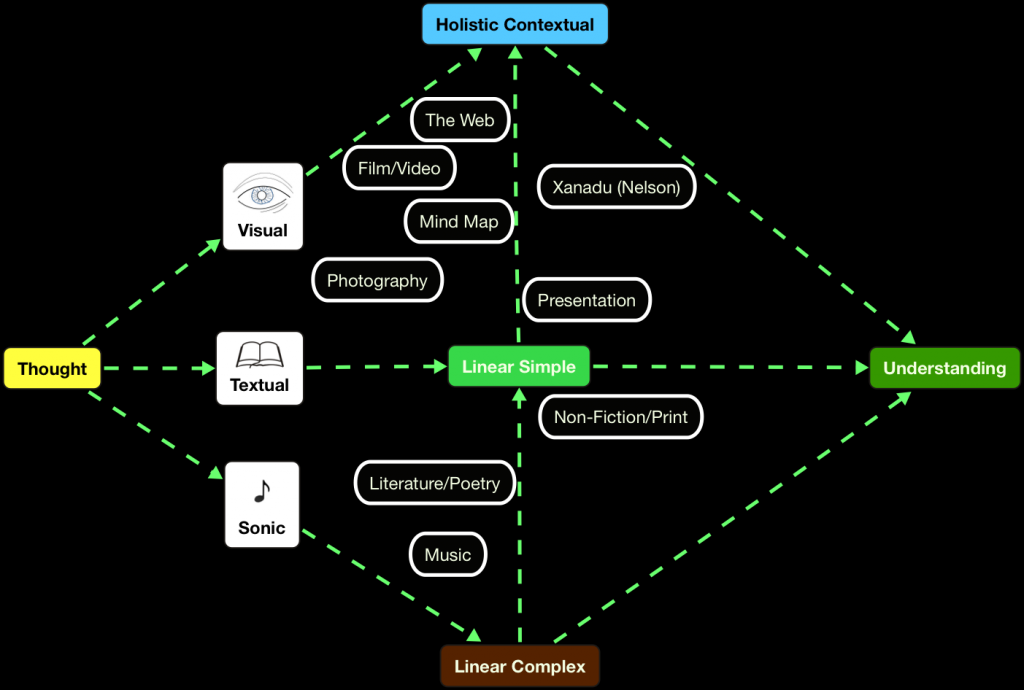

Before we can go into the technicalities of developing a learning analytics system, we need to come to some definitional agreement over the ultimate purpose of higher education. Is it to teach a basic canon of knowledge? Is it to teach critical thinking skills? Or, is critical thinking not going far enough? Do we need to teach what Michael Wesch calls “knowledge-ability?”

Our only hope of developing meaningful variables to measure learning is by clearly defining our educational goals. Making meaningful comparisons across multiple classes, and even more so across disciplines, depends on coming to some sort of consensus around these often-divisive issues.

In addition to being clear about definitions we also need to address the doctrinal dichotomy over whether learning is essentially a cognitive process or behavioral process. A behaviorist would argue that learning could, in theory, be broken down into a set of discrete steps or benchmarks that lead to success. This approach would lend itself quite well to the quantitative aspects that big data would seem to offer us. Its misuse is also, unfortunately, the basis for much of the standardized testing environment that we have seen inflicted on the K-12 environment.

There is a powerful cognitive counter-argument, recently expressed by Gardner Campbell in addressing George Siemens’ LAK12 MOOC. The argument here is that learning is essentially impossible to quantify because it is a voyage of discovery with ill-defined markers along the way. The job of a teacher is to facilitate this voyage among his or her students. How do you measure the learning process using this approach? Can we develop a tool to measure curiosity, for instance? Furthermore, quantification risks taking education even further over to the dark side of standardized formulas for “learning.”

Philosophically, I wholeheartedly agree with Gardner’s position on this subject. I spent most of graduate school arguing for a cognitive model in international relations and it certainly appeals to my right-brained nature. Furthermore, I know my own learning process has been governed to a large extent by my insatiable curiosity. At the same time, that curiosity attracts me to the possibility of dissecting the learning process in a meaningful way. This is also in part because I continue to be frustrated as a teacher in trying to understand my inability to motivate the vast majority of my students to undertake curiosity-generated, self-directed learning.

Philosophically, I wholeheartedly agree with Gardner’s position on this subject. I spent most of graduate school arguing for a cognitive model in international relations and it certainly appeals to my right-brained nature. Furthermore, I know my own learning process has been governed to a large extent by my insatiable curiosity. At the same time, that curiosity attracts me to the possibility of dissecting the learning process in a meaningful way. This is also in part because I continue to be frustrated as a teacher in trying to understand my inability to motivate the vast majority of my students to undertake curiosity-generated, self-directed learning.

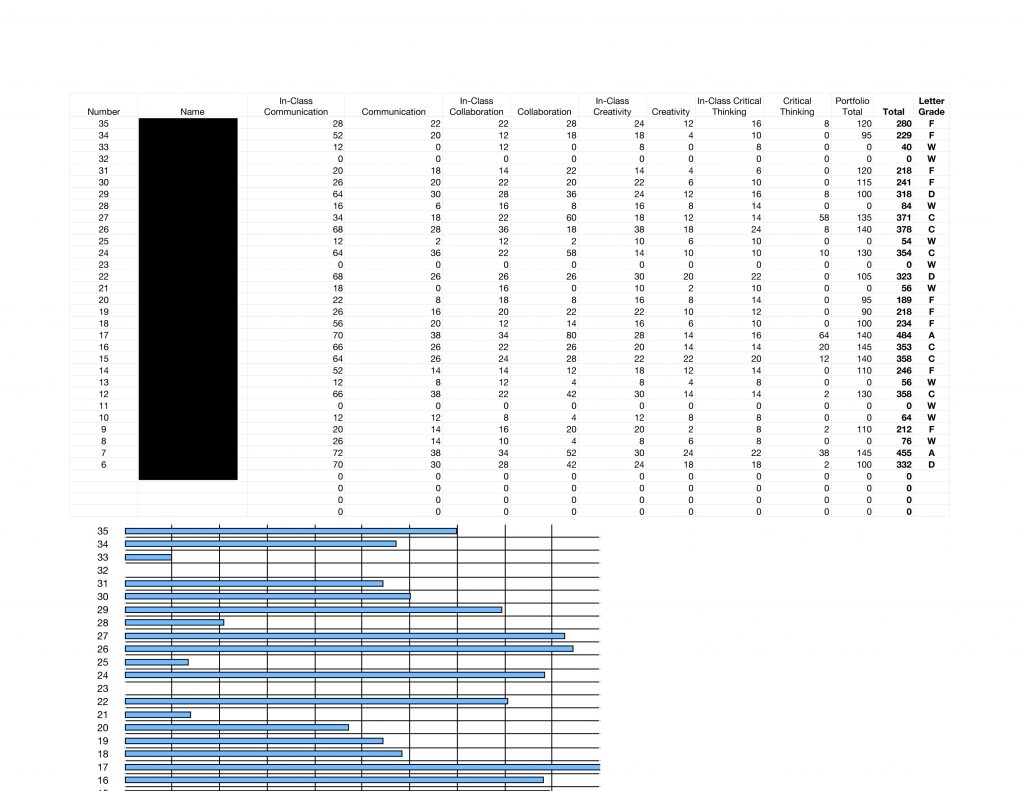

Even if we can get past the definitional and cognitive/behaviorist issue, there is yet a third hurdle and that is cultural/institutional inertia. My recently concluded semester teaching a government class is a good example of the perils of getting too far ahead of the curve or outside the norms of traditional teaching approaches. As usual, I started the semester with high hopes that trying something new would lead to greater success for my students. I refocused the syllabus around a skills-based approach and attempted to give my students the freedom to explore areas of interest to them. I also tried some novel technological solutions such as incorporating Google+ and Google Docs into the workflow with the goal being to mentally take students out of the classroom as much as possible. At the same time I wanted to give them exposure to technical tools that they will need master in future work environments.

This experience left me disillusioned over my ability to break through cultural norms even in my own class, much less convincing other faculty to attempt similar efforts in their own classes. From the perspective of a faculty member, breaking down my assignments into their skill components was hard work. As a teacher with a built-in motivation (my interest in learning analytics) and an unusual propensity to take risks in class, I was able to convince myself to see this through. My experience with other faculty is that they are often understandably risk-averse and resistant to change. In other words, I’m not sure what I attempted was scalable even if it could be proven effective.

Furthermore, the changes required a significant paradigm shift on the part of both my students and myself. The students resisted, for the most part without complaint or feedback, my attempt to shift the paradigm of their learning experience. I ultimately gave up on trying to impress the significance of this approach on them. For the most part they were only concerned with the bottom line of what their final grade would be. Furthermore, freedom to explore did not agree with many of them as the class had a high failure rate. This was because many of them used their freedom to avoid doing the minimum amount of work necessary for success in the class.

The bottom line is that both students and faculty will resist this kind of cultural shift. It’s hard work and it involves an intellectual paradigm shift many won’t be willing to undertake. It’s hard to imagine a meaningful learning analytics project without a significant re-evaluation of teaching and learning being a part of the process.

To reinforce the point, I recently attended an iPad workshop put on by Apple. In it, they demonstrated how the new iBooks app, coupled with iBooks Author, could be used to create self-tests and flashcards for the readings. When I pointed out to the presenter that this was a classic McLuhanesque mistake and, furthermore perpetuated an outmoded form of teaching (rote memorization), he pointed out to me that, while he agreed with me, this was what most of the audience wanted to see pitched. Unfortunately, I could not argue with him on that point.

I am down but not out when it comes to learning analytics and the related mission of reinventing teaching and learning to meet the realities of the modern world. While I don’t see it as a magic bullet for student success, I continue to hope that it will provide critical insights to enable us to find a pathway to achieving those ideals. It also offers me an irresistible intellectual puzzle with the hope of making a real difference in the lives of our students.

As Yeats said, “Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire.” We clearly need more matches and less water. At the same time we can’t overlook the theoretical, doctrinal, and cultural barriers that will impede meaningful measurement of the learning process, much less allow us to reshape the process based on the data produced. However, we ignore the coming seismic shifts in teaching and learning at our peril. There is still a lot of discussion and hard thinking to be done here. In order to square this circle we have to figure out how to be disruptors while preserving the essence of what makes education such a special experience.